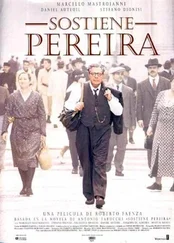

Father António sat down on a bench in the sacristy and Pereira sat beside him. Listen Father António, said Pereira. I believe in Almighty God, I receive the sacraments, I obey the Ten Commandments and try not to sin, and even if I sometimes don’t go to Mass on Sundays it’s not for lack of faith but just laziness, I think of myself as a good Catholic and have the teachings of the Church at heart, but at the moment I’m a little confused and also, although I’m a journalist, I’m not well informed about what’s going on in the world, and just now I’m very perplexed because it seems there’s a lot of argument about the position of the French Catholic writers with regard to the civil war in Spain, I’d like you to put me in the picture Father António, because you know about things and I’d like to know how to behave so as to avoid falling into heresy. But Pereira, exclaimed Father António, you must be living in another world! Pereira tried to justify himself: Well, the fact is I’ve been a week in Parede and what’s more I haven’t bought a foreign paper all summer, and you can’t learn much from the Portuguese papers, so the only news I get is café gossip.

Pereira maintains that Father António got to his feet and towered over him with an expression which seemed to him menacingly stern. Pereira, he said, this is a very grave moment and everyone has to make up his own mind, I am a churchman and have to obey my religious superiors, but you are free to make personal decisions, even though you are a Catholic. Then explain me everything, implored Pereira, because I’d like to make my own decisions but I’m not in the know. Father António blew his nose, crossed his hands on his breast and asked: Have you heard of the problem of the Basque clergy? No, I haven’t, admitted Pereira. Well, said Father António, it all began with the Basque clergy, because after the bombing of Guernica the Basque clergy, who are considered quite the most Christian people in Spain, took sides with the Republic. Father António blew his nose as if deeply stirred and continued: In the spring of last year two famous French Catholic writers, Francois Mauriac and Jacques Maritain, published a manifesto in defence of the Basques. Mauriac! exclaimed Pereira, I said not long ago that we ought to have an obituary ready for Mauriac, he’s worth his salt that man, but Monteiro Rossi didn’t manage to write me one. Who is Monteiro Rossi? asked Father António. He’s the assistant I’ve taken on, replied Pereira, but he can’t seem to write me obituaries for the Catholic writers who have taken up decent political stances. But why do you want an obituary for him, asked Father António, poor Mauriac, let him live, we need him, why d’you want to kill him off? Oh, that’s not what I meant at all, said Pereira, I hope he lives to be a hundred, but suppose he were to die suddenly, then there’d be at least one paper in Portugal ready to give him his due, and that paper would be the Lisboa , but forgive the interruption Father António, please go on. Well, said Father António, the problem was complicated by the Vatican, which claimed that thousands of the Spanish clergy had been killed by the republicans, that the Basque Catholics were ‘Red Christians’ and deserved to be excommunicated, and sure enough it excommunicated them, and to make matters worse Claudel, the famous Paul Claudel, a Catholic writer himself, wrote an ode ‘Aux Martyrs Espagnols’ as the preface in verse to a swinish propaganda leaflet produced by a Spanish nationalist agent in Paris. Claudel! exclaimed Pereira, Paul Claudel? Father António blew his nose yet again. The very same, said he, and how would you define Paul Claudel, Pereira? Well, on the spur of the moment I couldn’t presume to say, replied Pereira, he’s a Catholic but he’s taken a different stance, he has made his decisions. On the spur of the moment you couldn’t presume to say, Pereira! exclaimed Father António in turn, well let me tell you that Claudel is a son of a bitch, that’s what he is, I’m sorry to utter these words in a holy place because what I’d really like to do is shout them from the housetops. What happened next? enquired Pereira. Then, continued Father António, the hierarchy of the Spanish Church, led by Cardinal Gomá, Archbishop of Toledo, decided to send an open letter to all the bishops in the world, you get that Pereira? all the bishops in the world, as if all the bishops in the world were damn great Fascists like them, saying that thousands of Christians in Spain had taken up arms of their own accord in defence of the principles of religion. Yes, said Pereira, but what about these Spanish martyrs, all these murdered clergy? Father António was silent for a moment and then said: Martyrs they may possibly be, but the fact remains they were plotting against the Republic, and don’t forget that the Republic was constitutional, it had been elected by the people, Franco has made a coup d’état, he’s a bandit. And Bernanos, asked Pereira, what’s Bernanos got to do with all this? he’s a Catholic writer too. He’s the only one with first-hand knowledge of Spain, said Father António, from ’Thirty-Four until last year he was in Spain himself, he has written about the massacres by Franco’s troops, the Vatican can’t abide him because they know he’s a genuine witness. You know, Father António, said Pereira, it has occurred to me to publish a chapter or two of the Journal d’un curé de campagne on the culture page of the Lisboa , what do you think? I think it’s a splendid idea, replied Father António, but I don’t know if they’ll let you do it, there’s no love lost for Bernanos in this country, he’s made some pretty harsh comments on the Viriato Battalion, that’s the Portuguese military contingent fighting for Franco in Spain, and now you must excuse me Pereira, I must be off to the hospital, my sick parishioners are expecting me.

