I said, It is the kind of thing I’d expect you to take my word for.

“Gurion,” he said, “I—”

Or would’ve expected.

“But—”

No, I said, you’re right. When you’re right you’re right. I said, But just because you’re right doesn’t mean you know the truth.

“Stop for a second. Listen, okay? Even if I did believe you… Even if I did accept your girlfriend was Jewish, I’m saying no one else in the community would. And that is a good thing, isn’t it? We practice Judaism, yes? Not Gurionism. This is a good thing.”

I know, I said.

“You don’t seem to like it, though.”

I have to go home, I said, and write scripture.

“No commentary, no matter how thoughtful,” he said, “will be powerful enough to persuade the Jewish community that you have the authority to convert this girl, Gurion. Not when your motives are so clearly personal.”

And I thought: You hear “Jew” when I say Israelite, and “commentary” when I say “scripture.” You see Esther’s husband while looking at June’s.

My personal motives? I said to the Rabbi.

“Where are you going? Please sit back down. Stay for dinner.”

I said, I’ll write scripture and you’ll know the truth.

“You’re unhappy with me, Gurion. You’re in distress. Don’t run out of here. Stick around for dinner. There’s no need to run. We’re talking,” he said. “We’ve got more to say. We’ve got more to study.”

You’ve been a good teacher, I said.

I went home.

to Canrovsky’s

There was a new, semi-literate bomb in front of the WELCOME mat on our stoop. It was supposed to say “Welcome to Carnovsky’s” but the vandal switched around the r and n.

I knew it was supposed to be Carnovsky because Carnovsky is a fictional character made up by the fictional character Nathan Zuckerman, who is the protagonist in many books by Philip Roth. A lot of Jews in Roth’s first few books about Zuckerman think that Carnovsky is a self-hating Jew and that because Carnovsky is a self-hating Jew, Zuckerman is a self-hating Jew.

But any smart Israelite who ever read Roth’s books knows that Carnovsky is not a self-hating Jew, which negates the assertion that Zuckerman (for creating Carnovsky) and Roth (for creating Zuckerman who creates Carnovsky) are self-hating Jews.

So to say that my father was a Carnovsky was to say that my father was falsely accused of being a self-hating Jew, and that was a nice thing to say — it was what I said.

But no one would vandalize the stoop of a man he wanted to be nice to.

So it was easy to conclude that the vandal misunderstood what a Carnovsky was — that the vandal, like so many of Roth’s fictional Jews, was not that smart, and missed Roth’s point, and thought Carnovsky was a self-hating Jew, and thus thought my father was a self-hating Jew.

And that’s what I concluded at first, and for a second I almost felt a little good, thinking, The enemies of my family are such stupid bancers, they not only mistake Carnovsky for a self-hating Jew, but they can’t even spell his name.

Except then I started wondering if the transposition of the r and n wasn’t an accident. I.e., wasn’t it possible that the vandal knew Carnovsky wasn’t a self-hating Jew and had switched around the letters on purpose — like Eliyahu did the o and y of typos in his joke about the Cage manual — in order to ironize the bomb? Maybe the message was: “Look, the only kind of guy who’d claim that Judah Maccabee is, like Carnovsky, falsely accused of being a self-hating Jew can’t even spell Carnovsky .”

It was possible. And not only that, but it made the bomb a lot more effective: The enemies of my family who were stupid enough to believe Carnovsky was a self-hating Jew would forgive the misspelling out of admiration toward the vandal for his having bombed the Maccabeean stoop; the enemies of my family who didn’t know who Carnovsky was wouldn’t know the name was misspelled and would admire the vandal without need of forgiving the misspelling; the enemies of my family who were smart enough to know that Carnovsky wasn’t a self-hating Jew would not only admire the vandal for bombing the stoop, but admire the cleverness behind his misspelling; and my family itself… we’d stand there staring at our enemy’s message, thinking about it, trying not to admire its cleverness and failing. I would, that is. No. I wouldn’t. I thought: I won’t.

