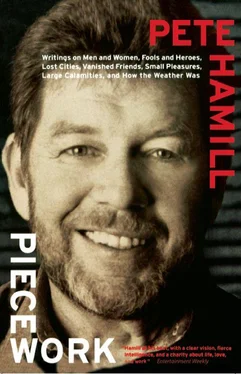

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I guess it lasted for a couple of reasons,” Gleason says. “One, the show was funny. That usually helps. Two, you like the people. If the audience likes you, you’re home free.”

The show was also a triumph of show-business craft. Gleason, with his producer, Jack Philbin, and his crew of writers (Walter Stone, Marvin Marx, Herbert Finn, and others), evolved rules for The Honeymooners that contributed to the show’s durability. “First, it had to be believable,” Gleason says. “Whatever the deal was, you had to believe it could happen. Second, the audience had to know what’s really going on before Ralph does. That was the key to the comedy.”

In addition, each show was classically constructed, with a beginning, middle, and end (“I see stuff now that stops, but doesn’t really end”). The situations were quickly, carefully, and lucidly set up, the characters were clearly defined, and the relationships were held together by a rough kind of love. Ralph really did believe that Alice was the greatest (he would never ever really try to send her to the moon with a haymaker). Alice loved Ralph in the most confident way, unafraid to slam into him, completely aware of his flaws and faults, his insecurities, his boastfulness, his wild-eyed schemes, but equally clear about his strengths, the most important of which was a heart as big as Bensonhurst. They had no kids (except Ralph), a fact that made the relationship more modern than those in most of the kid-littered sitcoms that first showed up in the fifties. And, of course, Ralph and Norton loved each other, too, without ever stating what they felt. They were as dependent upon each other as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, whom Ralph, the dreamer, and Norton, the practical man, resemble in other ways.

In his 1956 biography of Gleason, The Golden Ham, Jim Bishop reconstructed the story conference that led to the invention of The Honeymooners:

One afternoon Joe Bigelow and Harry Crane were trying to write a sketch with the star, and Gleason said that he had an idea for a sketch that would revolve around a married couple — a quiet shrewd wife and a loudmouthed husband.

“You got a title for it?” asked Bigelow.

“Wait a minute,” said Crane. “How about The Beast’?”

Jackie got to his feet. “Just a second,” he said. “I always wanted to do this thing, and the man isn’t a beast. The guy really loves this broad. They fight, sure. But they always end in a clinch.”

Bigelow shrugged. “It could be a thing.”

“I come from a neighborhood full of that stuff. By the time I was fifteen, I knew every insult in the book.”

“Then let’s try it,” said Bigelow.

“But not The Beast,’ “ said Jackie. “That’s not the title.”

“Why not?”

“It sounds like the husband is doing all the fighting. We need something a little left-handed as a title. You know, this kind of thing can go and go and go.”

“How about The Lovers,’ “ said Harry Crane.

“That’s a little closer, Harry.” Gleason paced the floor. “A little closer, but it could mean that they’re not married. We need something that tells at once that they’re married.”

” The Couple Next Door’?”

“No. How about The Honeymooners’?”

That was it, and, like a great novelist, Gleason reached back into the early years of his life for his characters. They’re still with us; they’re still with Gleason.

“I knew a lot of guys like Ralph,” he says now, “back there, growing up.”

In William Hazlitt’s Lectures on the English Comic Writers, written in the winter of 1818, there’s a line that’s true of all of us but seems particularly appropriate to Gleason: “To understand or define the ludicrous, we must first know what the serious is.” The serious roots of Gleason’s talent go back to the Brooklyn of his childhood, specifically to Bushwick, which was then an Irish and Italian working-class district.

“Everything happened there,” Gleason says. “Everything.”

He was born Herbert John Gleason on February 26, 1916, the second child of Herbert Gleason and Mae Kelly. There was a brother eleven years older than Jackie; his name was Clemence, and he died when Jackie was three. Though Jackie has no memory of him, he took his dead brother’s name at confirmation. His father, slim, black-haired, a drinker, worked in the Death Claims Department of the Mutual Life Insurance Company at 20 Nassau Street.

“He had beautiful Spencerian handwriting,” Gleason remembers. “And he would fill in the policies with the names. I remember him sometimes doing the work at night at the kitchen table.”

Herbert Gleason was paid $35 a week; he sold candy bars on the side. The family moved all around Bushwick, living on Herkimer Street and Somers Street, Bedford Avenue and Marion Street. But young Jackie stayed in the same school, P.S. 73. And he went to the same church, Our Lady of Lourdes. The Gleasons settled at last in the third-floor-right apartment at 358 Chauncey Street, the street where, many years later, Ralph and Alice, Norton and Trixie were to establish permanent residence.

On Friday, December 15,1925, at ten minutes after noon, Herbert Gleason took his hat, his coat, and his paycheck, left the offices of the insurance company, and was never seen again. The night before, he had destroyed all the family pictures in which he appeared. When Mae Gleason realized that he was not coming back, she took a job as a change clerk in the Lorimer Street station of the BMT. And Jackie started his education on the streets. He was a member of a gang called the Nomads, hung around Schuman’s candy store and Freitag’s Delicatessen’s (as it was pronounced). He went dancing at the Arcadia when he had money, and he learned to shoot pool. About his father, years later, Gleason said, “He was as good a father as I’ve ever known.” But his father did leave him with something: a vision.

“My father took me to the Halsey Theatre, a real dump, a classic,” he says. The Halsey featured a daily movie and five acts of vaudeville. “We sat way down front, in the first row. I’d never seen this before, guys coming out and saying funny things, getting laughs. And for some reason, at some point, I stood up and looked out over the audience. That was the moment. I knew I wanted to be like that, facing an audience, the audience facing me. I knew I wanted to do that.”

It was a while before he faced an audience again. After his father left, Jackie started hanging out in Joe Corso’s Poolroom One Flight Up (“That was the whole name”). He went there with his friend Carmine Pucci, and when they won at pool, they’d buy cheap wine or “loosies” (individual cigarettes). “I was a rack boy when I was ten, and hustling guys already. Graduation day was always the best. On graduation day, everybody’d get these gold pins. And I’d play them for their gold pins. Then I’d take the pins to the hockshop and get maybe $20, and nobody ever asked what a ten-year-old kid was doing with all these gold pins.”

When he graduated from P.S. 73, he talked himself into the school play, doing a recital of “Little Red Riding Hood” in a Yiddish accent that tore up the place, and then went on to John Adams High School, supposedly for “vocational training.” He never finished the first year, and moved on to his true school: the streets.

“For a while, I worked as an exhibition diver for a guy named Chester Billy: He was the star and the rest of us did all the funny stuff. We had this portable tank that was six feet deep. They greased the bottom so when you dove in you slid right up. The bottom was terrible, disgusting; it stunk of grease. They would fold up the tank after the show with the grease still in it. And all the girls in the show had green hair from the chlorine.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.