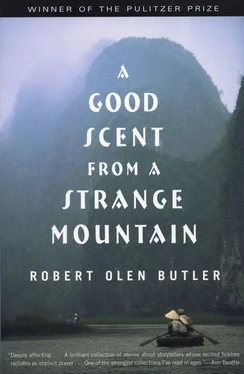

But as I look more closely at these objects and think more clearly, I realize I should not have been surprised at the sentimentality of this American soldier. I am confused in my thinking. His wife was alive. This was the picture of a living person, not a dead ancestor. And whatever excess of sentiment there was in his wanting to see his wife in the jungle each time he stopped to smoke a cigarette, his government had bred such a thing in him — it was their power over him — and I look beyond this smiling woman and there is a sward of blue-green nearby but then the land goes dark and I bend nearer, straining to see, and the darkness becomes earth turned for planting, plowed into even furrows, and I know his family is a family of farmers, his wife smiles at him and her hair is the color of the sunlight that falls on farmers in the early haze of morning and he must have taken as much pleasure from that color as I take from the long drape of night-shadow that my wife combs down for me and the earth must smell strong and sweet, turned like that to grow whatever it is that Americans eat, wheat I think instead of rice, corn perhaps. I am short of breath now and I place my hand on this cigarette pack, covering the woman’s face, and I think the right thing to do is to give these objects over to my government. I have no need for them. And thinking this, I know that I am trying to lie to myself, and I withdraw my hand but I do not look at the face of the wife of the man I killed. I sit back instead and look out my window and I wait.

Perhaps I am waiting for my wife: her approach down the jungle path will make it necessary to put these things away and not consider them again and then I will have no choice but to take them into the authorities in Ðà N  ng when I go, as I do four times a year to report on the continued education of my village. If my wife were to appear right now, even as a pale blue cloud-shadow passes over the path and a dragonfly hovers in the window, if she were to appear in this moment, it would be done, for I have never spoken to my wife about what happened in those years in the jungle and she is a good wife and has never asked me and I would not tempt her by letting her see these objects. But she does not appear. Not in the moment of the blue shadow and the dragonfly and not in the moment afterward as the sunlight returns and the dragonfly rises and hesitates and then dashes away. And I know I am not waiting for my wife, after all. It is something else.

ng when I go, as I do four times a year to report on the continued education of my village. If my wife were to appear right now, even as a pale blue cloud-shadow passes over the path and a dragonfly hovers in the window, if she were to appear in this moment, it would be done, for I have never spoken to my wife about what happened in those years in the jungle and she is a good wife and has never asked me and I would not tempt her by letting her see these objects. But she does not appear. Not in the moment of the blue shadow and the dragonfly and not in the moment afterward as the sunlight returns and the dragonfly rises and hesitates and then dashes away. And I know I am not waiting for my wife, after all. It is something else.

I look again at the face of this woman. The body of her husband was never found. I left him in the clearing and he was far from his comrades and he was far from my thoughts, even after I put his cigarettes in a place to keep them safe. Perhaps she has his name written on a shrine in her home and she lights incense to him and she prays for his spirit. She is the wife of a farmer. Perhaps there is some belief she has that is like the belief of my own wife. But she does not know if her husband is dead or he is not dead. It is difficult to pray in such a circumstance.

And am I myself sentimental now, like the American soldier? I am not. I have earned the right to these thoughts. For instance, there is already something I know of that is inside the cigarette pack. I understood it in a certain way even by the stream. I think on it now and I understand even more. When I shook the cigarette into my hand from the pack, the first one out was small, half-smoked, ragged at the end where he had brushed the burnt ash away to save the half cigarette, and I sensed then and I realize clearly now that this man was a poor man, like me. He could not finish his cigarette, but he did not throw it away. He saved it. There were many half-smoked cigarettes scattered in the jungles of Vietnam by Americans — it was one of the signs of them. American soldiers always had as many cigarettes as they wanted. But this man had the habit of wasting nothing. And I can understand this about him and I can sit and think on it and I can hesitate to give these signs of him away to my government without thinking myself sentimental. After all, this was a man I killed. No thought I have about him, no attachment, however odd, is sentimental if I have killed him. It is earned.

Objects can be very important. We have our flag, red for the revolution, a yellow star for the wholeness of our nation. We have the face of the father of our country, H  Chí Minh, his kindly beard, his steady eyes. And he himself smoked these cigarettes. I turn the pack of Salem over and there is something to understand here. The two bands of color, top and bottom, are color like I sometimes have seen on the South China Sea when the air is still and the water is calm. And the sea is parted here and held within is a band of pure white and this word Salem, and now at last I can see clearly — how thin the line is between ignorance and wisdom — I understand all at once that there is a secret space in the word, not Salem but sa and lem , Vietnamese words, the one meaning to fall and the other to blur, and this is the moment that comes to all of us and this is the moment that I brought to the man who that very morning looked into the face of his wife and smoked and then had to move on and he carefully brushed the burning ash away to save half his cigarette because this farm of his was not a rich farm, he was a poor man who loved his wife and was sent far away by his government, and I was sent by my own government to sit in a tree and watch him move beneath me, frightened, and I brought him to that moment of falling and blurring.

