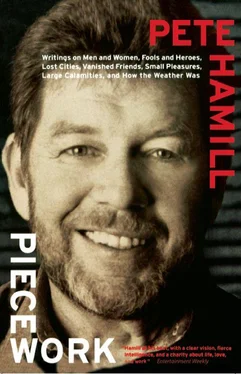

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And then directly in front of us, oblivious to everything, looking straight ahead as he walks west against the red light, is an older man. Until this moment, he has been screened by those who have hurried to the corner, and now he is suddenly, vulnerably, alone. The driver blares the horn, hits the brakes, tries to move left, finds that lane blocked by another car, and then there is a hard socking thump, metal smashing into bone, and a blurred image of the man as we go by, the man rolling, brakes screeching, my daughter’s scream, and we are stopped.

I look at the older man, who is on his back. Blood pumps from his mouth. He is shoeless. His body doesn’t move. And then the crowd, frozen in horror, comes alive. The driver is breathing shallowly, his head on the wheel, holding the wheel with both hands, gripping it. “No,” he says. “No. No.” He taps his head on the wheel. “Shit.” He gazes to his left, away from the fallen man, and then slowly turns, sees the smear of blood. “No,” he says. “No.”

My daughter is sobbing now, and I try to comfort her, and I hear people shouting, “Don’t move him” and “Call the police, you asshole, call the police.” And then part of the crowd turns ugly. A suety young man in a zipper jacket comes to the door on the driver’s side. “You doin’ sebenty miles an hour, man! You murder the guy!” Another shouts: “Fuckin’ cab driver, runnin’ the yellow light, yeah, that muthafucka!”

I get out of the cab. There are no police on the scene yet and all of this has happened in a couple of minutes. I try to calm down the angrier people, explaining I was in the cab, that the driver wasn’t speeding, that the old man simply had not responded, that he was clearly walking across the red light. “Still, he should go slow! Look, that’s an old man!”

That’s the way most of us are in New York these days; we have been trained by television and politics to retaliate. An old man is knocked to the ground by a cab, his life spilling onto the dirty tar, and people want to hurt someone back. The driver starts out of the cab. The suety man screams at him. The cab driver explains with some heat about his speed, about his horn, about the red light, but the suety man’s eyes are blazing and others are behind him. The passions of a mob are stirring in the cold damp air. “Mothafucka, you drive like a crazy man …”

I tell the driver to get back in the cab and keep quiet. Then behind us, pushing through the clotted traffic, comes a police car. The crowd abruptly ends its transformation into a mob. More sirens in the distance. The sense of time slowed is replaced by time become swift. Cops and medics work expertly on the stricken man; his body is covered with rubber sheets for warmth; they press down on his chest. Younger cops move the crowd onto the sidewalk, others try to get the traffic moving. An older cop with a sad, grave face picks up the man’s brown loafers.

“I’m through,” the driver says. “I can never drive a cab again. I can’t even drive this one today.” He says he was born in Spain and his family moved to the Dominican Republic when he was six; he has lived in New York since his teens. That night, after months of waiting, he was to see La Cage aux folles. “How can I see something like that after this?”

This is how a life can end: The cops take statements. An ambulance arrives from St. Vincent’s and the bloody-faced man is placed on a stretcher and into the back; it moves off with siren screaming, slowing behind jammed traffic at 23rd Street. From the lofts of the furriers above the avenue, people gaze down at the scene. Beside the tractor-trailer, there is a two-foot strand of blood, bright red against the dirty tar, and some plastic tubes that had been slipped down the stricken man’s throat. His gray plaid hat has rolled under the truck and lies beside the curb. I see a policeman’s hand reach down, circle it with chalk, pick it up. A pause. Then he drops it back in place.

“I know this man,” a white-haired man whispers. “I saw him 20 minutes ago.” I ask him for his name and the name of the man who has been carried away. He is reluctant to give either, and drifts away. The police are also careful; they first want to notify next of kin. The cab driver (still waiting for formal questions) hears this: “Is he — is the man dead?” The cop shrugs sadly. The driver leans on his cab, his body wracked with dry heaves.

This is how a life can end: All the questions have been asked, the forms filled in, names given, witnesses questioned. About an hour has passed. Traffic now moves quickly down the avenue. There is tape where the taxi’s wheels had come to a halt, darkening blood and chalk marks and a hat where the old man had come to the end of his life. A woman moves between two parked cars, waits for a break in traffic, hurries across the street. She never sees the blood. A gust of wind lifts the dead man’s sporty little hat and rolls it back against the curb.

VILLAGE VOICE,

March 18, 1986

BRIDGE OF DREAMS

In all years and all seasons, the bridge was there. We could see it from the roof of the tenement where we lived, the stone towers rising below us from the foreshortened streets of downtown Brooklyn. We saw it in newspapers and at the movies and on the covers of books, part of the signature of the place where we lived. Sometimes, on summer afternoons during World War II, my mother would gather me and my brother Tom and my sister, Kathleen, and we’d set out on the most glorious of walks. We walked for miles, leaving behind the green of Prospect Park, passing factories and warehouses and strange neighborhoods, crossing a hundred streets and a dozen avenues, seeing the streets turn green again as we entered Brooklyn Heights, pushing on, beaded with sweat, legs rubbery, until, amazingly, looming abruptly in front of us, stone and steel and indifferent, was The Bridge.

It was the first man-made thing that I knew was beautiful. We could walk across it, gazing up at the great arc of the cables. We could hear the sustained eerie musical note they made when combed by the wind (augmented since by the hum of automobile tires), and we envied the gulls that played at the top of those arches. The arches were Gothic, and provided a sense of awe that was quite religious. And awe infused the view of the great harbor, a view my mother embellished by describing to us the ships that had brought her and so many other immigrants to America — the Irish and the Italians and the Jews, the Germans, the Poles, and the Swedes, all of them crowding the decks, straining to see their newfound land. What they saw first was the Statue of Liberty, and the skyline, and The Bridge. The Brooklyn Bridge.

My mother would tell us these things and then lead us down to the Manhattan side and show us Park Row, where the newspapers were, and City Hall, where a wonderful man named Fiorello worked as mayor, and the Woolworth Building, gleaming in the sun. Near dusk we’d take the trolley car back across to Brooklyn. I remember on one of those trips wanting to jump out and climb The Bridge’s cables and wrap my arms around those stone towers; nothing that immense could be real. The impulse quickly vanished. I had already walked the promenade and touched the stone and run my hands along the steel; I was from Brooklyn, and to me The Bridge was not a ghost, a painting, a photograph, or a dream. It was a fact. In the years that followed, everything changed, including me, but The Bridge was always there.

It has been there now for a hundred summers. Fiorello is gone, and so are the newspapers of Park Row. The last trolley crossed The Bridge in 1950. The Bridge has been altered, cluttered with the ugly advancements of the twentieth century. But it is as beautiful to me today as it was when I was young and had more innocent eyes. I was a teenager before I realized that all those puny, misshapen other bridges across the river even had names.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.