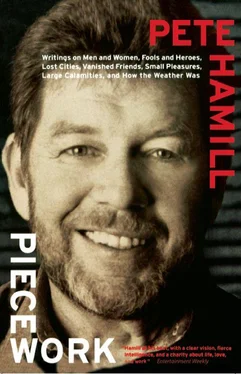

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The novel was, of course, Under the Volcano. Lowry began writing it in December 1936, when he was twenty-seven, and finished the final draft on Christmas Eve 1944. He finished almost nothing else in his life, certainly no other major novel, as he lurched through the United States, Mexico, Tahiti, Italy, and the emptiness of British Columbia, forever a long way from home. He was by his own account an alcoholic, often falling into delirium tremens, sometimes collapsing into Mexican jails or charity wards; he was a terrible husband to both of his wives; he was by most accounts the sort of drunk who would pass a certain point and become a disgusting bore. But about one thing he was certain, and so are we: With Under the Volcano, he made a masterpiece.

When the book at last was published in 1947, critical praise was virtually unanimous (one notable exception was Jacques Barzun, who felt Lowry’s novel was “derivative and pretentious”). The critics marveled at its classical structure, its dense, layered texture, its feeling for history, its use of myth and symbols, and its powerful examination of an alcoholic’s descent into damnation. Lowry’s language was baroque, intense, difficult — a style in direct contrast to the many neo-Hemingways who flourished at the time.

But there was more to the novel’s reception than Lowry’s literary accomplishment. There was also the legend of Lowry, the man. In many ways, he was a throwback to the romantic tradition of the artist consumed by his art to the point of self-destruction. Tales of his drunken escapades were common knowledge in literary circles; such a man was no isolated inhabitant in an academic ivory tower; he was down there carousing with the bandits and groveling with the cockroaches on the floor of the cantina, passing through paradise on the way to the inferno. The novel was not a huge popular success, selling only thirty thousand copies in its first ten years of existence, but that, of course, helped feed the legend; nothing enhances the romantic agony better than neglect. And later the legend was made complete by the squalid facts of Lowry’s death.

Eight years after Volcano’s publication, Lowry and his wife, Margerie, were finally home in England, living in a cottage in Sussex. But home didn’t provide peace; in 1955 and 1956, Lowry was committed to two different London hospitals for psychiatric treatment, in an attempt to combat his alcoholism. By this time, Lowry had failed three times to kill himself, twice to kill his wife. At one point, a lobotomy was even considered. The psychiatrists and the hospitals eventually gave up. After these failures, Lowry returned to the cottage in Sussex, where he wrote sporadically. On June 26, 1957, he had one final row with Margerie and threatened to kill her. She ran to a neighbor’s house for refuge and spent the night. Lowry was found the next morning in his bedroom, a plate of dinner scattered on the floor, along with an almost empty gin bottle and a broken bottle of orange squash. He’d swallowed more than twenty tablets of sodium amytal. It was a dingy way to die. He was forty-seven and was buried in the appropriately named town of Ripe.

The scene is Mexico, the meeting place, according to some, of mankind itself, pyre of Bierce and springboard of Hart Crane, the age-old arena of racial and political conflicts of every nature, and where a colorful native people of genius have a religion that we can roughly describe as one of death, so that it is a good place, at least as good as Lancashire, or Yorkshire, to set our drama of a man’s struggle between the powers of darkness and light. Its geographical remoteness from us, as well as the closeness of its problems to our own, will assist the tragedy each in its own way. We can see it as the world itself, or the Garden of Eden, or both at once. Or we can see it as a kind of timeless symbol of the world on which we can place the Garden of Eden, the Tower of Babel, and indeed anything else we please. It is paradisal: It is unquestionably infernal. It is, in fact, Mexico.

— Malcolm Lowry to Jonathan Cape

January 2, 1946

Almost from the beginning, there was talk of a movie. This was itself surprising. The best movies generally come from pulp material, where action, narrative, character exist on the surface of the work; literary masterpieces, with their refinements of prose style and their deep interior lives, tend to resist adaptation to film. But Under the Volcano had two major attractions.

One was its principal character: the Consul. His name was Geoffrey Firmin, the despairing, alcoholic British envoy in the Mexican city of Quahnahuac (Lowry’s name for Cuernavaca). Eleven of the novel’s twelve chapters take place on the Day of the Dead, 1938, when the Consul goes on one final drunken odyssey that ends, as all tragedies do, in death. There are other characters: the film director Jacques Laruelle; Yvonne, the Consul’s estranged wife and a former film actress, who has returned to Mexico in one final attempt to rescue the Consul from damnation; Hugh, the Consul’s half brother, who shares his belief in the values of Western civilization, but actually does something about them, going off to the Spanish Civil War. Yvonne has betrayed the Consul by sleeping with Laruelle and Hugh, and is a critical character in the drama. But the novel belongs to the Consúl, and his intense, brooding, ironic, sometimes comic, and ultimately tragic self-absorption. He is a character, like Lear, that actors would kill for the chance to portray.

The second protagonist is Mexico itself. Lowry’s volcanoes rise to heaven; the barranca lies behind the villas and cantinas, winding through Quahnahuac, choked with the rotting garbage of history. On the Day of the Dead, the Consul is faced with a fearful choice: escape to heaven or descent into hell, and he lives his last hours in a private purgatory. Mexico is a perfect setting for such a drama. And almost no foreigners have evoked that country with such chilling accuracy as Lowry. He and the Consul traverse the cruel landscape together, and then abruptly face the abyss.

All of this is told in a way that has always attracted movie people. In fact, Lowry himself longed to write the screen version of his own novel. Frank Taylor, a friend who went to work for MGM in 1949, told Lowry he was working on a film of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night. Lowry, perhaps thinking a successful production of Fitzgerald’s novel would lead to an MGM commission for Under the Volcano, bestowed on Taylor an unsolicited script of Tender Is the Night. It was about five hundred pages long, and Taylor described it in 1964 as “a total filmic evocation — complete with critical remarks, attached film theory, directions to actors, fashions, automobiles: The only things like it are the James Agee scripts.” Neither project happened.

In 1962, the actor Zachary Scott optioned Under the Volcano, but couldn’t get it made, and after his death in 1965, his widow sold the rights to the Hakim brothers (Robert, Raymond, and Andre), who wanted Luis Buñuel to direct. This began a long, tangled story of hirings and firings, scripts and revisions and announcements of productions that never materialized. Buñuel gave way to Jules Dassin, who, in turn, was replaced by Joseph Losey. The Hakims’ option lapsed; they sued the Lowry estate and lost. Then one Luis Barranco acquired the rights. More scripts. Even Gabriel Garcia Marquez took a crack at a treatment, as did Carlos Fuentes; directors Ken Russell and Jerzy Skolimowski were involved at other points. When the professionals failed, amateurs tried: Students read the novel and wrote adaptations: cultists, kabalists, professors, actors, all tried to transform their totemic novel into a workable movie script. And many of these versions arrived eventually in the hands of director John Huston.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.