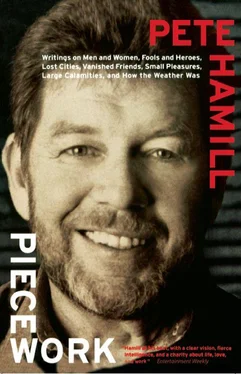

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Three years ago, I awoke with a terrible pain in my left shoulder; the day before, I had been lifting free weights just to see what I could do; I was sure I had merely pulled a muscle. But the pain went on for months, ruining sleep, aching at all hours. I assumed comical positions in bed, searching for stillness. I found myself unable to pitch quarters into the receptacles at toll booths. I thought: I might live the rest of my life with this pain. I was wrong, of course; the pain was cured with a few shots of cortisone. But the hard, invincible body I thought I possessed when young is gone.

Sometimes I hear my own labored breathing and instantly remember the emphysemic sounds of my father’s final years. Fifteen years ago I discovered with alarm that I could not read a Scoreboard without glasses; now I don spectacles to watch the evening news. In my twenties, I once worked seventy-three hours straight without sleep, belting down waterfalls of coffee, smoking too many cigarettes, listening through the nighttime hours to Symphony Sid. What I then lacked in craft I made up for with energy. Now I take naps in the afternoon. I have been a fortunate man, free of diseases, with few physical injuries. But now I go each year for the physical examination by the doctor and dread the first appearance of blood in the stool or the spot on the X ray.

Some of the minor warning signs are mental. I cannot, for example, remember any additional names or numbers. I am introduced to a stranger at a dinner party and the new name breaks into letters and flies around the room like dead leaves in an autumn wind. In the past year, I have moved with my wife into a small city apartment and a house in the country; I must carry the telephone numbers and the zip codes in my wallet. Once I hauled around in my head the batting averages of entire baseball teams; now I must search them out each day in the newspaper. My memory of the days and nights of my youth remains fine; it is last year that is a blur. It’s as if one of the directories in my brain has reached its full capacity and will accept no more bytes.

None of these small events is original to me, of course. I’m aware that some variation of them has happened to all aging human beings from the beginning of time. As a reporter I’ve witnessed much of the grief of other human beings, the astonishing variety of their final days. And I knew, watching my father get old and then die, that aging was inevitable; it had happened to him, and I’d seen it happen to my friends. Still, it was a cause of some wonder to undergo changes that had not been willed, that hadn’t enlisted my personal collaboration.

To acknowledge the inevitability of death, however, is not to fear it. I was more afraid of death at thirty-five than I am now. My night thoughts that year were haunted by visions of the sudden end of my life. Images of violence, carried over from my work as a reporter, roamed freely through my dreams. Before sleep, I would act out imaginary struggles with the knife-wielding intruder who was somewhere out in those shadowed streets. I did a lot of drinking that year. I slept too often with the light on.

In middle age, I recognize that most of my fear at thirty-five came from a sense of incompletion. That age is a more critical one for American men than is fifty, because the majority of us have grown up obsessed with sports. At thirty-five, a third baseman is an aged veteran, a football player has been trampled into retirement, a prizefighter is tending bar somewhere, wearing ridges of old scar tissue as the sad ornaments of his trade.

But at thirty-five, I often felt as if I was only beginning to live (and of course I was right). I wanted more time, and the prospect of death filled me with panic. There were still too many books that I wanted to write and countries to see and women to love. I hadn’t read Balzac or Henry James. I had never been to the Pitti Palace. I wanted to see my daughters walk autonomously in the world. This is the only life I will ever lead (I murmured on morose midnights at the bar of the Lion’s Head), and to end it in my thirties would be unfair.

Today, I accept the inevitable more serenely. I know that I will never write as many books as Georges Simenon or read as many as Edmund Wilson. Nor will I enter a game in late September to triple up the alley in center field and win a pennant for the Mets. But my daughters live on their own in the world. I have read much of Henry James and the best of Balzac and have walked the marbled acres of the Pitti Palace. Middle age is part of the process of completion of a life, and that is why I’ve come to lose the fear of death. I’ve now lived long enough to understand that dying is as natural a part of living as the falling of a leaf.

And yet, sometimes I wake up in the mornings (usually in an unfamiliar room in a strange city) and in the moments between sleep and true consciousness, I am once again in the apartment on Calle Bahia de Morlaco in Mexico City when I was twenty-one, full of possibilities, with my whole life spread out before me. When I realize where I truly am, and that I am fifty-two and no longer that confused and romantic boy, I am filled with an anguished sadness.

In the three decades since I left Mexico (I was a student of painting there on the GI Bill), I have committed my share of stupidities. The first time around, I was a dreadful husband. I tried to be a good father but made many mistakes. As a young newspaper columnist, drunk with language, I occasionally succumbed to mindless self-righteousness, coming down viciously on public men when I could not bear such an assault myself. I treated some women badly and failed others. There were other sins, mortal and venial.

But in middle age, you learn to forgive yourself. Faced with the enormous crimes of the world (and particularly the horrors of this appalling century), you acquire a sense of proportion about your own relative misdemeanors. You have slowly recognized the cyclical nature of society’s enthusiasms, from compassion to indifference, from generosity to meanness, liberalism to conservatism and back, as the pendulum cuts its inexorable arc in the air. And you know that such cycles are true of individuals too. Each of us goes from the problems of others to the problems of the self and back again, over and over, for the duration of our lives. And most often, we measure our own triumphs and disasters, errors and illusions, against the experiences of others. In middle age, I know that it is already too late to agonize over my personal failings. As Popeye once said, “I yam what I yam an’ that’s all I yam.” The damage of the past is done; nothing can be done to avoid it or to repair it; I hope to cause no more, and I’m sometimes comforted by remembering that to many people I was also kind. For good or ill, I remain human. That is to say, imperfect.

And yet I would be a liar if I suggested that I have no regrets. It is that emotion (not guilt or remorse) that comes to me in half-sleep. I wish I hadn’t wasted so much of my young manhood drinking; I had some great good times, but I passed too much time impaired. A few of those years are completely lost from memory, and memory is a man’s only durable inheritance (I retired from drinking in 1972, with the title). I’ve employed too much of my talent at potboiling, executing other men’s visions for the movies or television, in order to feed and clothe and house my children and to ward off a slum kid’s fear of poverty; at twenty-one, growing up in the ’50s when the worst of all sins was “selling out,” I could not foresee any of that. Through sloth or absorption in work, I allowed some good friendships to wither. I too rashly sold a house I loved and years later still walk its halls and open all of its closets.

I also regret the loss of the illusions of my youth. This is so familiar a process, of course, that it is a cliché. Better men than I, from the anonymous author of the Book of Ecclesiastes to André Malraux, have acquired the same sorrowful knowledge. It’s difficult to explain to the young the heady excitement that attended the election of John F. Kennedy or the aching hole his death blew through this country. More impossible still to tell them that there actually was a time, when I was young, when Americans thought that change could be effected through politics. When Fidel Castro triumphed over Fulgencio Batista on New Year’s Day in 1959,1 cheered with all my friends; now poor Fidel is just another aging Stalinist. Once I embraced the hope for a democratic socialism. There was so much injustice in the world, from Harlem to Southeast Asia, that I wanted to believe in the generous theory of the creed. As Robert Louis Stevenson wrote in one of his essays, “When the torrent sweeps the man against a boulder, you must expect him to scream, and you need not be surprised if the scream is sometimes a theory.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.