“You’re coming back for a visit,” they say. “You’re checking out the skyline and the Arch.”

The cameraman, Chris, is a barrel-chested, red-faced local with a local accent. The producer, Gregg, is a tall, good-looking cosmopolitan with fashion-model locks. Through the window of my rental car, Gregg gives me a walkie-talkie with which to communicate with him and the crew, who will be following me in a minivan.

“You’ll want to drive slow,” Chris says, “in the second lane from the right.”

“How slow?”

“Like thirty-five.”

In the distance I can see commuter traffic, still heavy, on the elevated roadways that feed the Poplar Street Bridge. There’s a hint of illegality in our plotting by the side of a road here, in East St. Louis wastelands suitable for dumping bodies, but we’re doing nothing more dubious morally than making television. Any commuters we might inconvenience won’t know this, of course, but I suspect that if they did know it — if they heard the word “Oprah”—most of them would mind the inconvenience less.

After I’ve tested the walkie-talkie, we drive back to a feeder ramp. I’ve spent the night in St. Louis and have come over the bridge for no other reason than to stage this shot. I’m a Midwesterner who’s been living in the East for twenty-four years. I’m a grumpy Manhattanite who, with what feels like a Midwestern eagerness to cooperate, has agreed to pretend to arrive in the Midwestern city of his childhood and reexamine his roots.

The inbound traffic is heavier than the outbound was. A tailgater flashes his high beams as I brake to allow the camera van to pull even with me on the left. Its side panel door is open, and Chris is hanging out with a camera on his shoulder. In the far right lane, a semi is coming up to pass me.

“We need you to roll down your window,” Gregg says on the walkie-talkie.

I roll down the window, and my hair begins to fly.

“Slow down, slow down,” Chris barks across the blurred pavement.

I ease up on the gas, watching the road empty in front of me. I am slow and the world is fast. The semi has pulled up squarely to my right, obscuring the Gateway Arch and the skyline that I’m supposed to be pretending to check out.

Chris, leaning from the van with his camera, shouts angrily, or desperately, above the automotive roar. “Slow down! Slow down!”

I have a morbid aversion to blocking traffic — inherited, perhaps, from my father, for whom an evening at the theater was a torment if somebody short was sitting behind him — but I obey the shouted order, and the semi on my right roars on ahead of me, unblocking our view of the Arch just as we leave the bridge and sail west.

Over the walkie-talkie, as we reconnoiter for a second take, Gregg explains that Chris was shouting not at me but at his assistant, who is driving the van. Every time I slowed down, they had to slow down further. I feel sheepish about this, but I’m happy that nobody got killed.

For the second take, I stay in the far right lane and poke along at half the legal speed limit, trying to appear — what? writerly? curious? nostalgic? — while the trucker behind me looses blast after blast on his air horn.

In front of St. Louis’s historic Old Courthouse, where the Dred Scott case was tried, Chris and his helper and I wait in suspense while Gregg reviews the new footage on a hand-held Sony monitor. Gregg’s beautiful hair keeps falling in his face and has to be shaken back. East of the Courthouse, the Arch soars above a planted grove of ash trees. I once wrote a novel that was centered on this monitory stainless icon of my childhood, I once invested the Arch and the counties that surround it with mystery and soul, but this morning I have no subjectivity. I feel nothing except a dullish anxiousness to please. I’m a dumb but necessary object, a passive supplier of image, and I get the feeling that I’m failing even at this.

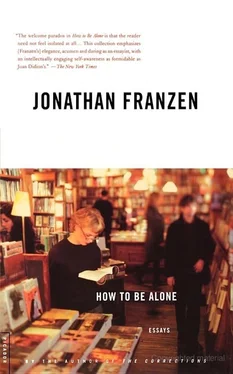

My third book, The Corrections —a family novel about three East Coast urban sophisticates who alternately long for and reject the heartland suburbs where their aged parents live — will soon be announced as Oprah Winfrey’s latest selection for her televised Book Club. A week ago, one of Winfrey’s producers, a straight shooter named Alice, called me in New York to introduce me to some responsibilities of being an Oprah author. “This is a difficult book for us,” Alice said. “I don’t think we’re going to know how to approach it until we start hearing from our readers.” But in order to produce a short visual biography of me and an impressionistic summary of The Corrections the producers would need “B-roll” filler footage to intercut with “A-roll” footage of me speaking. Since my book-tour schedule showed a free day in St. Louis the following Monday (I was planning to visit some old friends of my parents), might it be possible to shoot some B-roll in my former neighborhood?

“Certainly,” I said. “And what about filming me here in New York?”

“We may want to do that, too,” Alice said.

I volunteered that between my apartment and my studio in Harlem, which I share with a sculptor friend of mine, there was quite a lot of visual interest in New York!

“We’ll see what they want to do,” Alice said. “But if you can give us a full day in St. Louis?”

“That would be fine,” I said, “although St. Louis doesn’t really have anything to do with my life now.”

“We may want to take another day later and do some shooting in New York,” Alice said, “if there’s time after your tour.” One of the reasons I’m a writer is that I have uneasy relations with authority. The only time I’ve ever worn a uniform was during my sophomore year in high school, when I played the baritone for the Marching Statesmen of Webster Groves High School. I was fifteen and growing fast; between September and November I got too big for my uniform. After the last home game of the Statesmen’s football season, I walked off the field and passed through crowds of girl seniors and juniors in tight jeans and long scarves. Dying of uncoolness, I tugged down my tuxedo pants to try to cover my ridiculous spats. I undid the brass buttons of my orange-and-black tunic and let it hang open rebelliously. I looked, if anything, even less cool this way, and I was spotted almost immediately by the band director, Mr. Carson. He strode over and spun me around and shouted in my face. “Franzen, you’re a Marching Statesman! You either wear this uniform with pride or you don’t wear it at all. Do you understand me?”

When I accepted Winfrey’s endorsement of my book, I took to heart Mr. Carson’s admonition. I understood that television is propelled by images, the simpler and more vivid the better. If the producers wanted me to be Midwestern, I would try to be Midwestern.

On Friday afternoon, Gregg called to ask if I knew the owners of my family’s old house and whether they would let a camera crew film me inside it. I said I didn’t know the owners. Gregg offered to look them up and get their permission. I said I didn’t want to go in my old house. Well, Gregg said, if I could at least walk around outside it, he would be happy to get permission from the owners. I said I wanted nothing to do with my old house. I could tell, though, that my resistance displeased him, and so I offered some alternatives that I hoped he might find tempting: he could shoot in my old church, he could shoot in the high school, he could even shoot on my old street, provided he didn’t show my family’s house. Gregg, with a sigh, took down the names of the church and the high school.

After I hung up, I became aware that I’d been scratching my arms and legs and torso. I seemed, in fact, to be developing a full-blown bodywide rash.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу