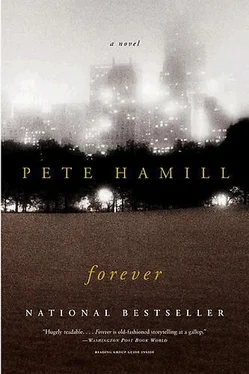

Pete Hamill - Forever

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Forever» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, ISBN: 2008, Издательство: Paw Prints, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Forever

- Автор:

- Издательство:Paw Prints

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:9781435298644

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Forever: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Forever»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Reprint. 100,000 first printing.

Forever — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Forever», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then, on a Tuesday morning in June, Cormac heard a tale from a Nassau Street barber. He lived on Cherry Street. The night before, a neighbor named Fitzgerald came home from work as a tailor, and within an hour was simultaneously puking and shitting and bending over with cramps. He went quiet for a while, then groaned with headache, laughed in a giddy way, then drowsed in a jittery slumber. He jerked awake and vomited, heaving hunks of undigested food upon the floor, and then hacked up phlegm that was sticky and glistening in the candlelight. He screamed in thirst: “Water, give me cold water.” His eyes went dull as lead, and his face turned pale blue and his eyes and mouth and skin pinched in tightly and the skin of his hands and feet grew as dark and wrinkled as a prune. And then the body shuddered and the man was very still and quite dead. Five hours after the first symptoms.

Hearing this account, Cormac reached for his copy of Boccaccio. In The Decameron, the good doctor had wondered in the fourteenth century as the Black Death raged in Florence how many gallant gentlemen, fair ladies, and sprightly youths, “having breakfasted in the morning with their kinsfolk, acquaintances and friends, supped that same evening with their ancestors in the next world!”

Cormac rushed to see Bryant, waited an hour while the editor chatted with some visiting politician, and, after citing Boccaccio as a way to get Bryant’s attention, explained what he’d been told by the barber. Bryant then was in his early thirties, with a sharp nose and piercing eyes, and was not yet encased in the pomposity that all would remember later. Bryant listened, his eyes narrowing, and whispered, “Good God, it’s the cholera.”

Bryant sent Cormac to the City Hall for more information, but nobody would confirm or deny what had clearly happened on Cherry Street. Back in the office, Bryant told him to wait. To write nothing. To wait for more facts. Above all, to avoid spreading panic. That night Cormac’s friend the barber died, along with his mother, aunt, and oldest child.

They became numbers, as first two died each day, and then twenty, and then the epidemic could no longer be hidden. Too late, the Council began to clear the pestilential mounds of infested garbage. Too late, the slum buildings were emptied and scoured and whitewashed. Old women awoke one stinking morning and then fell back dead. Infants died. Children died. One of Cormac’s friends died, a fine African musician named Michael George; he might have become one of the first great American composers and became instead a corpse at twenty-nine.

As in all plagues, as in Boccaccio, as in Daniel Defoe, all manner of quack and charlatan appeared with cures they were happy to sell. Opium was peddled openly as a curative, along with laudanum, and cayenne pepper, and camphor and calomel. Doctors offered bleedings. People drank salt or mustard, hot punch and hartshorn, or enveloped themselves in tobacco smoke. They still died. The God Cure revived for a week or so, with bellowed pious demands for prayer and fasting and repentance. But then the preachers joined the rich in the flight to the countryside, leaving the souls of the poor to the personal judgment of God. As always, the dead and the dying were blamed for their own fate. Many were Irish, and Cormac heard them condemned by the rich as their carriages trotted away to safety. A filthy lot, the Irish (said one perfumed auctioneer). Papists too. Animals as low as the pigs and rats. In the empty streets at night, Cormac could hear wailing songs in Irish (for many could not speak English) and garbled prayers and the jerking sounds of horror at still another death. Many must have imagined the consolations of the Otherworld or the Christian Heaven. Hundreds died.

Sales of all newspapers fell as their rich readers departed and the illiterate immigrants were left behind. Advertising ceased, for few shops were open. The South Street waterfront was deserted, the streets empty day and night, crews and captains refusing to enter the infected port. There were theories for a few days in the Evening Post about diet being the cause of the deaths. But meat-eaters died in the same streets as vegetarians. Cranks who ate only nuts and grains (while chanting Iroquois prayers) fell as if axed. A week later, the drastic New York weather was blamed. But they died on dry days and damp, in the hammering heat of noon and at the black midnight hour, calling at all hours for water, cold water. The poor died most of all, but so did the favorite daughter of John Jacob Astor in flight to Europe. Shit collectors died and so did insurance peddlers. Some of the infected grew mad after the first symptoms struck and lurched into the streets and reached for strangers to give them the infection, as if insisting they would not go alone on the swift journey to Heaven or Hell. There were many brave doctors who obeyed their oaths, but even they were hampered by much ignorance and not enough hospitals. The cholera is, said one, and that is all we know . New York Hospital slammed its doors to the dying and the new Bellevue, a combination of hospital and almshouse, was transformed into a vast filthy limbo. Nurses died. Doctors died. Too many churches slammed shut their doors too, the clergymen bolting them before departing. Policemen were assigned to the abandoned churches and the empty houses of the rich to prevent looting, but soon they too were gone, fleeing the city or buried in its crowded trenches.

As he had been in the yellow fever epidemics, Cormac discovered he was immune. An immunity to yellow fever could be traced to African blood, to Kongo. Cholera was another matter. But as he roamed among the dead and dying, gathering facts that were written with haste and anger on foolscap but never appeared in the newspaper, or trying to comfort the afflicted with useless words, part of him longed to be taken by the cholera. If this was life, he did not want it. Until that summer, he had never thought such things. Now they came to him almost every day. Life, in this season, was about shit and death.

To keep from thinking, he wrote many stories for the Evening Post while Bryant and his most favored editor, William Leggett, gathered their families together across the Hudson in Hoboken and found shelter from the storm. At last, some stories made their way into the newspaper. Stories about water and corruption. Stories that told people where to go for help but offered no easy hope. Cormac hoped that a person who could read would tell ten persons who could not. He hoped thousands would demand water.

Cormac was ignorant of the causes of the cholera but knew that it wasn’t the Irish (blamed as the Jews were blamed for the Black Death) and knew it wasn’t something as vague as the miasma. Whatever it was, science would discover the cause. He was convinced that the cure would come from water, cold water.

Finally it ended. After nine terrifying weeks. And three thousand five hundred and twenty-six known deaths. The rich slowly returned, sending in their African or Irish servants as the advance patrols, like canaries into a coal mine. Bryant and Leggett returned too, and Cormac urged them to start a crusade in the Evening Post, demanding that the city obtain a big, strong, muscular supply of clean water. They nodded, they listened, they thanked him, they published a few polite editorials.

New York got no clean water.

The miasma returned with the people.

The cholera returned in 1833.

Shit and filth got worse.

The cholera returned in 1834.

All that dying passed through him again as he went home after sundown on his birthday, September 9, 1834. The flat was an oven. He opened the windows, removed his tie and shirt, pulled off his shoes. He sat in a chair, very still, gazing at his books and paintings, at the pots of color and the clean brushes. But his skin was crawling. The room filled with the stink of his feet and his armpits and his balls. He scratched at his skin, which felt as if millions of insects were crawling under the surface. He scratched at his hair. He dipped a cloth into the bowl of water and scrubbed his armpits, feet, and balls. The stench did not leave.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Forever»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Forever» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Forever» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.