Chí Minh, his kindly beard, his steady eyes. And he himself smoked these cigarettes. I turn the pack of Salem over and there is something to understand here. The two bands of color, top and bottom, are color like I sometimes have seen on the South China Sea when the air is still and the water is calm. And the sea is parted here and held within is a band of pure white and this word Salem, and now at last I can see clearly — how thin the line is between ignorance and wisdom — I understand all at once that there is a secret space in the word, not Salem but sa and lem , Vietnamese words, the one meaning to fall and the other to blur, and this is the moment that comes to all of us and this is the moment that I brought to the man who that very morning looked into the face of his wife and smoked and then had to move on and he carefully brushed the burning ash away to save half his cigarette because this farm of his was not a rich farm, he was a poor man who loved his wife and was sent far away by his government, and I was sent by my own government to sit in a tree and watch him move beneath me, frightened, and I brought him to that moment of falling and blurring.

And I turn the pack of cigarettes over again and I take it into my hand and I gently pull open the cellophane and draw the picture out and she smiles at me now, waiting for some word. I turn the photo over and the back is blank. There is no name here, no words at all. I have nothing but a pack of cigarettes and this nameless face, and I think that they will be of no use anyway, I think that I am a fool of a very mysterious sort either way — to consider saving these things or to consider giving them up — and then I stop thinking altogether and I let my hands move on their own, even as they did on that morning in the clearing, and I shake out the half cigarette into my hand and I put it to my lips and I strike a match and I lift it to the end that he has prepared and I light the cigarette and I draw the smoke inside me. It chills me. I do not believe in ghosts. But I know at once that his wife will go to a place and she will look through many pictures and she will at last see her own face and then she will know what she must know. But I will keep the cigarettes. I will smoke another someday, when I know it is time.

It was me you saw in that photo across a sugarcane field. I was smoking by the edge of the jungle and some French journalist, I think it was, took that photo with a long lens, and you couldn’t even see the cigarette in my hand but you could see my blond hair, even blonder now than when I leaned my rifle against a star apple tree with my unit on up the road in a terrible fight and I put my pack and steel pot beside it and I walked into the trees. My hair got blonder from the sun that even up here in the high-lands crouches on us like a mama-san with her feet flat and going nowhere. Though my hair should’ve gone black, by rights. It should have gone as black as the hair of my wife.

Somebody from the village went into Ðà Lat and came back with an American newspaper that found its way there from Saigon, probably, brought by some Aussie businessman or maybe even an American GI come back to figure out what it was he left over here in Vietnam. There are lots of them come these days, I’m told, the GIs, and it makes things hard for me, worrying about keeping out of their sight. I’ve got nothing to do with them, and that’s why the photo pissed me off. As soon as I saw it, I knew it was me. I knew the field. I knew my own head of hair. And because you can’t see the cigarette, my hand coming down from my face looks like some puny little wave, like I’m saying come help me. And that’s the last goddam thing I want.

Читать дальше

ng when I go, as I do four times a year to report on the continued education of my village. If my wife were to appear right now, even as a pale blue cloud-shadow passes over the path and a dragonfly hovers in the window, if she were to appear in this moment, it would be done, for I have never spoken to my wife about what happened in those years in the jungle and she is a good wife and has never asked me and I would not tempt her by letting her see these objects. But she does not appear. Not in the moment of the blue shadow and the dragonfly and not in the moment afterward as the sunlight returns and the dragonfly rises and hesitates and then dashes away. And I know I am not waiting for my wife, after all. It is something else.

ng when I go, as I do four times a year to report on the continued education of my village. If my wife were to appear right now, even as a pale blue cloud-shadow passes over the path and a dragonfly hovers in the window, if she were to appear in this moment, it would be done, for I have never spoken to my wife about what happened in those years in the jungle and she is a good wife and has never asked me and I would not tempt her by letting her see these objects. But she does not appear. Not in the moment of the blue shadow and the dragonfly and not in the moment afterward as the sunlight returns and the dragonfly rises and hesitates and then dashes away. And I know I am not waiting for my wife, after all. It is something else. Chí Minh, his kindly beard, his steady eyes. And he himself smoked these cigarettes. I turn the pack of Salem over and there is something to understand here. The two bands of color, top and bottom, are color like I sometimes have seen on the South China Sea when the air is still and the water is calm. And the sea is parted here and held within is a band of pure white and this word Salem, and now at last I can see clearly — how thin the line is between ignorance and wisdom — I understand all at once that there is a secret space in the word, not Salem but sa and lem , Vietnamese words, the one meaning to fall and the other to blur, and this is the moment that comes to all of us and this is the moment that I brought to the man who that very morning looked into the face of his wife and smoked and then had to move on and he carefully brushed the burning ash away to save half his cigarette because this farm of his was not a rich farm, he was a poor man who loved his wife and was sent far away by his government, and I was sent by my own government to sit in a tree and watch him move beneath me, frightened, and I brought him to that moment of falling and blurring.

Chí Minh, his kindly beard, his steady eyes. And he himself smoked these cigarettes. I turn the pack of Salem over and there is something to understand here. The two bands of color, top and bottom, are color like I sometimes have seen on the South China Sea when the air is still and the water is calm. And the sea is parted here and held within is a band of pure white and this word Salem, and now at last I can see clearly — how thin the line is between ignorance and wisdom — I understand all at once that there is a secret space in the word, not Salem but sa and lem , Vietnamese words, the one meaning to fall and the other to blur, and this is the moment that comes to all of us and this is the moment that I brought to the man who that very morning looked into the face of his wife and smoked and then had to move on and he carefully brushed the burning ash away to save half his cigarette because this farm of his was not a rich farm, he was a poor man who loved his wife and was sent far away by his government, and I was sent by my own government to sit in a tree and watch him move beneath me, frightened, and I brought him to that moment of falling and blurring.