This memoir tells the true story of my childhood, based on my memories, my interviews with family and friends, and my research. Some names have been changed.

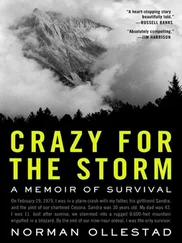

CRAZY FOR THE STORM

NORMAN OLLESTAD

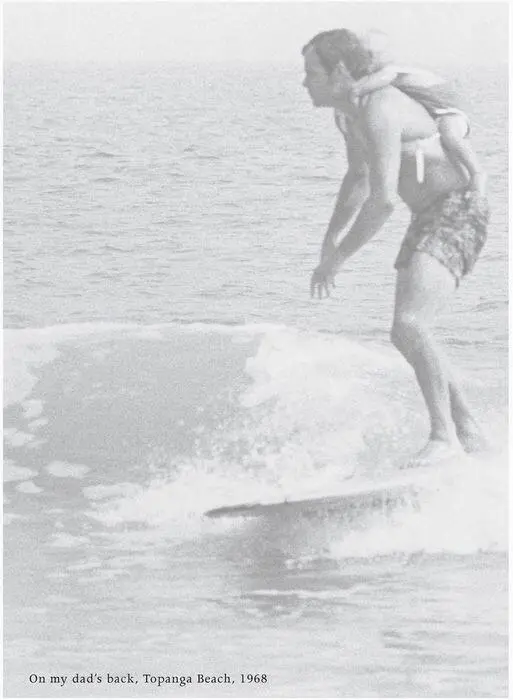

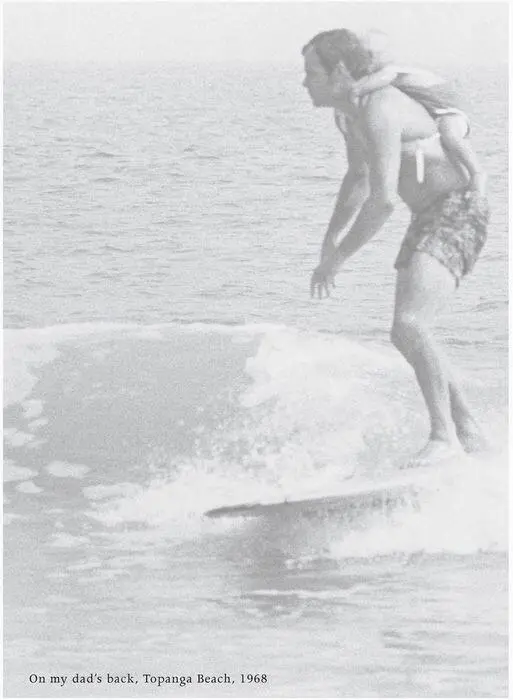

My father craved the weightless glide. He chased hurricanes and blizzards to touch the bliss of riding mighty waves and deep powder snow. An insatiable spirit, he was crazy for the storm. And it saved my life. This book is for my father and for my son.

I am harnessed in a canvas papoose strapped to my dad’s back. It’s my first birthday. I peer over his shoulder as we glide the sea. Sun glare and blue ripple together. The surfboard rail engraves the arcing wave and spits of sunflecked ocean tumble over his toes. I can fly.

Cover Page

Author Note This memoir tells the true story of my childhood, based on my memories, my interviews with family and friends, and my research. Some names have been changed.

Title Page CRAZY FOR THE STORM NORMAN OLLESTAD

Dedication My father craved the weightless glide. He chased hurricanes and blizzards to touch the bliss of riding mighty waves and deep powder snow. An insatiable spirit, he was crazy for the storm. And it saved my life. This book is for my father and for my son.

