Early in the morning, a nurse gave me some pills; another injected me with some nameless drug; a man who looked like John Coltrane shaved my chest and pubic hair. My wife looked concerned. I made some bad jokes as they moved me onto a gurney. I made a few more on the way down the hall. Then I thought this was a kind of dumb Ronald Reagan act and shut up. I kissed my wife’s hand. They wheeled me into the operating room. They placed something over my face and I was gone.

From that long, drugged morning, I remember only a vision of Cardinal O’Connor in a gray sweat shirt, playing handball at one of those Coney Island courts that seem to have been painted by Ben Shahn. The good cardinal was sweating hard, great dark blotches staining his shirt, and he said nothing as he batted the small black ball against the unyielding wall. I’m not a religious man and don’t know O’Connor, but his cameo appearance in my delirium certainly cheered me up. I was suddenly awake. My wife smiled and kissed me. There were feeding tubes in my arms, two tubes draining my slashed lung, other tubes carrying away wastes. And I hurt. Oh, yeah, I hurt. Not a sharp, stabbing pain. It was more generalized, as if some giant had lifted me up and then slammed me viciously to the ground. This was not a trip to the beach. I hurt. I fucking well hurt.

“Not cancer,” my wife whispered. “Tu-ber-cu-lo-sis. …”

I have a memory of someone shouting, “Not cancer! Not cancer!” while I was under. But I don’t trust that memory as a fact. I must have invented it later. I remember nothing of my time on the operating table, although I was there for more than three hours, with another four in intensive care. The surgeon made an incision from under my right pectoral muscle across my back. About twelve inches long. He cut delicately into the lung and found the Thing. Then they all waited while it was analyzed.

And it wasn’t cancer.

The nodule, shaped like a tiny Cheerio, was a necrotizing granuloma, caused by tuberculosis. It was not contagious, being already dead. They sewed me up.

I smiled (she told me) and fell asleep. Later I would talk to friends about the epidemic of TB that is moving through American cities, passed along by our derelict armies. “They cough,” the doctor told me, “and twenty minutes later you can walk through it, and-…” Later, I would make jokes with visitors and eat ice cream and smell the great garlands of arriving flowers. A lovely nurse from Haiti would wash me, soaping my face, arms, genitals — a Catherine Barkley without the sentimentality — but every last erotic impulse, alas, was erased by pain. After midnight, the man in the next bed ripped at the trache in his throat, the strangled sounds (uh, uh, uh, uh, uh, uh, uh) rose from him in agonized protest while his wife screamed at him in Yiddish. Later, I would at last have my ’60s experience all in one night, drugs lifting this old whiskey drinker into distended bands of time and color and sound while the words of friends and strangers mixed together in the slippery mist of a ruptured consciousness.

But for that long moment, coming back from the anesthetized emptiness, those two words seemed the most lucid and important of all.

Not cancer.

“Not cancer,” my wife said again.

“Hand me the dice,” I said.

ESQUIRE,

January 1991

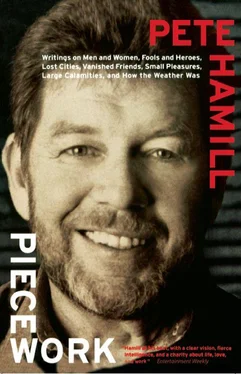

New York journalist Pete Hamill is among the last of a dying breed: the old-school generalist who writes about anything and everything, guided only by passionate and boundless curiosity. In this collection of his finest writings since 1970, Hamill tackles such diverse subjects as what television and crack have in common, how Mike Tyson spent his time in prison, and what it’s like to realize you’re middle-aged—not to mention Octavio Paz, Brooklyn’s Seventh Avenue, Frank Sinatra, American immigration policy, Northern Ireland, and Madonna. Piecework is Hamill at his very best.

“The perfect sampler…Infused with clear-headed prose that searches out the bright lights and blind spots of the human heart.”

— People

“Pete Hamill, who has been around the block a few dozen times and has the scars to prove it, works a lot of territory. He talks to people, checks the sound, the smell, and the feel of places, and writes with a wonderful, sharp honesty.”

— Providence Journal-Bulletin

“Hamill’s words reach out from the page and prick holes in your prejudices, question your beliefs and cajole, yet they also have the power to touch you deeply.”

— Associated Press

Pete Hamill started his career at the New York Post in 1960. He has written for numerous national magazines, has worked as a syndicated columnist, and is currently editor in chief of the New York Daily News . His books include eight novels, among them the recently published Snow in August ; two collections of stories; and A Drinking Life , his bestselling memoir.