Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

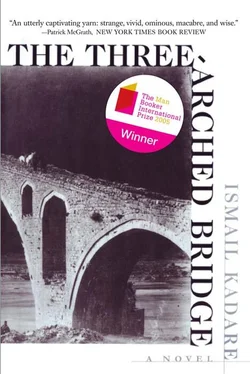

- Название:Three Arched Bridge

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Arched Bridge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Arched Bridge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Three Arched Bridge — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Arched Bridge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We were on the brink of war, and only the blind could fail to see it. Since the Ottoman state became our neigh, bor, I do not look at the moon as before, especially when it is a crescent, No empire has so far chosen a more masterful symbol for its flag. When Byzantium chose the eagle, this was indeed superior to the Roman wolf, but now the new empire has chosen an emblem that rises far higher in the skies than any bird. It has no need to be drawn like our cross, or to be cut in cloth and hoisted above castle turrets. It climbs into the sky itself, visible to the whole of mankind, unhindered by anything. Its meaning is more than clear: the Ottomans will have business not with one state or two states, but with the whole world. Your flesh creeps when you see it, cold, with sometimes a honey-colored and sometimes a bloody tinge. Sometimes I think that it is already bemusing us all from above. There is a danger that one day, like sleepwalkers, we will rise to walk toward our ruin.

Last night as I prayed, I unconsciously replaced the words of the holy book, “Let there be light,” with “Let there be Arberia!” almost as if Arberia had in the meantime been undone…

I myself was terrified by this inner voice. Later, when I tried to discover from whence it came, I recalled all kind of discussions and predictions now being made about the future of this country, Arberia will find itself several times on the verge of the abyss. Like a falling stone, it will draw sparks and blood. It is said that it will be made and unmade many times before it stands fixed for all time on the face of the earth, So’ let there be Arberia!

56

DESPITE THE GREAT FROST, there are Turkish troop movements on the borden The drums are inaudible, but their banners can be discerned from a distance.

One morning’ sentries of the principality appeared at both ends of the bridge. Our liege lord’s estrangement from the neighboring pasha had deepened.

The armed guards remained at the bridge day and night’ next to the signs with the tolls. We thought this must be a temporary measure, but after three days the guards were not withdrawn but reinforced.

Dark news came from all sides. Old Balsha had gone completely blind’ night coming to his eyes before his soul. As the saying goes, “May I not see what is to come!”

57

MEANWHILE, as if not caring about what was happening throughout the Balkans, travelers whose road brought them this way, or rich men journeying to see the worlds paused more often at the bridge. This had become so common recently that the landlord of the Inn of the Two Roberts had placed a kind of notice at both his gates, written in four languages: “For those guests desiring to see the famous Three-Arched Bridge, with the man immured within’ the inn provides outward and return journeys at the following rates …” (The tariff in various currencies followed.)

A large cart drawn by four horses and equipped with elevated seats carried the guests to and from the bridge two or three times a day and sometimes more often. Loudmouthed and boorish, as idle travelers usually are they swarmed around and under the bridge, noticing everything with curiosity, touching the piers, crouching under the approach arches, and lingering by the first arch where the man was immured. Their polyglot monotonous, and interminable chatter took over the site, I went among them several times to eavesdrop on this jabbering, which was always the same and somehow different from the previous day’s. The flow of time seemed to have stood still. They talked about the legend and the bridge, asked questions and sought explanations from each other, confused the old legend with the death of Murrash Zenebisha, and tried to sort matters out but only confused them further, until the cart from the inn arrived, bringing a fresh contingent of travelers and taking away the previous one. Then everything would start again from the beginning. “So this whole bridge was built by three brothers?” “No, no, that’s what the old legend says. This was built by a rich man who also surfaces roads and sells tar. He has his own bank in Dürres.” “But how was this man sacrificed here, if it’s all an old legend?” “I think there is no room for misunderstandings sir. He sacrificed himself to appease the spirits of the water, and in exchange for a huge sum in compensation paid to his family.” “Ah, so it was a question of water spirits; but you told me it had no connection with the legend.” “Pm not saying it has no connection, but… the main thing was the business of the compensation.”

And then they would begin talking about the compensation whistling in amazement at the enormous sum, calculating the percentages the members of his family would earn from the bridge’s profits, and converting the sums into the currencies of their own principalities, and then into Venetian ducats. And so, without anyone noticing, the conversation would leave the bridge behind and concentrate on the just-arrived news from the Exchange Bank in Durres, particularly on the fluctuating values of various currencies and the fall in the value of gold sovereigns following the recent upheavals on the peninsula, And this would continue until some traveler, coming late to the crowd, would say: “They seemed to tell us that it was a woman who was walled up, but this is a man. They even told us that we would see the place where the milk from the poor woman’s breast dripped,“ “Oh,” two or three voices would reply simultaneously, “Are you still thinking of the old legend?”

And it would all go back again to the beginning.

58

IT WAS MARK HABERI who was the first to bring the news of the Turks, “commination” against Europe from across the border, Pleased that the event seemed so important to me, he looked at me with eyes that reminded me of my displeasure at his change of surname, almost as if, without that Turkish surname, he would not be able to bring news, in other words habere , from over there.

Indeed, his explanation of what had happened was so involved that while he talked, he became drenched with sweat, like a man who fears to be taken for a lian Speak clearly, I said to him two or three times, because I cannot understand what you are trying to say. But he continued to prevaricate. I can’t say it, he repeated. These are new, frightening things that cannot be put into words.

He asked for my permission to explain by gestures, making some movements that struck me as demented. I told him that the gesture he was making is among us called a “fig,” and indicates at the same time contempt, indifference, and a curse. He cried, “Precisely, Father. There they call it a ‘commination, and it is of state importance.”

I did not conceal my amazement at the connection between this hand movement, which people and especially women make in contempt of each other, somewhat in the sense of “may my ill fortune be on your head,” with the new Ottoman state policy toward Europe, of which Mark Haberi sought to persuade me.

He left in despair to collect additional data, which he indeed brought me a few days later, always from the other side. They left me openmouthed. From his words and the testimony of others that I heard in those days, I reconstructed the entire event, like a black temple.

The Commination against Europe had taken place in the last days of the month of Michaelmas, precisely on the Turkish-Albanian border, and had been performed according to all the ancient rubrics in the archives of the Ottoman state. Their rules of war demanded that before any battle started, the place about to be attacked, whether a castle, a wall, or simply an encampment, had to be cursed by the army’s curse maker.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Arched Bridge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.