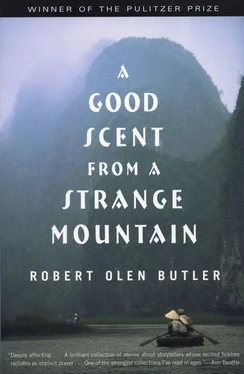

She lifted the dragon high with both hands and raised it over her, and she slowly brought it down: her hair, her brow disappeared into the dragon, her eyes and her nose and her mouth, my daughter’s face disappeared into great bright eyes, flared nostrils, cheeks of blood red and a brow of green. And Tri’s daughter clapped her hands and laughed and the dragon head angled down and opened its mouth to her as if to cry out.

I looked at Binh and he was waiting for me to speak and I looked at the others and then at Th  o, Her face was slightly turned to me but her eyes were lowered. I thought, It’s been nearly twenty years since I first lay down with you and touched those places on your body that were smooth and soft and that are coarser now, and I love them still, I love them more for their very coarseness. I do not wish to open the past either, my wife. But this is my village and I was seen across a field by millions and the eyes of that other country turn this way.

o, Her face was slightly turned to me but her eyes were lowered. I thought, It’s been nearly twenty years since I first lay down with you and touched those places on your body that were smooth and soft and that are coarser now, and I love them still, I love them more for their very coarseness. I do not wish to open the past either, my wife. But this is my village and I was seen across a field by millions and the eyes of that other country turn this way.

I let a little of the past back into me then, and I did not know what to say. A house with a wraparound porch and maple trees and a grass yard cut close and edged each week in a perfect line along a sidewalk: things unknown in this place. Things that I could see without pain only when they sat unpeopled in my head. Things of a family that were worth keeping only from a summer day when the maple leaves did not stir and when no one from inside this house was visible, no sounds could be heard from inside. How to say that for these Vietnamese who sensed — always — even the dead spirits of a family? Who in this circle could imagine that only this was good in that past life of mine: a maple tree and the smell of fresh paint on the porch, just dried into a Victorian green and smelling like something new, and the creak of a chain on a swing there, my feet touching and pushing, lifting me as if I was flying away.

And these thoughts frightened me. I was thinking about these Vietnamese now from a distance, how they could not know me, and I wanted to blame this distance on that other self that was creeping back in, but it was hard now entirely to do that. After all, this was my past and the haunches it crept on could find strength only from me. And Tri’s daughter shrieked and laughed across the way and there was a faint, muffled roaring that I recognized as my daughter’s voice and I knew not to look. I could not look at that.

And I rose up from where I crouched and I said, “I’m sorry,” and I stepped out of the circle and I did not look at my wife and I did not look at my daughter and I hesitated only for a moment and I knew that no one here would ask me again to speak of this and that was their way and I looked along our village street, down a little slope to a closing of the trees, the road I had followed when Binh first saw me weary and ready to sleep. And I took one step now in that direction, toward the trees, and another step, and I walked away.

I walked for a long time and went up, into a piney wood, and this was an American smell, as American as it was Vietnamese. There were two tall pine trees in the yard behind the house with the wraparound porch and it smelled just like this and there was a chill that made me tremble briefly, tremble in the chest, in the heart, right then, passing through the shadow of a great isolated pine in a little clearing and open to the wind, and the nights in the highlands could be American, too, it could be cold at times here in Vietnam, even in this country of rice paddies and water buffalo.

And I stopped and I sat on a knoll and I looked at my hands darkened by the sun, not as dark as my wife’s skin or Binh’s or any of the others in the circle I’d broken but as dark as the skin of a Vietnamese child, that dark. This could be the skin of a Vietnamese child. Except for the blond hairs on my knuckles, and I looked at my arms and there was a forest of blond hair on this dark arm, and I was on the porch swing, in the very center, and my arms were taut, my legs were just long enough now to touch and push and lift and my arms were rigid grasping the lip of the seat, and for a moment there was only the cry of the chain above me: I pushed and the chain cried out, over and over, and it seemed painful to this thing for it to carry me, and I rose but always came down again and I never did move from the porch, and I stopped and I sat and still there was silence from the house but I knew I would go in. Against all that I desperately desired, I would go in.

