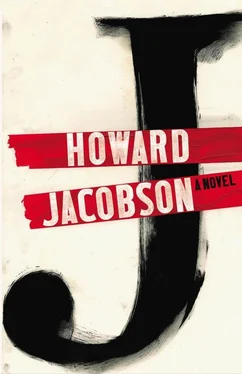

Densdell Kroplik had told him, the last time they met, that he was lucky to have been born in Port Reuben. Lucky ? The thought that he owed anything to chance disheartened him. If he was only here by chance then he was indeed chaff in the wind and might as easily have been blown somewhere else. So where? Absolutely anywhere , was the answer, but how do you live a life that isn’t random when the circumstances of your living it are? There had to be something between him and Port Reuben that was more than fortuitous; each had to have needed the other. All right, he accepted Kroplik’s view of him as a child of aphids who were themselves children of aphids. No one can go all the way back to the beginning. Invaders, migrants, vagrants, came and went. He’d settle for ten generations. If he had to, he’d make do with even fewer. Soil was all he was after. Not real soil, God forbid, but the idea of soil. If not native soil then soil that at least was congenial to his growing. Bodies rejected implanted organs; some took but others the body found too alien. Why did he feel that the village of Port Reuben, in which his papers certified he’d been born, had always been rejecting him like an organ it didn’t need or want?

This rummaging through his parents’ papers was not going to help him find an answer. It never had before. Yet each time he did it he came upon something he hadn’t paid attention to previously. A  oke so acidic that it had burned through the paper on which his father had written it. The names of

oke so acidic that it had burned through the paper on which his father had written it. The names of  azz records he intended to buy. Titles of books still to be read. A manila folder containing a few watery sketches, none of them remarkable, done by his mother presumably, of him as a baby, of his father as a younger but no less rancid-looking man, of a beautiful dreaming woman he didn’t recognise but whom now, after Kroplik’s description, he took to be his grandmother, of the cliffs, of a sunset, and of hands — just hands — drawn so tenderly they had to belong to her butcher-lover. So they’d lived here at least, his mother and father — because bitterness and infidelity constitute lives.

azz records he intended to buy. Titles of books still to be read. A manila folder containing a few watery sketches, none of them remarkable, done by his mother presumably, of him as a baby, of his father as a younger but no less rancid-looking man, of a beautiful dreaming woman he didn’t recognise but whom now, after Kroplik’s description, he took to be his grandmother, of the cliffs, of a sunset, and of hands — just hands — drawn so tenderly they had to belong to her butcher-lover. So they’d lived here at least, his mother and father — because bitterness and infidelity constitute lives.

He missed their lives for them, missed what he didn’t remember, yearned for what he hadn’t known. Can you be nostalgic for nostalgia, he wondered. His answer was yes, yes you could.

It was while he was again, ritualistically, going through drawers in his father’s workshop that he came again upon a foolscap black notebook with scribbled entries in his mother’s hand. It hadn’t interested him the first time he’d found it, because it seemed to contain no more than lists of non-essentials his father must have asked for, sacks for rubbish, a new coffee mug, a fan heater, antiseptic cream. But he realised he should have wondered why it was here, in his father’s space, among his father’s things. After the first half-dozen pages the book became something else. Sketches again, but not at all watery this time: strong charcoal portraits, in the manner of woodcuts — had she been thinking of actually doing woodcuts with her husband’s help? — of people he didn’t recognise, squatting careworn women in turbans, angular men in long beards, carcasses of slaughtered animals, executioners in bloody aprons standing over them, a child looking out of the barred window of a train, figures huddled in fear, and one of herself, he was sure it was her, with her mouth open and a hand, not hers, over it, pressing hard into her face. And then, at the back of the book, half a dozen small crayoned studies in a style so different he marvelled the same person could have done them — what they depicted he couldn’t say for sure, cityscapes a couple of them seemed to be, whores, or were they birds, cranes or storks, standing under phosphorescent yellow lamp posts, their scarves or feathers blowing about their necks, their bodies rendered in patches of the most vivid colour, purple shoulders and breasts, vermilion bellies, attenuated lime-green legs, the stones they stood on as black as night. Two were more abstract still, mere blobs of violent colour, like pools of blood, and one a nude, somehow African in conception, primitive certainly, painted freely, her eyes orange, her skin a throbbing pink, her hands stretched out towards. . towards whom?

Could his mother really have done these? They were signed, simply but deliberately, in upright letters, as though she wanted there to be no mistake about it, Sibella.

He had always discounted his mother. Other than when he heard her calling to him on the cliffs, he rarely thought about her. It was his father he had grieved over, not out of love but out of sorrow. His father had made small beautiful things. Miniature ring bowls whose rims fell away like lace around wrists, mahogany trinket boxes with secret compartments so finely concealed that people who hid things in them sometimes never found them again, slender swaying single-rose vases carved out of ‘whispering walnut’ — his father’s phrase, whispering this, whispering that, their whole lives lived in a whisper. How could such delicacy of work proceed from so frightened, unhappy and lumpen a temper? His mother too had been unhappy, but she was no artist and Kevern Cohen was sentimental about art. Now he had to revise his thinking.

His father had kept this folio of hers. Why? Did he secretly admire her gift? Did he ever tell her, Kevern wondered.

It even crossed his mind, for the very first time, that his father and mother might have loved one another. The idea, at least, of his father being proud of her, made him tremble with the realisation that he’d known as little about his family as he knew about the earth he trod on.

How good an artist was she? He couldn’t tell. Her hand was strong and sure, the colours piercing, but were the images hers? He felt he had seen some of them before, or at least that they gave off an atmosphere he had breathed before. Even had they been copies, they were good, for copies too are distinguishable by the feeling they show. But where had she seen such work to copy? He couldn’t recall her ever having left the village. Nor did he remember her poring over art books. And if they were hers entirely, out of what depths of visionary dread had she drawn them?

He knew someone he could ask. Ailinn. But if he suddenly rang her to say he had unearthed remarkable art made by his mother she would smell a rat. If you want to talk to me, just talk to me, Kevern , she would say. You don’t need a pretext . Besides, what if she didn’t value the work? She wouldn’t be able to say so. And thereafter there’d be a dishonesty between them. It wasn’t fair to ask her.

Then he remembered someone else. Everett. Professor Edward Everett Phineas Zermansky.

iv

‘And these were done by whom again?’ the eminent professor asked.

He was nervous. Only nerves could explain such a question, given how clear Kevern had been about finding the notebook in a drawer in his father’s workshop, how he recognized other entries in her hand, and how sure he was of her signature. Did Zermansky feel he’d been compromised by Kevern’s excitement because it showed that he wasn’t only illegitimately hoarding heirlooms but hankering inordinately for something in the past? Surely not. Everyone knew that everyone else kept more than they should. Curiosity had not been altogether stifled anywhere.

‘My mother. I told you.’

‘And you never knew?’

‘Never.’

‘Never saw her do these?’

‘Never.’

‘So they might not be hers?’

‘Believe me, that’s her signature.’

Zermansky shrugged. In the world of art a signature was nothing.

Читать дальше

oke so acidic that it had burned through the paper on which his father had written it. The names of

oke so acidic that it had burned through the paper on which his father had written it. The names of