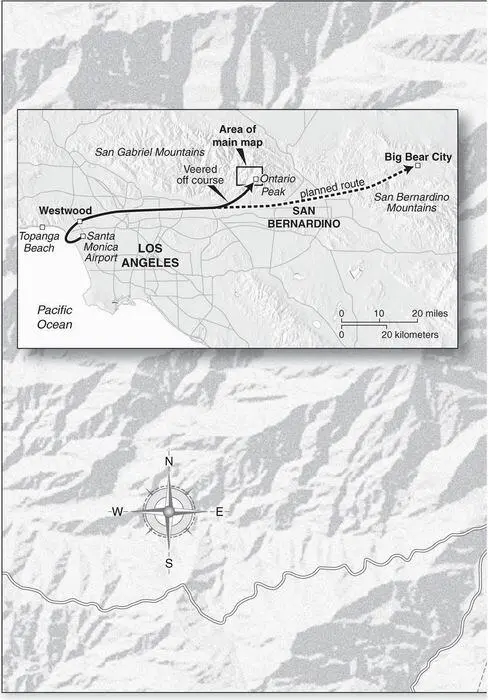

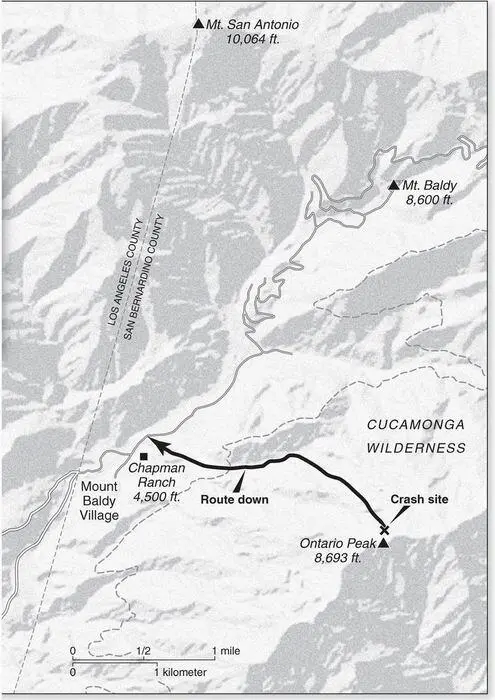

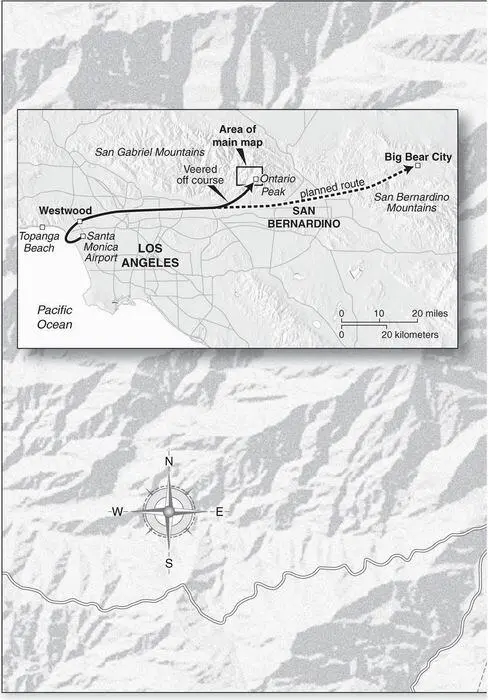

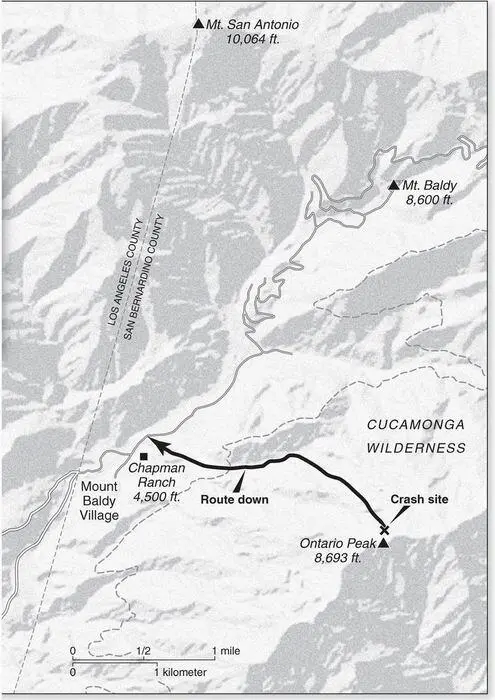

Map

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

CHAPTER 37

CHAPTER 38

CHAPTER 39

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Photographic Inserts

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

FEBRUARY 19, 1979. At seven that morning my dad, his girlfriend Sandra and I took off from Santa Monica Airport headed for the mountains of Big Bear. I had won the Southern California Slalom Skiing Championship the day before and that afternoon we drove back to Santa Monica for my hockey game. To avoid another round-trip in the car my dad had chartered a plane back to Big Bear so that I could collect my trophy and train with the ski team. My dad was forty-three. Sandra was thirty. I was eleven.

