© Matt Kent

CONTENTS

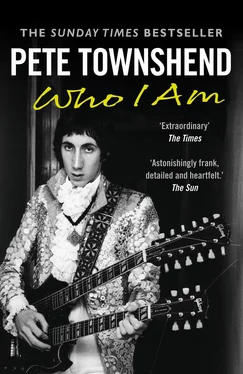

COVER

TITLE PAGE © Matt Kent

ACT ONE: WAR MUSIC ACT ONE WAR MUSIC You didn’t hear it. You didn’t see it. You won’t say nothing to no one. Never tell a soul What you know is the truth ‘1921’ (1969) Don’t cry Don’t raise your eye It’s only teenage wasteland ‘Baba O’Riley’ (1971) And I’m sure – I’ll never know war ‘I’ve Known No War’ (1983)

1. I WAS THERE

2. IT’S A BOY!

3. YOU DIDN’T SEE IT

4. A TEENAGE KIND OF VENGEANCE

5. THE DETOURS

6. THE WHO

7. I CAN’T EXPLAIN

8. SUBSTITOOT

9. ACID IN THE AIR

10. GOD CHECKS IN TO A HOLIDAY INN

11. AMAZING JOURNEY

12. TOMMY: THE MYTHS, THE MUSIC, THE MUD

ACT TWO: A REALLY DESPERATE MAN

13. LIFEHOUSE AND LONELINESS

14. THE LAND BETWEEN

15. CARRIERS

16. A BEGGAR, A HYPOCRITE

17. BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU PRAY FOR

18. THE UNDERTAKER

19. GROWING INTO MY SKIN

20. ROCK STAR FUCKUP

ACT THREE: PLAYING TO THE GODS

21. THE LAST DRINK

22. STILL LOONY

23. IRON MAN

24. PSYCHODERELICT

25. RELAPSE

26. NOODLING

27. A NEW HOME

28. LETTER TO MY EIGHT-YEAR-OLD SELF

29. BLACK DAYS, WHITE KNIGHTS

30. TRILBY’S PIANO

31. INTERMEZZO

32. WHO I AM

PICTURE SECTION

APPENDIX: A FAN LETTER FROM 1967

CODA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AFTERWORD

LIST OF SEARCHABLE TERMS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ACT ONE

WAR MUSIC

You didn’t hear it. You didn’t see it. You won’t say nothing to no one. Never tell a soul What you know is the truth

‘1921’ (1969)

Don’t cry Don’t raise your eye It’s only teenage wasteland

‘Baba O’Riley’ (1971)

And I’m sure – I’ll never know war

‘I’ve Known No War’ (1983)

1 I WAS THERE

It’s extraordinary, magical, surreal, watching them all dance to my feedback guitar solos; in the audience my art-school chums stand straight-backed among the slouching West and North London Mods, that army of teenagers who have arrived astride their fabulous scooters in short hair and good shoes, hopped up on pills. I can’t speak for what’s in the heads of my fellow bandmates, Roger Daltrey, Keith Moon or John Entwistle. Usually I’d be feeling like a loner, even in the middle of the band, but tonight, in June 1964, at The Who’s first show at the Railway Hotel in Harrow, West London, I am invincible.

We’re playing R&B: ‘Smokestack Lightning’, ‘I’m a Man’, ‘Road Runner’ and other heavy classics. I scrape the howling Rickenbacker guitar up and down my microphone stand, then flip the special switch I recently fitted so the guitar sputters and sprays the front row with bullets of sound. I violently thrust my guitar into the air – and feel a terrible shudder as the sound goes from a roar to a rattling growl; I look up to see my guitar’s broken head as I pull it away from the hole I’ve punched in the low ceiling.

It is at this moment that I make a split-second decision – and in a mad frenzy I thrust the damaged guitar up into the ceiling over and over again. What had been a clean break becomes a splintered mess. I hold the guitar up to the crowd triumphantly. I haven’t smashed it: I’ve sculpted it for them. I throw the shattered guitar carelessly to the ground, pick up my brand-new Rickenbacker twelve-string and continue the show.

That Tuesday night I stumbled upon something more powerful than words, far more emotive than my white-boy attempts to play the blues. And in response I received the full-throated salute of the crowd. A week or so later, at the same venue, I ran out of guitars and toppled the stack of Marshall amplifiers. Not one to be upstaged, our drummer Keith Moon joined in by kicking over his drumkit. Roger started to scrape his microphone on Keith’s cracked cymbals. Some people viewed the destruction as a gimmick, but I knew the world was changing, and a message was being conveyed. The old, conventional way of making music would never be the same.

I had no idea what the first smashing of my guitar would lead to, but I had a good idea where it all came from. As the son of a clarinettist and saxophonist in the Squadronaires, the prototypical British Swing band, I had been nourished by my love for that music, a love I would betray for a new passion: rock ’n’ roll, the music that came to destroy it.

I am British. I am a Londoner. I was born in West London just as the devastating Second World War came to a close. As a working artist I have been significantly shaped by these three facts, just as the lives of my grandparents and parents were shaped by the darkness of war. I was brought up in a period when war still cast shadows, though in my life the weather changed so rapidly it was impossible to know what was in store. War had been a real threat or a fact for three generations of my family.

In 1945 popular music had a serious purpose: to defy postwar depression and revitalise the romantic and hopeful aspirations of an exhausted people. My infancy was steeped in awareness of the mystery and romance of my father’s music, which was so important to him and Mum that it seemed the centre of the universe. There was laughter and optimism; the war was over. The music Dad played was called Swing. It was what people wanted to hear. I was there.

2 IT’S A BOY!

I have just been born, war is over, but not completely.

‘It’s a boy!’ someone shouts from the footlights. But my father keeps on playing.

I am a war baby though I have never known war, born into a family of musicians on 19 May 1945, two weeks after VE Day and four months before VJ Day bring the Second World War to an end. Yet war and its syncopated echoes – the klaxons and saxophones, the big bands and bomb shelters, V2s and violins, clarinets and Messerschmitts, mood-indigo lullabies and satin-doll serenades, the wails, strafes, sirens, booms and blasts – carouse, waltz and unsettle me while I am still in my mother’s womb.

Two memories linger for ever like dreams that, once remembered, are never forgotten.

I am two years old, riding on the top deck of an old tram that Mum and I have boarded at the top of Acton Hill in West London. The tram trundles past my future: the electrical shop where Dad’s first record will go on sale in 1955; the police station where I’ll go to retrieve my stolen bike; the hardware store that mesmerises me with its thousands of perfectly labelled drawers; the Odeon where I will attend riotous Saturday movie matinées with my pals; St Mary’s Church where years from now I sing Anglican hymns in the choir and watch hundreds of people take communion, but never do so myself; the White Hart pub where I first get properly drunk in 1962 after playing a regular weekly gig with a school rock band called The Detours, that will one day evolve into The Who.

I am a little older now, my second birthday three months past. It’s the summer of 1947 and I’m on a beach in bright sunshine. I’m still too young to run around, but I sit up on the blanket enjoying the smells and sounds: sea air, sand, a light wind, waves murmuring against the shore. My parents ride up like Arabs on horseback, spraying sand everywhere, wave happily, and then ride off again. They are young, glamorous, beautiful, and their disappearance is like the challenge of an elusive grail.

Dad’s father, Horace Townshend (known as Horry), was prematurely bald at thirty, but still striking with his aquiline profile and thick-rimmed glasses. Horry, a semi-professional musician/composer, wrote songs and performed in summer entertainments at seasides, parks and music halls during the 1920s. A trained flautist, he could read and write music, but he liked the easy life and never made much money.

Читать дальше