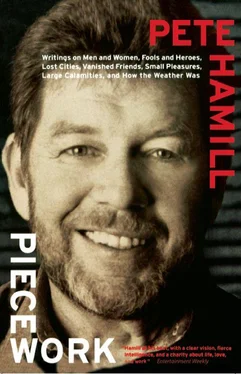

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But when the crunch came two weeks later, Sinatra chose not to fight the revocation order. Apparently his friendship with Giancana was more important than his investment in Nevada, and he sold his interests for $3.5 million. In 1975 Giancana was shot to death in the basement of his Chicago home. Phyllis McGuire went to the funeral, but Sinatra didn’t. Sinatra is again trying to get a gambling license in Nevada.

“It’s ridiculous to think Sinatra’s in the mob,” said one New Yorker who has watched gangsters collect around Sinatra for more than 30 years. “He’s too visible. He’s too hot. But he likes them. He thinks they’re funny. In some way he admires them. For him it’s like they were characters in some movie.”

That might be the key. Some people who know Sinatra believe that his attraction to gangsters — and their attraction to him — is sheer romanticism. The year that Sinatra was fifteen, Hollywood released W. R. Burnett’s Little Caesar; more than 50 gangster films followed in the next eighteen months. And their view of gangsters was decidedly romantic: The hoodlums weren’t cretins peddling heroin to children; they were Robin Hoods defying the unjust laws of Prohibition. Robert Warshow defined the type in his essay “The Gangster as Tragic Hero”:

The gangster is the man of the city, with the city’s language and knowledge, with its queer and dishonest skills and its terrible daring, carrying his life in his hands like a placard, like a club. For everyone else, there is at least the theoretical possibility of another world — in that happier American culture which the gangster denies, the city does not really exist; it is only a more crowded and more brightly lit country — but for the gangster there is only the city; he must inhabit it in order to personify it: the real city, but that dangerous and sad city of the imagination which is so much more important, which is the modern world.

That is almost a perfect description of Frank Sinatra, who still carries his life in his hands like a placard, or like a club. His novel might be a very simple one indeed: a symmetrical story about life imitating art.

III.

“My son is like me. You cross him, he never forgets.”

— Dolly SinatraSomewhere deep within Frank Sinatra, there must still exist a scared little boy. He is standing alone on a street in Hoboken. His parents are nowhere to be seen. His father, Anthony Martin, is probably at the bar he runs when he is not working for the fire department; the father is a blue-eyed Sicilian, close-mouthed, passive, and, in his own way, tough. He once boxed as “Marty O’Brien” in the years when the Irish ran northern New Jersey. The boy’s mother, Natalie, is not around either. The neighbors call her Dolly, and she sometimes works at the bar, which was bought with a loan from her mother, Rosa Garaventi, who runs a grocery store. Dolly Sinatra is also a Democratic ward leader. She has places to go, duties to perform, favors to deny or dispense. She has little time for traditional maternal duties. And besides, she didn’t want a boy anyway.

“I wanted a girl and bought a lot of pink clothes,” she once said. “When Frank was born, I didn’t care. I dressed him in pink anyway. Later, I got my mother to make him Lord Fauntleroy suits.”

Did the other kids laugh at the boy in the Lord Fauntleroy suits? Probably. It was a tough, working-class neighborhood. Working-class. Not poor. His mother, born in Genoa, raised in Hoboken, believed in work and education. When she wasn’t around, the boy was taken care of by his grandmother Garaventi, or by Mrs. Goldberg, who lived on the block. “I’ll never forget that kid,” a neighbor said, “leaning against his grandmother’s front door, staring into space. …”

Later the press agents would try to pass him off as a slum kid. Perhaps the most important thing to know about him is that he was an only child. Of Italian parents. And they spoiled him. From the beginning, the only child had money. He had a charge account at a local department store and a wardrobe so fancy that his friends called him “Slacksey.” He had a secondhand car at fifteen. And in the depths of the Depression, after dropping out of high school, he had the ultimate luxury: a job unloading trucks at the Jersey Observer.

Such things were not enough; the boy also had fancy dreams. And the parents didn’t approve. When he told his mother that he wanted to be a singer, she threw a shoe at him. “In your teens,” he said later, “there’s always someone to spit on your dreams.” Still, the only child got what he wanted; eventually his mother bought him a $65 portable public-address system, complete with loudspeaker and microphone. She thus gave him his musical instrument and his life.

She also gave him some of her values. At home she dominated his father; in the streets she dominated the neighborhood through the uses of Democratic patronage. From adolescence on, Sinatra understood patronage. He could give his friends clothes, passes to Palisades Park, rides in his car, and they could give him friendship and loyalty. Power was all. And that insight lifted him above so many other talented performers of his generation. Vic Damone might have better pipes, Tony Bennett a more certain musical taste, but Sinatra had power.

Power attracts and repels; it functions as aphrodisiac and blackjack. Men of power recognize it in others; Sinatra has spent time with Franklin Roosevelt, Adlai Stevenson, Jack Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Spiro Agnew, Walter Annenberg, Hugh Carey, Ronald Reagan; all wanted his approval, and he wanted, and obtained, theirs. He could raise millions for them at fund raisers; they would always take his calls. And the politicians had a lot of company. On the stage at Caesars Palace, or at an elegant East Side dinner party, Sinatra emanates power. Certainly the dark side of the legend accounts for some of that effect; the myth of the Mafia, after all, is not a myth of evil, but a myth of power.

But talent is essential, too. During the period of The Fall, when he had lost his voice, he panicked; he could accept anything except impotence. Without power he is returned to Monroe Street in Hobo-ken, a scared kid. That kid wants to be accepted by powerful men, so he shakes hands with the men of the mob. But the scared kid also understands loneliness, and he uses that knowledge as the engine of his talent. When he sings a ballad — listen again to “I’m a Fool to Want You,” recorded at the depths of his anguish over Ava Gardner — his voice haunts, explores, suffers. Then, in up-tempo songs, it celebrates, it says that the worst can be put behind you, there is always another woman and another bright morning. The scared kid, easy in the world of women and power, also carries the scars of rejection. His mother was too busy. His father sent him away.

“He told me, ‘Get out of the house and get a job,’ “ he said about his father in a rare TV interview with Bill Boggs a few years ago. “I was shocked. I didn’t know where the hell to go. I remember the moment. We were having breakfast.…This particular morning my father said to me, ‘Why don’t you get out of the house and go out on your own?’ What he really said was ‘Get out.’ And I think the egg was stuck in there about twenty minutes, and I couldn’t swallow it or get rid of it, in any way. My mother, of course, was nearly in tears, but we agreed that it might be a good thing, and then I packed up a small case that I had and came to New York.”

He came to New York, all right, and to all the great cities of the world. The scared kid, the only child, invented someone named Frank Sinatra and it was the greatest role he ever played. In some odd way he has become the role. There is a note of farewell in his recent performances. One gets the sense that he is now building his own mausoleum.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.