Binh was asking me to go in. They all asked me that now. Just to have me speak. I was to walk into the great bland jaws of that house and what I feared was this: perhaps a family scattered even to the other side of the earth did not truly cease. Once I went in again, perhaps I could never return to Vietnam. I sat now and waited and trembled and nothing came to me to do.

But I could not sit in the woods and I rose and I went back down to the path and I walked again into the village and I went past the vegetable garden and there were three women there in conical straw hats and I knew their names and I knew their children and I passed the house of Tri and the house of Quang and the houses of others whose names I knew, whose children I knew, and I stopped in front of Tiên’s house and there was the smell of wood fire from her kitchen and the smell of incense and the dragon’s head was sitting in her doorway now and smelling of paint. There was the smell of fresh paint in her doorway and they all came, gradually. Tiên first and then Binh and then the others, all of them came, and my wife came and Hoa was with her and about to go away and I shook my head no and then nodded her to the circle that was forming.

Hoa crouched beside me and Th  o next to her, anxious still, I knew, and my daughter turned her face up to me and then away and I leaned near and her hair smelled of the rain, smelled of the water that we gathered in a great stone pot, as is our way here, and we believe that the spirits of our ancestors come close to us and need our prayers, the prayers in our houses with the smoke of incense rising, and I understood how odd and wonderful the air of this village was now because I came here and married and made this child. The air here was filled with the spirits of Th

o next to her, anxious still, I knew, and my daughter turned her face up to me and then away and I leaned near and her hair smelled of the rain, smelled of the water that we gathered in a great stone pot, as is our way here, and we believe that the spirits of our ancestors come close to us and need our prayers, the prayers in our houses with the smoke of incense rising, and I understood how odd and wonderful the air of this village was now because I came here and married and made this child. The air here was filled with the spirits of Th  o’s coffee farmers and tobacco farmers and woodcutters but also filled with the spirits of my clothiers and newspapermen and bankers, all drawn into this place, into my house, by our incense and our prayers, all brought together by my child, the confluence of families who were, in that invisible realm, astonished to find themselves together.

o’s coffee farmers and tobacco farmers and woodcutters but also filled with the spirits of my clothiers and newspapermen and bankers, all drawn into this place, into my house, by our incense and our prayers, all brought together by my child, the confluence of families who were, in that invisible realm, astonished to find themselves together.

And I said, “Each new year when I was a child, the god of the hearth went to heaven from my house in America. He came to the council of the gods and he said, There are children in this house and they sleep each night in great fear and they have places on their bodies that are the color of the sky in the highlands of Vietnam just after the sun has disappeared. And they pray, even the youngest of them, a boy, for escape and when they love each other, these children, it is to pray that each of the others escapes. And they know that this will happen for them, if at all, one at a time. And this house is empty of incense. And this house sees no spirits in the world.”

And I stopped speaking and the faces in the circle lowered their eyes in deference to me and they understood and they said no more and we all rose and we went away and that night I lay in the dark on a straw mat and my wife lay awake next to me. I could hear her faintly jagged breath and I said, “There was no woman in that life.” And my wife sighed softly and her breathing grew as smooth as her body when I first touched her and I closed my eyes.

Читать дальше

o, Her face was slightly turned to me but her eyes were lowered. I thought, It’s been nearly twenty years since I first lay down with you and touched those places on your body that were smooth and soft and that are coarser now, and I love them still, I love them more for their very coarseness. I do not wish to open the past either, my wife. But this is my village and I was seen across a field by millions and the eyes of that other country turn this way.

o, Her face was slightly turned to me but her eyes were lowered. I thought, It’s been nearly twenty years since I first lay down with you and touched those places on your body that were smooth and soft and that are coarser now, and I love them still, I love them more for their very coarseness. I do not wish to open the past either, my wife. But this is my village and I was seen across a field by millions and the eyes of that other country turn this way.