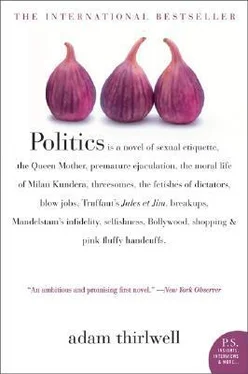

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

3

Nana did not immediately answer Papa’s question. She did not immediately tell him when she would go back to Moshe. Instead, sitting with Papa on Papa’s bed, she opened the post. The post, this morning, was one card. It was a card of condolence from their family friend and dentist, Mr Gottlieb.

Dear Nina,

What a great loss your father is.

With best wishes from Luke Gottlieb.

She giggled. She read it out. They both giggled.

‘What a bastard!’ said Papa. ‘That’s what he sends when I’m dead? One sentence? Give it me.’ Papa read it. He read it again. ‘What a bastard!’ said Papa. Nana put the card on the window sill. It did not balance. She flexed the card out. It balanced. Papa said, ‘And what were you doing, telling him I was dead? Why was he sending the card at all, that’s what I want to know.’ ‘I can’t remember,’ said Nana. ‘I dint say a thing. I said, no I dint say a thing.’

Of course, this was not true. She had wept and told Mr Gottlieb that she was terrified of Papa dying. Mr Gottlieb must have misheard. But Nana could not tell Papa that she was scared he might die. No. Nana was too careful for that. She was too kind.

Papa said, ‘So. How’s Moshe? You haven’t said. When are you going back?’ And Nana said, ‘Mnot going back.’ This surprised Papa. He said, ‘What?’ Nana said, well she sighed and said, ‘I broke up with Moshe.’

This surprised Papa much more. It upset him. He tried to say something calm. He said, ‘You?’

Nana said, ‘We broke up.’ Papa said, ‘But why? He was a sweet boy. Why did you break up with him?’ ‘I wanted to,’ said Nana. ‘But why?’ said Papa.

‘I wanted to be with you,’ said Nana.

She was making a gesture of pure love, she thought.

But Papa did not want her to make gestures of pure love. And nor do I. He was feeling horrified and amazed. Papa was not a selfish person. He was not an egotistical patient. He was thinking that he could not let Nana do this. ‘With me?’ said Papa. ‘But you need to be with Moshe.’ He could not let her nurse him, thought Papa. She had a boy, she had a life. He could not let Nana waste time on her Papa.

‘No I wanna be with you,’ said Nana. ‘You go back to Moshe,’ said Papa. ‘You go back and say that you are sorry. You tell him you’ve changed your mind. You can’t break up with Moshe because of me. It’s crazy,’ said Papa. ‘I mean, how long were you thinking? How long were you thinking of staying with me?’

Suddenly, Papa felt tired. He felt very tired and sad.

I am living too long, Papa thought.

You see, Papa’s stroke or possible tumour had caused a particular conundrum. The prognosis was only approximate. Even if it were a tumour, they told him, Papa could still live for another twenty years. He could also die the next day. This lack of predictive accuracy distressed Papa. If Nana had to nurse him for only a week, then he might not have minded. But nursing could mean anything. It could mean years.

He was confused. He thought he was living too long. His life was wasting Nana’s life. He was wasting everything. Even the money was wasted. His nursing was expensive. And Papa did not want to use up money for the next twenty years that could have gone to his darling girl.

Papa is the benevolent angel of this story. You need to remember this.

He said, ‘Look this is crazy. I don’t need a minder.

There’s the nurse comes in every day. I don’t even need the nurse. I’m fine. You don’t need to stay with me.’

This was both generous and mean. That might sound like a contradiction, but it was true. It was generous of Papa. It was mean to Nana.

4

Vaclav Havel’s letter to Dubccek had a hidden agenda, I think. Vaclav was responding to another, rival theory of nobility. According to this theory, making possibly useless noble gestures is not noble at all. No, it is just a form of exhibitionism. An act that might seem noble is therefore just egotistic.

Of course, Vaclav would not imagine that the motives of noble acts could ever be doubted. Well, he might concede the possibility. But he would not see the point. He believes in transcendent morality, does Vaclav. In an interview, Disturbing the Peace, he states: ‘I believe that nothing disappears for ever, and less so our deeds. ’ He will have no truck with people who are sceptical. He will not kowtow to more complicated Czech dissidents, like Milan Kundera.

In 1968, you see, a year before Vaclav’s letter to Dubcek, Milan and Vaclav had fallen out. I am going to give you a quick sketch of this argument.

In December 1968, Milan wrote an article called ‘Cesky udel’. This means ‘The Czech Destiny’. In it, Milan was not defeatist. He was not going to get downcast by the Russian invasion. Milan pointed out that, so far, Dubcek’s reform policies had not been abandoned. There was no police state. There was freedom of speech. There was the possibility — for the first time, thought Milan, in ‘world history’ — of creating a new democratic socialism. So the people who were publicly concerned about the Soviet future, concluded Milan, were ‘simply weak people, who can live only in illusions of certainty’. They were not moral at all.

But Vaclav did not like this essay. In February 1969, he wrote an essay called ‘Cesky udel?’ This means ‘The Czech destiny?’ He did not agree that publicly asking for guarantees was so bad. He thought it was important to allay people’s quite reasonable concerns. Milan’s vision of Czechoslovakia at the centre of world history was, thought Vaclav, sentimental.

In reply, Milan wrote another article. This one was called ‘Radikalismus a Exhibicionismus’. This means ‘Radicalism and Exhibitionism’. In it, Milan tried to explain what he had meant. He thought that all these worries about the Russians and police states just displayed ‘moral exhibitionism’. That was what he disliked. And Vaclav, thought Milan, was also suffering from this ‘illness of people anxious to prove their integrity’.

Although Vaclav seemed noble, therefore, he was just an exhibitionist.

I am not interested in who turned out to be right here. In retrospect, some people might think that Milan was wrong. It does not seem to be the perfect moment, when the Soviet tanks are trundling round the streets of Prague, to be quibbling over ethics. But actually, I do not think he was wrong. Milan was not morally naive. He was making a very true and important point. It is possible, after all, for an act to seem altruistic, but really just be self-serving.

That is a complication.

In the vocabulary of this novel, for instance, staying with Papa would seem noble but really it would be self-serving. The apparent nobility of Nana’s sacrifice would simply be motivated by her desire not to watch Moshe make Anjali come. I am not saying this is entirely true. I am just saying that’s how it would be.

But Vaclav would not admit this. And that is why I do not love Vaclav. But I do love Milan Kundera. I love him very much.

5

‘Don’t you want me to stay with you?’ asked Nana. She was distressed. And Papa said, ‘Sweetness, of course I want you to stay with me. Well no I don’t want you to stay. But it’s not because I wouldn’t like it. I want you to go back to Moshe. It’s crazy. This is crazy.’

This is the ending. It is where everything gets turned upside down.

Nana said, ‘But I can’t go back.’ ‘You can’t go back,’ said Papa. ‘You can’t go back to Moshe.’ ‘Because he’s going out with someone else,’ said Nana. ‘With someone else? Already?’ said Papa. ‘He’s, he’s going out with Anjali,’ said Nana.

‘Oh darling,’ said Papa. ‘Oh I’m sorry.’ ‘Sokay,’ said Nana. ‘Sokay. So I can be with you.’ ‘So he broke up with you,’ said Papa. ‘No,’ said Nana. ‘No, I broke up with him.’ ‘Well it certainly seems like Moshe did better out of this,’ said Papa. ‘He certainly seems to be doing quite well to me.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.