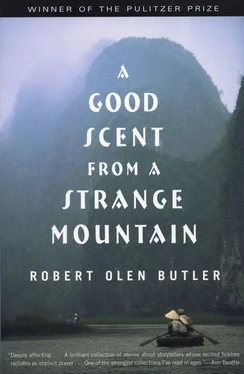

I grew the tobacco myself. That’s what we do in my village. And up here we grow coffee, too. The first time I saw the girl who would be my wife she was by the side of a road spreading the coffee beans out to dry. Spreading them with her bare feet. And when her family finally let me marry her and we lay down at last in our little house — with wood walls and a wood ceiling in this place in Vietnam where there are hardwood trees and cool nights — she rubbed her hands through my hair, calling it sunlight, and I held her feet in my hands and kissed them and they tasted of coffee.

I’m not missing. I’m here. I know the smell of the wood fires and the incense my wife bums for the dead father and mother who gave her to me and the smell of my daughter’s hair washed from the big pot in our backyard to catch the rainwater, and instead, the “USA Today” has got me on the run, waving pitifully across a field at a photographer to put the word out to the world, but they don’t wonder why I’m apparently not smart enough to walk on across that field and say, Take me back to my mama and my papa and my brothers and my sisters who are living ruined lives in America because I’m missing in action. I don’t even have the sense to get close enough to the road so I can be identified, so I’m the lost child of every family in the country with someone whose body was never found.

But I walked away. I just walked away. And there were a thousand of them like me. Two thousand. More, I heard, a lot more. In the back alleys of Saigon, in the little villages in the highlands and along the sea, trying to keep out of the way of the killing just like these people who took us in and didn’t ask any questions.

Though I could see the questions all come back in the faces of my people when the newspaper showed up. We all went out to see it. It’s the way here. The village is small and our elder is Binh and he knew me from the first, he was the first man I saw when I walked in here in 1970 unarmed and bareheaded and I said in the little bit of Vietnamese I had that I was a friend, I wanted to lie down and sleep. He knew what I was doing.

It was yesterday that we sat on mats in front of Tiên’s house and she brought us tea and we looked at the paper.

“It’s you, I think,” Binh said, and he curved his lower lip upward, lifting the little wisp of a H  Chí Minh beard, a beard that he wore not from approval of the man but with a kind of irony.

Chí Minh beard, a beard that he wore not from approval of the man but with a kind of irony.

Tri, who had brought the paper, put it before me again now, and the dozen faces around watched me for the final word. I nodded. Th  o, my wife, touched my shoulder. She could see it, too. “Yes,” I said.

o, my wife, touched my shoulder. She could see it, too. “Yes,” I said.

“What does it say about you?” Binh asked.

“Nothing,” I said. “They don’t know who I am.”

Binh nodded and he did it slow enough that I knew he wanted me to say more. I waited, though, looking away beyond the circle, across the dirt street to the tobacco-drying racks, and some kids were there, two of Tiên’s boys squatting and looking back at me and Tri’s little girl, who stood staring at a dragon head set on a table in the sun. Tiên had been working on the head, repainting the green and red ridges in its face, getting it ready for T  t, the new year. When I looked away from Binh, I thought my daughter, Hoa, might be there, but she wasn’t. And I didn’t want to cast my gaze farther with Binh waiting for me to say more.

t, the new year. When I looked away from Binh, I thought my daughter, Hoa, might be there, but she wasn’t. And I didn’t want to cast my gaze farther with Binh waiting for me to say more.

But I’d waited a little too long already. Binh asked, “Does it speak of some other man?”

“Not one particular man. No. It says some people in America have seen the photo and think it’s proof that Americans are still alive over here, men being held by the communists.”

“MIA,” Binh said, pronouncing each letter with a flat American inflection that he’d picked up from me long ago.

“Yes,” I said.

At this, Binh turned his face, in respect, away from Quang who sat next to him. Quang was almost as old as Binh, clean-shaven, with skin the color of this dirt street moments after a rain. But I glanced at him briefly, and there were others from our little circle who did, too. He was holding the newspaper spread tight in his two hands as if trying to stretch any wrinkles out of it. He was looking at my image there, and I think his mind now was on his own lost son. Most of the people of a certain age in my village have dead children from the war. But Quang’s boy is missing, still, after more than twenty years, and he worries about where the body might be, the spirit lost and hovering around it waiting for rites that would never come.

My village believes in spirits. Last night we all burned incense in our kitchens for the god of the hearth. Such a god lives in each of our houses, and seven days before T  t he goes up to heaven to report on the family. A family is very important in Vietnam. We work and we care for each other and we live under one roof and there is no ending for such a thing. My wife’s mother and father slept on straw mats in our house until the day that each of them died. I will sleep on a straw mat in the house of my daughter until I die. That is my wish.

t he goes up to heaven to report on the family. A family is very important in Vietnam. We work and we care for each other and we live under one roof and there is no ending for such a thing. My wife’s mother and father slept on straw mats in our house until the day that each of them died. I will sleep on a straw mat in the house of my daughter until I die. That is my wish.

Perhaps that’s why I’m so frightened now to see this image of myself in an American newspaper. Why I looked again across to where the children were, more of them now, gathering to watch us and wonder, and I looked for my daughter and I wanted to see her in that moment, a brief glance even. We are meant to protect our families in all their linked parts like we protect our bodies. And the god of the hearth takes special note in his report of how careful we are about that. And how we respect the spirits, the spirits of our family gone to the afterlife before us and the spirits of all the others in the air around us. And we must respect the gods, as well. The minds and wills that animate the universe. Look where they have brought me.

And Hoa appeared. My daughter is tall now, her body changing from a girl to a woman, and her hair is the brown of the dried tobacco, not black but the color of what we grow and prepare here, and I don’t know why I was caught by her hair at that moment but it is long and it has this color that belongs to no one else here, not my wife, not me. And she stepped behind Tri’s daughter and she looked to me, briefly, and then at the little girl staring at the dragon.

Binh still had something on his mind. “Do you think some people in America will look at this picture and remember?”

“There will be many who do that,” I said, and my eyes moved to Quang, and I was thinking of the grief he was drawing from the paper in his hands even then, and Binh knew what I was saying. But I also understood him. He meant: Do you have other people in that past life of yours who will recognize this son or husband or brother of theirs and suffer from this?

I felt my wife stir beside me. She heard this beneath Binh’s words as well, and grew angry at him, I think. It made her fear another woman. I should speak, I knew. But I looked again at Hoa and she was bending to the table and she picked up the dragon head and turned to face Tris daughter and I could see Hoa’s face for a moment there, caught full in the sunlight, and in this light the parts of her body that she had because of me seemed very clear, the highness of her brow, the half-expressed roundness of the lids of her eyes, the length of her nose, the wideness of her mouth, her hair neither dark nor light. And I had a twist of sadness for her, as if she had gotten from me imperfect cells that had made a club foot or an open spine or a weak heart.

Читать дальше

Chí Minh beard, a beard that he wore not from approval of the man but with a kind of irony.

Chí Minh beard, a beard that he wore not from approval of the man but with a kind of irony. o, my wife, touched my shoulder. She could see it, too. “Yes,” I said.

o, my wife, touched my shoulder. She could see it, too. “Yes,” I said. t, the new year. When I looked away from Binh, I thought my daughter, Hoa, might be there, but she wasn’t. And I didn’t want to cast my gaze farther with Binh waiting for me to say more.

t, the new year. When I looked away from Binh, I thought my daughter, Hoa, might be there, but she wasn’t. And I didn’t want to cast my gaze farther with Binh waiting for me to say more.