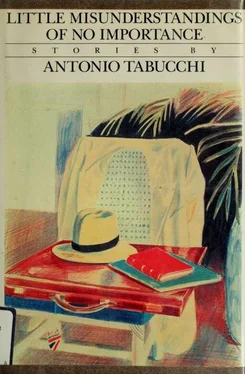

Antonio Tabucchi - Little misunderstandings of no importance - stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Antonio Tabucchi - Little misunderstandings of no importance - stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1987, Издательство: A New Direction Book, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:A New Direction Book

- Жанр:

- Год:1987

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Translation of: Piccoli equivoci senza importanza

Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I wanted to stay on the sidelines. Albert called the Countess at the Hotel de Paris to find out if she knew what had become of the elephant. It had simply disappeared; in any case, it was lost, he reported. The car had been standing too long; she says to make a copy. And so we had three weeks to do something about it, while we were touching up the engine and the upholstery. One cylinder needed adjusting, but that was not a big job. The upholsterer was a wily young fellow with a shop on the Rue Le Peletier, who sent antique fabrics to be repaired by the nuns of a certain convent. There’s nobody like a nun for a painstaking job, believe me, and their mending was invisible; it was all done on the reverse side, where it left a network of threads like a telephone exchange. The worst thing was the elephant. A sculptor of sorts offered to make a clay copy to be covered with metal, but bumps and jolts would soon have caused it to crack. Finally Albert thought of a cabinetmaker from Lorraine — this story is full of Lorrainers — who had a shop in the Marais, an old fellow who carved wood in naturalistic style. It was easy enough to find a photograph of the elephant, which we took to the old man, together with the exact measurements, telling him to make an identical copy. After that we had to see to the chrome plating, and that came out satisfactorily. Of course, if you looked at the figure when the car was standing still you could see that it was a fake, but in motion it seemed like the real thing.

The morning of our departure was quite an event. Albert had fallen completely into the role of father, and kept asking whether I needed this or had forgotten that. The day before I’d bought a leather suitcase — the car and the trip deserved nothing less — as well as a cream-colored linen jacket and another in leather and an Italian silk scarf. When I got to the Hotel de Paris a liveried doorman opened the car, and, feeling like the Marquis of Carabas, I told him to call the Countess. A porter came with a valise and a vanity case; she arrived, on her husband’s arm, greeted me distractedly and got into the back seat. Here was the first surprise of the day. I had been fearful of seeing the Count again because I didn’t exactly like him, but he spoke to me as if we’d never met, playing the part to perfection. It was a Monday towards the end of June. “We’ll meet in Biarritz a week from today,” he said affably to his wife. “If you like you can send your driver to pick me up at the station — my train gets in at eight thirty-five in the evening; otherwise we’ll meet at the Hotel des Palais.” I went into first gear, and she gave a brief wave of her hand through the open window.

The second surprise was her telling me to take the Route Nationale 6, and her tone of voice, a dry, decisive tone which seemed to reflect a strong will or else some sort of phobia. I objected that this wasn’t the shortest way to Biarritz. “I want to take another route,” she said sharply, “I’d appreciate it if you didn’t argue the point.” And there was a third surprise as well. When I first met her at Chez Albert she was so defenceless and such an open book that I thought I could read her whole life on her face; now, instead, she had withdrawn behind a mask of distance and reserve, like a real countess. She was beautiful, and that was no surprise, but now she seemed to me of an absolute beauty, because I understood that no beauty in the world is greater than that of a woman, and this, you’ll understand, Monsieur, put me into a sort of frenzy. Meanwhile the Bugatti glided over the gentle, inviting roads of France, up and down and along level stretches, the way our roads go, bordered by plane trees on either side. Behind me the road retreated, before me it opened up, and I thought of my life and the boredom of it, and of what Albert had said to me, and I felt ashamed that I’d never known love. I don’t mean physical love, of course, I’d had that, but real love, the kind that blazes up inside and breaks out and spins like a motor while the wheels speed over the ground. It was like that, a sort of remorse, an awareness of mediocrity or cowardice. Up to now my wheels had turned slowly and tediously over a long, long road, and I couldn’t remember a single landscape along the way. Now I was travelling another road, which led nowhere, with a beautiful and distant woman who was escaping or fleeing from I knew not what. It was a useless race across France, I felt quite sure, on a road as empty as those that had gone before. Those were my exact thoughts at that particular moment. Limoges was not far, we were deep in the countryside, where farmers were working among their fruit trees. Limoges, I thought, what does Limoges have to do with my life? I drew the car over to the side of the road and stopped. Turning towards her, I said: “Look here…” Before I could say any more she laid a finger gently across my lips and murmured: “Don’t be a fool, Carabas.” Without another word she got out and came to sit beside me. “Go on,” she said, “I know that we’re taking an absurd route, but perhaps everything’s absurd, and I have my reasons.”

It’s a curious sensation to arrive in a strange city, knowing that there you’ll love with a love you’ve never experienced before. That’s how it was. We stopped at a little hotel on the river — I don’t remember the name of the river that runs by Limoges. The room had faded wallpaper and very ordinary furniture; in those years many hotels were like that; you’ve only to look at the films of Jean Gabin. Miriam asked me to say that she was my wife, she didn’t want to identify herself and the hotel didn’t ask for the papers of both members of a couple. From the room we could see the river, bordered by willows; it was a fine night and we fell asleep at dawn. “Who is it you’re running away from, Miriam,” I asked her. “What’s wrong in your life?” But she laid a finger across my lips.

