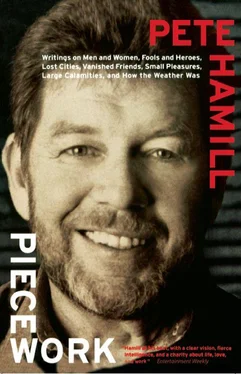

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There were other nouns, of course, common and proper, all now abandoned and rusting like old weapons. Does anyone remember the face of Ngo Dinh Diem, plucked from a Maryknoll retreat in New Jersey in 1954 to become president of the South Vietnam he had not seen in years? Diem was a Catholic in a Buddhist country, a conservative mandarin in a region seething with revolution. Yet the Americans thought he would do just fine. After all, he had been promoted and recommended by Cardinal Spellman, hustled from office to office in Washington to meet the few men in America who knew anything at all about Vietnam. For a while he served Washington’s interests well, refusing to honor the Geneva agreements by taking part in the 1956 elections, which would have unified Vietnam. The reason was simple: in a free election, Ho Chi Minh would have won. And in an American election year, neither John Foster Dulles nor Dwight Eisenhower was prepared to let a Communist come to power in a free election. So Diem built his army, expanded his corps of American advisers, took his American millions. The Communists went back to the hills.

But Diem was remote and mystical. The regime was soon controlled by Diem’s sinister brother, Nhu, a corrupt drug addict, and Diem’s snarling sister-in-law, Madame Nhu. Non-Communist opponents were killed or jailed; puritanical laws were clamped on the population; the South Vietnamese Army — the ARVN — was wormy with thievery and paranoia. And in the early sixties the Vietcong began to fight, and to win. By the time Diem and Nhu were assassinated in a coup on November 1, 1963, and Madame Nhu had departed for exile, the war was almost lost. The Americans came piling in like the cavalry riding to the rescue. Right into the quagmire.

Diem and Nhu and the Dragon Lady are forgotten now, their faces blurred by time. Forgotten too is all the optimistic gush that rolled out of the typewriters of Saigon flacks, the nonsense about strategic hamlets, electronic fences, Special Forces A-Teams, the C.I.D.G., the winning of hearts and minds — all those lights at the end of all those tunnels. A billion words must have issued from the collective mouths of official spokesmen; the men in the black pajamas, however, kept coming down those trails to fight. Who now remembers the hundreds of thousands of words that dropped from the lips of Sir Robert Thompson, who periodically retailed his wisdom to the gullible Americans? He had had a part in the British victory over the Malayan insurgents; that made him an expert. So the Americans listened, while Thompson declared himself a clear-and-hold man rather than a search-and-destroy man, and none of it mattered, because neither strategy worked. In offices in Washington and Saigon, the slick charts looked persuasive; on the field of battle, the Communists were absorbing the most horrendous punishment, and winning.

Only a handful of Americans can remember when M.A.A.G. changed its name to M.A.C.V., or when Chase Manhattan opened its Saigon office, or how many tons of Coca-Cola were unloaded at Cam Ranh Bay. Such details exist in the dusty files of the outfits that managed the war, but they don’t, of course, matter anymore. Other details should. How many remember that the first American killed in Vietnam was Specialist Fourth Class James T. Davis, of Livingston, Tennessee? He died in an ambush on December 22, 1961, just outside Due Hoa, twelve miles from Saigon. The last to die were Marine Corporals Charles McMahon, Jr., twenty-two, of Woburn, Massachusetts, and Darwin Judge, nineteen, of Marshalltown, Iowa. They perished under a North Vietnamese artillery barrage that was laid upon Tan Son Nhut airport on April 29, 1975, the day before the war ended. Their bodies, forgotten in the panic of evacuation, were not brought home until the following March. Their families remember, but almost nobody else in America knows their names. They are as forgotten as the almost 2.5 million Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians who died between 1961 and 1975.

Everybody who went to Vietnam carries his or her own version of the war. Only 10 percent engaged in combat; the American elephant, pursuing the Vietnamese grasshopper, was extraordinarily heavy with logistical support. Tours were for a single year, so a man who \ fought through the 1968 Tet offensive would remember one war, a man who was there in 1971 another. Some cooked eggs in mess halls; others waded through muck in the swamps.

All the reporters remember the Five O’Clock Follies, held downtown in the old Rex Theater under the auspices of JUSPAO (Joint United States Public Affairs Office). These daily briefings, held by the men who clerked the war, were usually a bizarre amalgam of kill ratios, body counts, incident counts, weapons recovered. The flacks were neat, clean, invariably crew-cut, and optimism was the order of the day. Occasionally a visiting politician or labor leader would be introduced, after seventy-two hours in the country, to serve up the official line. The message was understood: surely the richest country on earth, the world’s most powerful military machine, would eventually triumph over these badly equipped, badly fed little Orientals. We had technology. We had B-52S and patrol boats and electronic sensors and fighter planes and aircraft carriers and money, endless billions of dollars. Of course we would win. Above all, we would win because we were right. We would roll back the Communist tide.

Out in the field, the grunts who were fighting one of the best-motivated armies in history knew better. The grunts always knew better.

In Saigon, you didn’t see the infantry of either side. The great early cliché of the war was the irony of sitting in the bar on the roof of the Caravelle Hotel, sipping a vodka and tonic, watching artillery light up the night sky only a dozen miles away. Saigon calls up other memories as well, among those who paid rent there long ago: the zigzagging geometries of traffic, the pedicabs, motorbikes, bicycles, and battered cars coughing up filthy blue exhaust fumes; the damp smell of much handled piasters; the bars of Tu Do Street, not much different from those frequented by the French when the street was the rue Catinat (so carefully described by Graham Greene in The Quiet American, that chillingly prophetic novel, which was ignored by the men who made policy). The whores and bar girls were everywhere, citizens of the country of money; you numbah one, he num-bah ten, you like Saigon tea? The old whorehouses of the French epoch were almost all gone by the time the Americans arrived, banished by the puritanical Diem; the old-timers talked with fondness of mirrored walls and ceilings, silky thighs, elegant meals, opium in ivory pipes, mauve dawns.

That was not the American epoch. There were men who loved women in that country, and many who learned to love the country itself, but you. could never love Tu Do Street, the lithe whispering whores in Mimi’s Bar, the women with the enameled faces whose eyes said nothing. They too were casualties of the war, stunned out of feeling, and their sisters could be found all over the country, wherever young Americans were stationed in large numbers. They lived in the half-dark of the bars, where the music of Aretha Franklin and the Doors and the Stones pounded from the jukeboxes, where phrases were dropped, money was exchanged, and men were led upstairs, or into ambushes. The young Vietnamese men, eyes glittery with hatred, watched the Americans parade their purchased ladies along the avenues, where tamarind trees were dying from the exhaust fumes, and sometimes they reached out and slashed an American belly before vanishing into the crowds. Packs of small children roamed too, forcing collisions, slicing at pockets for wallets, flipping watches off the wrists of drunks. In Saigon, the Americans were far from the war, but living in its very heart.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.