Pereira got up to take his leave. Goodbye Father António, said he, I’m sorry to have taken so much of your time, my next visit I’ll make a proper confession. You don’t need to, replied Father António, first make sure you commit some sin and then come to me, don’t make me waste my time for nothing.

Pereira left him and clambered breathlessly up the Rua da Imprensa Nacional. When he reached the church of San Mamede he crossed himself, then dropped onto a bench in the little square, stretched out his legs and settled down to enjoy a breath of fresh air. He would have liked a lemonade, and there was a café only a few steps away. But he resisted the temptation. He simply relaxed in the shade, took off his shoes for a while and let the cool air get to his feet. Then he set off slowly for the office revolving many memories. Pereira maintains he thought back on his childhood, a childhood spent at Póvoa do Varzim with his grandparents, a happy childhood, or at least one that seemed happy to him, but he has no wish to speak about his childhood because he maintains it has nothing to do with these events and that late August day when summer was on the wane and his mind in such a whirl.

On the stairs he met Celeste who greeted him cheerily and said: Good morning Dr Pereira, no post for you this morning or telephone calls either. How d’you mean, telephone calls, exclaimed Pereira, have you been into the office? Of course not, replied the caretaker with an air of triumph, but some workmen from the telephone company came this morning accompanied by an official, they connected your telephone to the porter’s lodge, they said it’s as well to have someone to receive the calls when there’s no one in the office, and they say I’m a trustworthy person. All too trustworthy as far as that lot are concerned, Pereira would dearly like to have retorted, but he said nothing of the kind. All he asked was: And what if I have to make a call myself? You have to go through the switchboard, replied Celeste smugly, from now on I am your switchboard, and you have to ask me to obtain the numbers, and I assure you I’d have preferred not to, Dr Pereira, I work all morning and have to get lunch for four people, because I have four mouths to feed, I do, and apart from the children who get what they get and like it I have a husband who’s very demanding, when he gets back from headquarters at two o’clock he’s as hungry as a hunter and very demanding. I can tell that from the smell of frying always hanging about on the landing, replied Pereira, and left it at that. He went into the office, took the receiver off the hook and reached into his pocket for the sheet of paper Marta had given him the evening before. It was an article written by hand in blue ink, and at the top was printed: ANNIVERSAIES. It read: ‘Eight years ago, in 1930, the great poet Vladimir Mayakovsky died in Moscow. He shot himself after being disappointed in love. He was the son of a forestry inspector. After joining the Bolshevik party at an early age he was three times arrested and was tortured by the Czarist police. A great propagandist for the Russian revolution, he was a member of the Russian Futurist group, who are politically quite distinct from the Italian Futurists. He toured his country on board a locomotive reciting his revolutionary poems in every village along the way. He aroused great enthusiasm among the people. He was an artist, designer, poet and playwright. His work is not translated into Portuguese, but may be obtained in French from the bookshop in Rua do Ouro in Lisbon. He was a friend of the great Eisenstein, with whom he collaborated on a number of films. He left a vast opus of poetry, prose and drama. In him we celebrate a great democrat and a fervent anti-Czarist.’

Читать дальше