An absurd route, as I said before. We went down to Rodez and then towards Albi and its vineyards, because of a landscape she wanted to see. I thought it was an outdoor view but it was a painting, and we found it. We skipped Toulouse and made for Pau, because her mother had spent her childhood there, and I lingered over the idea of her mother as a child, in a boarding school which we couldn’t locate. It was the first time I’d thought of the childhood of a woman companion’s mother, a new and strange sensation. We looked at the splendid square and at the houses, with their white attic windows suspended from tile roofs, and I imagined a winter in Pau, behind one of those windows. I was tempted to say: Listen, Miriam, let’s forget about everything else and spend the winter behind one of these windows, in this city where nobody knows us.

When we got to Biarritz it was Saturday; the rally was to be the next day. I thought we’d go to the Hotel des Palais and take two rooms there, but she chose to go elsewhere, to the Hotel d’Angleterre, and she signed the register in my name. In luxury hotels, too, they don’t ask to see a woman’s papers. She was hiding out, obviously, and I was haunted by the strange sentence she had pronounced on the day of our first meeting, a subject to which she refused to return. I put my hands on her shoulders and looked into her eyes — we had gone down to the beach at sunset, seagulls were standing around, a sign of bad weather, they say, and some children were playing in the sand. “I want to know,” I told her, and she said: “Tomorrow you’ll know everything. Tomorrow evening, after the rally, we’ll meet here on the beach and go for a drive in the car. Don’t insist, please.”

The rally rules demanded that every driver be dressed in the style of the period of his car. I had bought a pair of baggy Zouave-style trousers and a tan cloth cap with a visor. “This is a show,” I said to Miriam; “it’s not a race, it’s a fashion parade.” But she said no, I’d see. Competition wasn’t the order of the day, but almost. The course ran along the ocean, a road riddled with curves hanging over the water: Bidart, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Donibane and, finally, San Sebastian. We set out three by three, our names drawn by lot, regardless of the type of car. The time was to be clocked and calculated according to each car’s horsepower. And so we started out with a 1928 Hispano-Suiza, called La Boulogne, and a bright red 1922 Lambda, a superb creation (suffice it to say that Mussolini had one). Not that the Hispano-Suiza was to be sneezed at; it was definitely elegant, with its bottle-green coupe body and long chrome hood. We were among the first to take off, at ten o’clock in the morning. It was a fine typically Atlantic day, with a cool breeze and clouds flitting across the sun. The Hispano-Suiza took off like a shot. “We’ll let it go,” I said to Miriam; “I refuse to let others set the pace; we’ll catch up when I feel like it.” The Lambda stayed quietly behind. It was driven by a fellow with a black moustache, accompanied by a young girl, probably rich Italians, who smiled at us and every now and then called out ciao. They remained behind us on all the curves until Saint-Jean-de-Luz, then they passed us at Hendaye, the border town, and began to slow up on the straight, flat road to Donibane. I thought it was strange that they should linger at this particular point. We had passed the Hispano-Suiza before arriving at Irun; now I meant to step on the accelerator and I expected the driver of the Lambda to do likewise. Instead, he let us pass with the greatest of ease. For a hundred yards or so we were side by side; the girl waved and laughed. “They’re out for a good time,” I said to Miriam. They caught up with us at the end of the straight, at which point there were two nasty curves in rapid succession. We’d tried them out the evening before, and they were imprinted on my memory. Miriam cried out when she saw them coming at us, pushing us towards the precipice. Instinctively I braked and then accelerated, managing to hit the Lambda. It was a hard, quick blow, enough to throw the Lambda off the road, to the left, where it slithered along the inside embankment for about twenty yards. I was following the scene in the rear-view mirror as the Lambda lost a fender against a pole, skidded towards the centre of the road and then back to the left where, having run out of all impetus, it bogged down in a pile of dirt. Plainly the passengers were not injured. I was drenched with cold sweat. Miriam clasped my arm. “Don’t stay,” she said, “please, please don’t stay,” and I drove on. San Sebastian was directly below us; no one had witnessed the incident. After passing the finish line I made for the improvised, open-air garage, but I didn’t get out of the car. “It was intentional,” I said; “they did it on purpose.” Miriam was very pale, and speechless, as if petrified. “I’m going to the police to report it,” I said. “Please,” she murmured. “But don’t you see that they did it on purpose?” I shouted. “That they were trying to kill us?” She looked at me, with an expression half troubled, half imploring. “You can take care of the car,” I said; “get the bumper straightened while I walk around.” And I got out, slamming the door; there was nothing seriously wrong with the car and the whole thing could have been just a bad dream. I wandered around San Sebastian, especially along the sea. It’s a fine city, with those white late nineteenth-century buildings. Then I went into an enormous cafe — the sort you find only in Spain, the walls lined with mirrors and a restaurant attached to it — and ate some fried fish.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Little misunderstandings of no importance : stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.