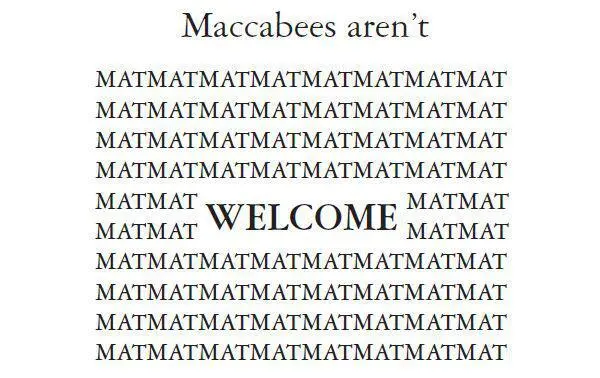

I pulled the mat down to cover to Canrovsky’s and the stoop looked like:

I tried adjusting the mat so that it covered both lines of grafitti, but the mat wasn’t large enough, so I took out my Darker and got on my knees.

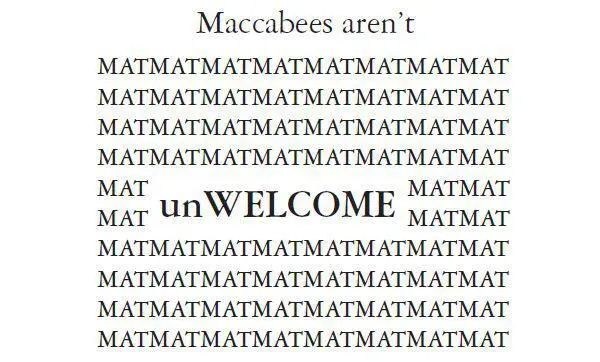

When I finished editing, the stoop looked like:

It was the best I could do. As long as the vandal kept coming around while I was at Aptakisic — and why shouldn’t he? he kept getting away with it — I wouldn’t be able to blind him. Not unless I ditched school. I wasn’t going to ditch school. School was where June was.

I thought: Is she thinking of you right now, too?

And I thought: She might be.

I thought: You need to go inside and write scripture.

I thought: Your scripture will outlast the bombs of the vandals.

I pulled my frontdoor keys from my spypocket and found rolled-up commentary wedged in the ring. The paper was pink and printed double-sided in Lucida Calligraphy, the favorite font of Esther Salt and soon-to-be brides everywhere:

Dear Gurion,

I beg you be sensible and sensitive like you used to. Do you really think I would spend thirty minutes waiting for you in the cold of the mid-to-late autumn chill on my stoop without a coat if I didn’t want you to do a kind thing for me by giving me your jacket so you could prove that you are still the sweetest boy to me who will always be my first and only true love no matter what?

Oh Dear Gurion,

Don’t you understand that I was angry for all these many and varying weeks we have spent away from each other in our respective lonely and cold solitudes since that sad and fateful Shabbos on which you delivered me your heartbreaking poem? How could you not see that when I broke up with you it was not to break up with you but to let you know that I wanted you to come see me more and at least try to kiss me at least once because we were together for so long and you never even tried to hug me or even ever hold my hand and I was scared that you only said you loved me because you are my father’s student and you wanted to be a good student because that is the only thing that is important to you?

Oh Dear, My Gurion,

That last question was the question I was asking myself from the time we broke up until one week ago today, when you came over and learned the doubling cube, and I thought: Some people, even very smart people, play sheishbesh without the cube, and they don’t even know they’re playing without the cube because they don’t even know there is a cube…they don’t know what the cube means, these people, and if you were to offer them the cube in the middle of a game you were playing with them, they wouldn’t even know that an offer had been made — they would think you were just pushing dice at them, and maybe not even that because maybe they’d only think you were doing something nervous with your hand to the dice. And I thought: Gurion is one of these people.

Читать дальше