‘I did, sometimes. Some nights I thought it was a great wrong. But this is different. Whatever they say, it’s different.’

‘Do you want to come to my bed?’

He looks at her. In the dark he can just make out the grey pinpricks of her eyes. A faint custard glow, like that of street lights, comes yellowing off her hair. This is the first time she has offered them her bed. Though there has been no need of the bed, he has noticed the omission. Henry doesn’t have thin skin for nothing. He knows what isn’t offered, whether there is need of it or not. What’s downright refused, Henry logs under Miscellaneous Insults; what merely isn’t offered, he files under Sundry Hurts. That she hasn’t offered he has taken to be delicacy on her part. The woman preserves the memory of her bed, the history of its associations and fidelities. Whereas the man behaves like a pig. Jump in. Sure, I did once share this with my wife, but a new day’s a new day! And if you really want me to I will launder the sheets. Henry had no wife. Not of his own. So it was his father’s memory he besmirched — correction, his mother’s. But now Moira has compromised her delicacy to save his. Henry takes the full measure of this. It is like a proposal of marriage. In the dark he gathers her into his arms and kisses her.

But there is no reason to move out. He isn’t feeling fastidious. He presses the part of himself where qualms gather and finds no softness. Tries to imagine his mother and Mr Yafi lying here, but no picture will form. Good. Tries to imagine their imagining him, but no picture will form of that either. Good again. Even when he puts on Schubert’s Fifth Symphony — ‘How lovely you are, how lovely-ey-ey you are’ — and tries imagining her singing it to her lover, the Moor, he is unable to locate anguish of the Hamlet kind. A cistern of tears when he thinks of his mother normally, suddenly Henry is dry. What, not even some creaking at the temples? He listens. Nothing. Behind the cheekbones, though, he can make out distant pain. Like needles going in, and a sound like splintering. And that too is good. He wants to be upset.

For what has happened is upsetting — both the fact of it and its coming into his possession — but it is upsetting in the way everything that bears on change and forgetfulness is upsetting. . and that’s the end of it.

So, no, he is all right about where he is. It was all a long time ago.

The distress he feels is centred somewhere else. He searches for it, even as Moira lies folded like one of his father’s napkins in his arms, searches for it in the rhythm of her breathing. The association isn’t accidental. His father. He can’t bear it for his father. This isn’t a straight exchange of sorrows: giving to his father the sympathy which had once belonged, unthinkingly, to his mother. It’s worse, was worse, for his father. His father had no words. You can’t breathe out your grief in fire. You can’t cut dollies out of paper to express your longing. Crist, if my love were in my arms . . What means did his father possess to body forth yearning of that sort? Why, even when he tried to talk to Henry, Henry looked away in embarrassment. That’s what you do with dads; you piss them off. Mums you open your hearts to, dads you turn your back on.

Did the Stern Girls know? Did the secret they were keeping for Ekaterina die, as far as they were concerned, with Marghanita?

‘The poor child!’

Henry never asked Marghanita who that poor child was. She was too far gone to tell him, even supposing she knew herself. That was how he explained it, anyway. Never was much of an asker of questions, Henry. Too afraid of the answers. And didn’t like to be beholden. Better to lower your eyes and nod your head and pretend to know. What you don’t ask doesn’t hurt you. And who you don’t ask doesn’t hurt you either.

Also, he had thought it was a composite. The poor child, meaning Marghanita, seen at the eleventh hour as a third party, someone not herself, to be sorrowed over because of the circumstances in which she had come, illegitimately, into the world; and meaning Henry as well. Poor Henry, to be sorrowed over by Marghanita because of the circumstances in which he had failed to conquer the world, when they laid it on a plate for him. Here, Henry, have! Have! Only he wasn’t sure how to take it. Poor her, poor him. More recently, since the sighting of the bench in Eastbourne, he has wondered if the poor child could have been his mother too. Poor abandoned Ekaterina, scratching at the earth to find a place of peace.

Now he has another thought.

His father. The father who never grew up.

He remembers that it was Marghanita who told him that his father had been encouraged to think for years that Passover was a party just for him. The poor child. Did Marghanita also know that later he grew frantic for his wife, not understanding why her attention had wandered from him, not grasping that she had bestowed her heart upon another man, only dimly aware — for dim awareness was the best his father ever managed ( taugetz , Henry) — that though she remained with him most of the time in body, an audience for his fireballs and his origami, in every other respect she was somewhere else, wife to a husband who was not him. An Arab who loved her.

You could do it, presumably, with pages torn from this book, but Henry’s father recommended three sheets of newspaper of the sort he never read — The Times, Telegraph, Observer . ‘Three full sheets’, was the instruction. No half-measures for Izzi. If you’re going to go for it, you go for it. A) three full sheets of newspaper, B) a rubber band, C) a pair of scissors.

These for the making of a paper beanstalk, twice as tall as yourself . Depends who the self is of course, but Izzi Nagel had in mind an averagely small child, say Henry the size he was when he fucked up with the threepenny bit.

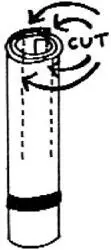

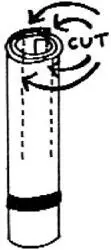

Then what you do is you fold the newspaper in half lengthwise and tear along the fold to make six strips. Take one of these strips and roll it into a tube about two inches in diameter, like so:

When you have got six inches from the end, you take a second strip, insert it, and continue rolling.

Now go on doing the same until all the strips are used up. .

In his mind’s eye, perhaps because he was there at the proof stage when his father was preparing his little book of tricks and puzzles for the printer, Henry can still see the triumphant concluding page to this particular example of paper magic, the mounting excitement, the mind-spinning arrows etched with such urgency, as though disaster would surely befall you if your cutting went awry, the exhortation to believe, and the final great flowering beanstalk of newsprint, growing beyond a boy’s capacity to imagine.

Put the rubber band firmly round one end:

Cut or tear the roll as straight as you can at the four places shown by the dotted lines:

Then fold back the flaps:

Читать дальше