Ha! — she had forgotten.

It was a good job that history books were hard to come by, that diaries were hidden or destroyed and that libraries put gentle obstacles in the way of research, otherwise she might have decided to ransack the past and live her life backwards. If only to discover who it was her heart periodically fluttered for.

A sodden old snail appeared from under her bed, dragging a smear of egg white behind it. It was all she could do not to crush it with her bare, ugly foot.

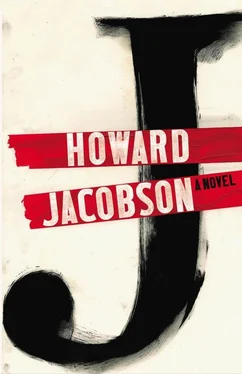

Before chancing his nose outside his cottage in the morning, Kevern ‘Coco’ Cohen turned up the volume on the loop-television, poured tea — taking care to place the cup carelessly on the hall table — and checked twice to be certain that his utility phone was on and flashing. A facility for making and receiving local telephone calls only — all other forms of electronic communication having been shut down after WHAT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED, to the rapid spread of whose violence social media were thought to have contributed — the utility phone flashed a malarial yellow until someone rang, and then it glowed vermilion. But it rarely rang. This, too, he left on the hall table. Then he rumpled the silk Chinese hallway runner — a precious heirloom — with his shoe.

The action was not commemorative in intent, but it often reminded him of a cruelly moonlit night many years before, when after a day strained by something — money worries or illness or news which the young Kevern gathered must have been very bad — his sardonic, creaking father had kicked the runner aside, raised the hem of his brocade dressing gown, and danced an enraged soft-shoe shuffle, his arms and legs going up and down in unison like those of a toy skeleton on a stick. He hadn’t known his son was on the stairs, watching.

Kevern pressed himself into the darkness of the stairwell. Became a shadow. He was too frightened to say anything. His father was not a dancing man. He stayed very still, but the cottage thrummed to its occupants’ every anxiety — he could sense his parents’ troubled sleep through the floorboards under his bed, even though he slept in a room below theirs — and now the disturbance his fear generated gave his presence away.

‘Sammy Davis  unior,’ his father explained awkwardly when he saw him. His voice was hoarse and dry, a rattle from ruined lungs. Because he spoke with an accent even Kevern found strange, as though he’d never really listened to how people spoke in Port Reuben, he released his words reluctantly. He put two fingers across his mouth, like a tramp sucking on a cigarette butt he’d found in a rubbish bin. This he always did to stifle the letter

unior,’ his father explained awkwardly when he saw him. His voice was hoarse and dry, a rattle from ruined lungs. Because he spoke with an accent even Kevern found strange, as though he’d never really listened to how people spoke in Port Reuben, he released his words reluctantly. He put two fingers across his mouth, like a tramp sucking on a cigarette butt he’d found in a rubbish bin. This he always did to stifle the letter  before it left his lips.

before it left his lips.

The boy was none the wiser. ‘Sammy Davis  unior?’ He too, religiously in his father’s presence — and often even when his father wasn’t there — sealed his lips against the letter

unior?’ He too, religiously in his father’s presence — and often even when his father wasn’t there — sealed his lips against the letter  when it began a word. He didn’t know why. It had begun as a game between them when he was small. His father had played it with his own father, he’d told him. Begin a word with a

when it began a word. He didn’t know why. It had begun as a game between them when he was small. His father had played it with his own father, he’d told him. Begin a word with a  without remembering to put two fingers across your mouth and it cost you a penny. It had not been much fun then and it was not much fun now. He knew it was expected of him, that was all. But why was his father being Sammy Davis

without remembering to put two fingers across your mouth and it cost you a penny. It had not been much fun then and it was not much fun now. He knew it was expected of him, that was all. But why was his father being Sammy Davis  unior, whoever Sammy Davis

unior, whoever Sammy Davis  unior was?

unior was?

‘Song and dance man,’ his father said. ‘Mr Bo  angles. No, you haven’t heard of him.’

angles. No, you haven’t heard of him.’