The Cessna 172 lifted and banked over Venice Beach then climbed over a cluster of buildings in Westwood and headed east. I sat in the front, headphones and all, next to pilot Rob Arnold. Rob fingered the knobs along the instrument panel that curved toward the cockpit’s ceiling. Intermittently, he rolled a large vertical dial next to his knee, the trim wheel, and the plane rocked like a seesaw before leveling off. Out the windshield, way in the distance, a dome of gray clouds covered the San Bernardino Mountains, the tops alone poking through. It was flat desert all around the cluster of peaks, and the peaks stood out of the desert as high as 10,000 feet.

I was feeling especially daring because I had just won the slalom championship and I thought about the big chutes carved into those peaks—concave slides, dropping from the top of the peaks down the faces of the mountains like deep wrinkles. I wondered if they were skiable .

Behind Rob sat my dad. He read the sports section and whistled a Willie Nelson tune that I’d heard him play on his guitar many times. I craned around to see behind my seat. Sandra was brushing out her silky dark brown hair. She’s dressed kind of fancy, I thought.

How long, Dad? I said.

He peered over the top of the newspaper.

About thirty minutes, Boy Wonder, he said. We might get a look at your championship run as we come around Mount Baldy.

Then he stuffed an apple in his mouth and folded the newspaper into a rectangle. He would fold the Racing Form the same way, watermelon dripping off his chin on one of those late August days down at the Del Mar track where the surf meets the turf . We’d leave Malibu early in the morning and drive sixty miles south to ride a few peelers off the point at Swami’s, named for the ashram crowning the headland. If there was a long lull in the waves Dad would fold his legs up on his board and sit lotus, pretending to meditate, embarrassing me in front of the other surfers. Around noon we’d head to Solana Beach, which was across the Coast Highway from the track. We’d hide our boards under the small wood bridge because they wouldn’t fit inside Dad’s ’56 Porsche, then we’d cross the highway and railroad tracks to watch the horses get saddled. When they came into the walking ring Dad would throw me on his shoulders and hand up a fistful of peanuts for lunch. Pick a horse, Boy Wonder, he’d say. Without hesitation he’d bet my horse to win. Once a long shot named Scooby Doo won by a nose and Dad gave me a hundred-dollar bill to spend however I wanted.

The mountaintops appeared higher than the plane. I stretched my neck to see over the plane’s dashboard, clasping the oversized headphones. As we approached the foothills I heard Burbank Control pass our plane onto Pomona Control. Pilot Rob told Pomona that he preferred not to go above 7,500 feet because of low freezing levels. Then a private plane radioed in, warning against flying into the Big Bear area without the proper instruments.

Did you copy that? said the control tower.

Roger, said pilot Rob.

The nose of the plane pierced the first tier of the once distant storm. A gray mist enveloped us. The cabin felt compressed with noise and we jiggled and lurched. Rob put both hands on the steering wheel, shaped like a giant W. There was no way we were going to get to see my championship run through these clouds, I thought. Not even the slopes of Baldy where my dad and I had snagged a couple great powder days last year.

Then the gravity of the other pilot’s warning interrupted my daydream.

I looked back at my dad. He gobbled down the apple core, smacking his lips with satisfaction. His sparkling blue eyes and hearty smile calmed my anxiety about the warning. His face beamed with pride for me. Winning that championship was evidence that all our hard work had finally paid off, that anything is possible, like Dad always said.

Over his shoulder a crooked limb flashed by the window. A tree? Way up here? No way. Then the world turned back to gray. It was just a trick of light.

Dad studied me. His gaze seemed to suspend us as if we didn’t need the plane—two winged men cruising a blue sky. I was about to ask how much longer it would be.

Читать дальше