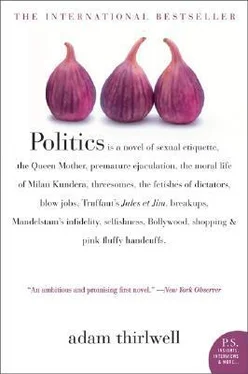

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And that is the last you will see of Moshe. The last you will see of him is this moment, after Nana had broken up with him, when he orders a salt-beef bagel in the Kosher Knosherie.

I can understand why Moshe felt emotional there, in the Kosher Knosherie. It was the Jewish 1950s. Printed on the centre of each plate, in pork pink, there was a massive B and then ‘uy loom’s est eef’ vertically arranged to its right. It was an older world. It was bright pink oilcloth, and gilt curved swirls for chairbacks. It was a much safer and happier world.

And I can recognise this feeling. When I am there, I feel emotional too.

13

But I am not going to get emotional. I am not going to get sad. No. I am going to describe happiness instead. Although, at this point in the story, I do not have many options.

I will try to describe Nana’s happiness.

Edgware was making Nana happy. She liked living in Edgware. Because Papa lived there and enjoyed it, Nana thought that Edgware was cool.

Perhaps you have never been to Edgware. Perhaps you cannot understand what an odd variety of happiness this was. Edgware is at the end of the Northern line. It is, therefore, not exactly urban. It is definitely suburban. The tube station was designed in 1923 by S. A. Heap, in a restrained neo-Georgian style. Each year, the station forecourt puts up a ten-foot high menorah, in celebration of Chanukkah. If you turn left out the station, you walk past McDonald’s and the entrance to the Broadwalk Shopping Centre.

On Saturday nights, when shabbat is over, a collection of Jewish boys and girls congregate with black and Asian boys and girls outside McDonald’s. They sell each other drugs. Sometimes, to pass the time, they get on the tube to

Golders Green and stand outside Golders Green station. Then they come back to Edgware station.

Edgware is a multicultural haven.

If you carry on past McDonald’s, you also pass a newsagent, which is sponsored by the Jewish Chronicle. There is a board outside the newsagent, also sponsored by the Jewish Chronicle . The board is part of the deal. It is where they advertise their headline stories. When Nana returned home, to look after Papa, the Jewish Chronicle ’s main story was this.

‘Win a Pesach holiday for Four in Majorca!’

I am afraid that this, combined with the ten-foot high menorah, made Nana feel sad. It made her nostalgic. Well, perhaps not nostalgic exactly. She was not Jewish at all. Israel was not her personal homeland. She was just thinking sad upset and tragic thoughts about one adorable Jew in particular.

You have to remember. She loved Papa. But she loved Moshe too.

Past this newsagent, on your right, is where the Belle Vue cinema used to be. If you carry on walking, however, you soon come to the architectural extravaganza of the Railway Hotel. The Railway Hotel was built in 1931 by A. E. Sewell in an unrestrained mock-Tudor style, complete with its own fake gallows. And that is the end of Edgware High Street.

Edgware is suburban. It is dismal, quiet, lovable and kitsch.

But no, actually there was another person in this story who was happy. In a way, at this point, she was even more happy than Nana.

Anjali was sitting in Moshe’s flat, sleepily dozing. She was sitting in Moshe’s flat and thinking about Nana. She was also thinking about Moshe.

Anjali was thinking about love.

I want you to remember Anjali. You must not read this carelessly.

Anjali was remembering her Bollywood films. The loveliest Bollywood film she had seen was Devdas. This film was very moving. In its closing scenes, as Shah Rukh Khan dies outside the gates of Aishwarya Rai’s house, it shows how wonderful and powerful love is. It shows, thought Anjali, that love is stronger than anything.

And I think that Anjali was right. I like her, I really do. But I especially like her, I think, because although she was drifting off, thinking about the wonder and power of love, she was still practical.

Because Anjali was practical, she was nonplussed. She could not quite understand what she was feeling. It was not love. She knew that. It was just that she was happy. She was suddenly and surprisingly happy.

III

11. The finale

1

As papa saton his duvet, with its innovative design of small white lions and falcons and fruit trees on a magenta background, he chatted to Nana about her sweet boyfriend Moshe.

Papa liked Moshe. He liked Moshe very much.

Anjali is not the ending. Surely you must have known that. I was not going to end with Anjali on her own, being happy. No. I started with a bedroom scene and I’ll end with a bedroom scene.

‘Anyway. How is Moshe?’ said Papa. ‘When are you going back?’

Before we go any further, I am going to describe Papa’s get-up. His get-up was unusual. It was one red Tote sock, one navy Tote sock, a pair of black suit trousers — whose zip was done up but whose button was not — and a white T-shirt printed with a picture of a curlybearded satyr that Papa had bought in Rhodes in 1987.

So, now I can start again. I just wanted you to get his day wear right.

‘Anyway. How is Moshe?’ said Papa. ‘When are you going back?’

You see, Papa did not know that Nana had left Moshe, for ever. Nana had not told him. This was because she did not want to embroil him in her love life. She wanted Papa to feel entirely loved by Nana. And this meant that she could not tell him that Moshe and Nana were no longer together. It would complicate her gesture of pure love. It would make it seem less sincere.

Because Nana was making a gesture of pure love. It was true.

2

I think you should not judge Nana’s secrecy here, about her split with Moshe, as entirely crazy. It is very difficult, being moral. It is, I reckon, almost impossible. You have to rely on all kinds of generalisations and theories.

One generalisation is this. People often think that a noble gesture is inherently better than a pragmatic gesture. Even if it is ineffectual and potentially harmful to oneself, a noble act is still noble, it is still moral.

In the vocabulary of this novel, then, staying with Papa is better than staying with Moshe. It may be self-destructive, and potentially harmful to Nana’s eventual happiness, but it is more virtuous.

Nana would find a supporter for her theory in the Czech dissident and ex-president, Vaclav Havel. On 9 August 1969, when he was a dissident, Vaclav wrote a letter to the former Czech president, Alexander Dubcek. This was a year after the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia. The Russians had invaded because of Dubcek’s softer, nicer version of communism. They had made Dubcek resign as president, but had allowed him to stay in parliament. However, they did not leave him alone. They wanted him to publicly repudiate his nicer version of communism.

Vaclav did not want Dubcek to do this. Vaclav wanted him to affirm his belief in his nicer version of communism, even if this was dangerous for Dubccek and would have no effect whatsoever. That was why he wrote his letter to Dubccek, imploring him to be noble.

Because, wrote Vaclav, ‘even a purely moral act that has no hope of any immediate and visible political effect can gradually and indirectly, over time, gain in political significance’.

Vaclav means that we should not laugh at useless and self-harmful moral gestures. They are not necessarily just for show. They are not necessarily gestures. Some good might eventually come of them.

Unfortunately, Vaclav’s theory never got a chance to be tested. In September 1969, the Russians removed Dubcek from parliament as well, a month after Vaclav’s letter. Vaclav never got a reply.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.