Him? Which him? Sammy Davis  unior or Mr Bo

unior or Mr Bo  angles?

angles?

Either way, it sounded more like a warning than a statement. If anybody asks, you haven’t heard of him. You understand? Kevern’s childhood had been full of such warnings. Each delivered in a half-foreign tongue. You don’t know, you haven’t seen, you haven’t heard. When his schoolteachers asked questions his was the last hand to go up: he said he didn’t know, hadn’t seen, hadn’t heard. In ignorance was safety. But it worried him that he might have sounded like his father, lisping and slithering in another language. So he spoke in a whisper that drew even more attention to his oddness.

In this instance his father needn’t have worried. Kevern hadn’t only not heard of Sammy Davis  unior, he hadn’t heard of Sammy Davis Senior either.

unior, he hadn’t heard of Sammy Davis Senior either.

Ailinn would not have said no to such a father, no matter how strange his behaviour. It helped, she thought, to know where your madness came from.

Once Kevern had closed and double-locked the front door, he knelt and peered through the letter box, as he imagined a burglar or other intruder might. He could hear the television and smell the tea. He could see the phone quietly pulsing yellow, as though receiving dialysis, on the hall table. The silk runner, he noted with satisfaction, might have been trodden on by a household of small children. No sane man could possibly leave his own house without rearranging the runner on the way out.

He had a secondary motive for shuffling the rug. It demonstrated that it was of no value to him. The law — though it was nowhere written down; a willing submission to restraint might be a better way of putting it, a supposition of coercion — permitted only one item over a hundred years old per household, and Kevern had several. Mistreatment of them, he hoped, would quiet suspicion.

At the extreme limit of letter-box vision the toes of worn leather carpet slippers were just visible. Clearly he was at home, the fusspot, probably nodding in front of the television or reading the  unk mail which had in all likelihood been delivered only minutes ago, in the excitement of collecting which he had left his tea and utility phone by the door. But at home, faffing, however else you describe what he was doing.

unk mail which had in all likelihood been delivered only minutes ago, in the excitement of collecting which he had left his tea and utility phone by the door. But at home, faffing, however else you describe what he was doing.

He returned to the cottage three times, at fifteen-second intervals, looking through his letter box to ascertain that nothing had changed. On each occasion he pushed his hand inside to be sure the flap had not stuck in the course of his inspections — a routine that had to be repeated in case the act of making sure had itself caused the flap to  am — then he took the cliff path and strode distractedly in the direction of the sea. The sea that no one but a few local fishermen sailed on, because there was nowhere you could get to on it — a sea that lapped no other shore.

am — then he took the cliff path and strode distractedly in the direction of the sea. The sea that no one but a few local fishermen sailed on, because there was nowhere you could get to on it — a sea that lapped no other shore.

Nothing had changed there either. The cliff still fell away sharply, sliced like cake, turning a deep, smoky purple at its base; the water still massed tirelessly, frothing and fuming, every day the same. Faffing, like Kevern. More angrily, but to no more purpose.

That was the great thing about the sea: you didn’t have to worry about it. It wasn’t going anywhere and it wasn’t yours. It hadn’t been owned and hidden by your family for generations. It didn’t run in your blood.

Читать дальше

unior,’ his father explained awkwardly when he saw him. His voice was hoarse and dry, a rattle from ruined lungs. Because he spoke with an accent even Kevern found strange, as though he’d never really listened to how people spoke in Port Reuben, he released his words reluctantly. He put two fingers across his mouth, like a tramp sucking on a cigarette butt he’d found in a rubbish bin. This he always did to stifle the letter

unior,’ his father explained awkwardly when he saw him. His voice was hoarse and dry, a rattle from ruined lungs. Because he spoke with an accent even Kevern found strange, as though he’d never really listened to how people spoke in Port Reuben, he released his words reluctantly. He put two fingers across his mouth, like a tramp sucking on a cigarette butt he’d found in a rubbish bin. This he always did to stifle the letter