Gerald Murnane

Something for the Pain: A Memoir of the Turf

Gerald Murnanewas born in Melbourne in 1939 and spent part of his childhood in country Victoria. He has been a primary teacher, an editor, and a university lecturer. His debut novel, Tamarisk Row , was followed by nine other works of fiction, the most recent of which is A Million Windows . He has also published a collection of non-fiction pieces, Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs . Murnane has won the Patrick White Award, the Melbourne Prize for Literature, and the Adelaide

Festival Award for Innovation. He lives in western Victoria.

1. Something for the Pain

MACHINERY AND TECHNOLOGY have always intimidated me. I did not dare to use a motor mower until I was in my fifties with sons old enough to help me start it. I bought a mobile phone fifteen years ago and have carried it ever since in the boot of my car. I make a call occasionally but have never even learned to store numbers in my machine. My previous car had a facility for playing audio tapes, and I succeeded in mastering it. However, the car that I bought four years ago plays only compact discs. I have a few discs that I listen to occasionally at home but not enough to warrant my struggling with the thing in my dashboard. I can use the radio in my car but, because I live in a remote district, I can pick up only a few stations and their programs fail to interest me. Luckily, I can pick up the station that broadcasts horse races from all over Australia and even, sometimes, from New Zealand. I still call the station 3UZ, although it acquired a fancy new name some years ago.

Only a few years ago, the Herald Sun published every day the fields and riders and form for every race meeting covered by the Victorian TAB. Nowadays, only a few meetings appear in print. No doubt the details of all the other meetings are available on some or another website, but a man who can’t use the CD player in his car is hardly likely to be able to use computers. And so, when I’m driving on some lonely road in the far west of Victoria and I switch on my car radio, the names of the horses in the race being described are likely to be names that I’ve never seen in print. The course where the race is being run is likely to be far away in the vast part of Australia where I’ve never been. What, then, do I see in mind while I’m listening to a rapidly delivered report of the changing positions of horses unknown to me in a place I’ve seen only on maps?

Writing has for me at least one advantage over speaking. While I’m writing, I pause often to make sure that the words I’m about to set down are truly accurate. I may have told someone in conversation that I often see in mind, while I’m driving alone, a field of horses approaching a winning post at Gunnedah or Rockhampton or Northam. But I’m not about to write that I see any such thing. I ought rather to write that a radio broadcast of a horse race brings to my mind a swarm of vague, blurred images, a few being images of horses with jockeys up but most having no resemblance to horses or jockeys. The images are accompanied by feelings, some easy to report — such as my willing one or another horse to win — and others difficult indeed to describe.

Perhaps if I were a horseman, I would more easily call to mind the horses themselves while I listen to race broadcasts. I might even imagine the race from the viewpoint of a jockey with a straining, pounding horse beneath him. The fact is, though, that I’ve never sat astride a horse, let alone urged it into a gallop or even a canter. During all the countless hours that I’ve spent on racecourses, I’ve never really looked at a horse. When I recall some of the famous horses that have raced in front of me — Tulloch, Tobin Bronze, Vain, Kingston Town, and the like — I see in mind no images of bays or browns or chestnuts or whatever, with distinctive heads or conformation. Instead, I might recall, for example, the finish of the first race that Tulloch won in Melbourne, on Caulfield Cup Day, 1956, or the newspaper pictures of his elderly owner during the weeks when the old fool dithered over Tulloch’s running in the 1957 Melbourne Cup. I would not fail to see an image of Tulloch’s racing colours — Red-and-white striped jacket, black sleeves and cap. I would see also the features of the jockey who often rode Tulloch, Neville Sellwood, the same man who deliberately stopped Tulloch from winning the 1960 Melbourne Cup, just as he stopped the favourite, Yeman, from winning the 1958 Cup. (I can’t prove these claims, but for me they are facts of history.) As well as seeing these things in mind, I would feel again the feelings forever bound up with those remembered images. I might even become again for a moment the troubled young man that I was when Tulloch was racing. But I don’t want to go there just now. I’m supposed to be writing about my present self, alone in my car on an empty road and hearing a report of a field of unknown horses on some faraway racecourse.

Many people seem to believe that what passes through their minds is a sort of mental film: a replay of things that have already happened or of things that might happen in the future. Perhaps some people do have films running through their minds, but most of the sequences in my mind are more like cartoons or comic strips or surreal paintings. Often, the sounds of a race broadcast will cause me to see in mind what I saw during the first years when I heard such sounds. Those were the years from 1944 to 1948, when I lived in a weatherboard cottage in Neale Street, Bendigo. I would have liked, during those years, to sit in the kitchen with my father of a Saturday afternoon and to listen with him to the radio broadcasts of races from Flemington, Caulfield, Moonee Valley, or Mentone, but both my parents discouraged me from doing so. If they sensed already that their eldest child was on the way to becoming obsessed with horse racing, then they were absolutely correct. If they sensed that he would one day gamble recklessly, crazily, on horses as his father was often apt to gamble, then they were wrong. And if they thought that their banning him from listening to race broadcasts would take away his interest in horse racing, then they were likewise wrong.

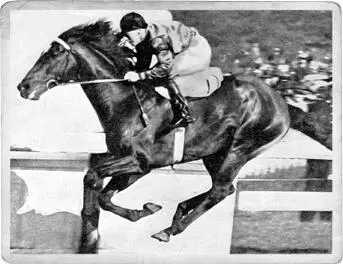

Bendigo was a quiet place in the mid-1940s. Few motor vehicles passed along Neale Street or nearby McIvor Road. Even halfway down the backyard, among my pretend-landscapes of farms and roads and townships each with a racecourse on its outskirts — even there I could hear as much as I needed to hear of the sounds from the mantel radio in the kitchen. What I heard were not distinctive words but vocal sounds: a chant or a recitative that began quietly, progressed evenly, rose to a climax, and then subsided again. I had never seen a horse race, but I saw every Wednesday the centre pages of the Sporting Globe . That thriving publication was always printed on pink newsprint, which made the dim reproductions of black-and-white photographs even more grey and grainy. The centre pages of the Globe , as everyone called it, were filled with results of the Melbourne race meeting of the previous Saturday. Around the margins were detailed statistics, and on either side of the central gutter were the pictures that I pored over: two pictures for every race, one of the field at the home turn and the other of the same field at the winning post.

The pictures, as I wrote above, were grey and grainy. As well, several of the racecourses of Melbourne were so arranged that the winning post was overshadowed by the grandstands from mid-afternoon onwards. As a result, anyone wanting to see in the Globe the images of the horses themselves had to strain to distinguish them from the murky background. This never troubled me. I learned all that I wanted to learn from the names of the horses, which were clearly printed in uppercase letters in the upper half of each illustration. Each name was enclosed in a boldly outlined rectangle, and from some part of the lower margin of each rectangle a shape like a curved stalactite led down to the head of the horse denoted by the name in the rectangle.

Читать дальше