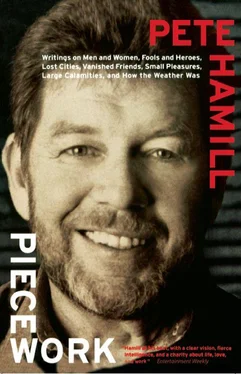

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In this city, racism is not an abstraction to be discussed in a sociology class; usually the virus comes from concrete experience. Many blacks can cite a catalogue of insults and injuries, from the refusal of a cab driver to stop on a rainy night to the white policeman using his baton as if he were judge, jury, and executioner. But this is also true of those who are victimized by blacks. The other day I saw four well-dressed black teenagers coming along Broadway. It was midafternoon. School was just out. They went past a Korean fruit and vegetable store, and then, all at once, darted back. Each stole something: an orange, a cantaloupe, an apple, some grapes. They began to run, and a Korean man in his forties ran after them in vain. But when he came back he was still seething with fury.

“I work, I work!” he shouted in a thin, high, frustrated voice. “I work all day, all night. And they steal They just steal. They don’t work. It’s not fair!” The man said he just didn’t understand. This happens three, four times a week; never the same young men; always blacks. Would four Koreans come down the street and steal from a black grocer? “Why don’t they work?” After six years in this country, and two years in business, “they” had become a loaded word in his vocabulary. And probably a permanent one.

Driving through central Brooklyn one afternoon, through mile after mile of men clustered together on street corners while women without men were engulfed by children, driving through blasted streets smelling of defeat and abandonment, I remembered a scene I had witnessed many times last year in the cities of the American South: black families dining together in restaurants. Children. A mother. A father. I’ve been back in New York now for five weeks and haven’t seen such an event yet. Thirty years after the freedom rides, the North might now have much to learn from the South.

Squalor is, of course, only part of the city. This remains a city of enormous energy, great museums and theaters, generosity and wit, splendid architecture. But in my half-century here, I’ve never seen social disparity as violently drastic as it is now. In the evenings in Manhattan, you often pass among people who look like drawings by George Grosz. Suddenly and ferociously rich, the men eat their way through the city, consuming food, wine, art, real estate, companies, stores, neighborhoods. They are all appetite and no mind, no heart. During the day the women prowl Madison Avenue or 57th Street as if searching for prey, buying clothes, buying breasts, buying paintings, buying status. In a city where human beings struggle for the privilege of sleeping over subway grates, these people even have money to hire “art advisers”; this is like hiring a fuck adviser.

One day, soon after I was back, I wandered around Wall Street to look at the inhabitants. Every other person seemed high, either on cocaine or the platinum roar of the stock market. In one of the restaurants, I struck up a conversation with a broker. I asked him if any of the immense transactions in the bull market would produce either goods or jobs. “No, just money,” he said and laughed. But when I asked him if the sight of the homeless disturbed him, the grin turned to a sneer: “Hey, man, there’s nothing I can do about that. That’s an old movie. That’s the ’60s, pal.”

Well, no, not the ’60s. The ’80s. But for all of that it was good to be home.

VILLAGE VOICE,

May 5, 1987

GOD IS IN THE DETAILS

The wonder is that there is any beauty left at all. The century’s assault has been relentless. Every year, another fragment of grace or style or craft is obliterated from New York, to be replaced by the brutally functional or the commercially coarse. Vandalism is general. I don’t mean only those morons with spray cans, whose brainless signatures now mar even the loveliest old carved stone. There are corporate vandals, too, political vandals, and vandals equipped with elaborate aesthetic theories. They never rest, and when they strike, their energy is ferocious.

And yet, beauty persists — scattered across the city, the beauty of nature, and of things made by men and women. There is beauty above as people hurry through the city streets. It nestles behind the fortress walls of banal structures, and sometimes stands unrevealed before our eyes. In recent years, the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the Municipal Art Society, and other groups have done splendid work preserving what remains of the past, but much is already lost, and everywhere there are valuable and beautiful creations under threat. Still, there are places whose value need not be ratified by a committee; they are hidden islands of the marvelous, capable of evoking emotional, even mysterious, responses.

I don’t know the name of the sculptor whose flowers, cupids, and ornamental letters adorn the façade of the Stuyvesant Polyclinic, on Second Avenue between St. Marks Place and 9th Street, but I love his excess, the showering extravagance of his talent. The man who wrought the iron steps and balconies of the townhouse at 328 East 18th Street is unknown to me, but although he did his job in 1852, his work is here today to pleasure the eye. The Montauk Club, in Brooklyn, has always been part of my life; as a child, I’d gaze up at the frieze of Indians around the top of the building and invent tales to go with those faces and figures; today, I marvel at the audacity of the men who made the building, shamelessly lifting the basic design from a Venetian palace and then localizing it with a narrative of the first Americans.

All such places have a personal meaning. Why do the sprawling Victorian houses in Clinton Hill seem so melancholy now? Powerful men once lived in this Brooklyn neighborhood, in the area around Pratt Institute, raising huge families far from the congestion of Manhattan; in summer now I expect to see Mark Twain emerge onto a porch in a white suit to hector the millionaires who are his hosts, or I envision Jack Johnson walking defiantly on these streets with his white wife. The Billopp House, on Staten Island, can summon a more remote era; built in 1680 by the British military man who won Staten Island from New Jersey in a boat race, this austere and serene building stands at one end of Hylan Boulevard like a reproof. In front of such a house, or on Grace Court, in Brooklyn, or along some of the elegant streets of Bedford-Stuyvesant, there comes the urge to be still.

Stillness, in fact, is probably the only condition that will allow the city’s beauty to reveal itself. You can’t experience it from the window of a careening taxi, or rushing from subway to office. Time must be taken, imagination engaged. I’m convinced that one of this city’s greatest architects was a Brooklynite named Ernest Flagg, who died in 1947 at age 90. He designed the old Mills hotel, on Bleecker Street (the Village Gate is on the ground floor), St. Luke’s Hospital, and the Flagg Court housing complex, in Bay Ridge. He had a long, productive career, living in a house of his own design at 109 East 40th Street and on an estate on Staten Island.

Today, he is almost completely forgotten — except for two masterpieces. One is the “little” Singer building, at 561 Broadway, near Prince Street, complete with wrought-iron railings, its façade sheathed in orange and blue terra-cotta. The other is the Scribner bookstore, at 597 Fifth Avenue. His greatest masterpiece, however, is gone. This was the Singer tower, at 149 Broadway, a Beaux-Arts extravaganza full of decoration and briefly the tallest building in the world when it went up in 1908. I used to visit there when I worked downtown at the old New York Post; the building was a romantic affront to all the reigning dogmas of the Bauhaus. I loved it. Then it fell into the hands of United States Steel and was, of course, demolished.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.