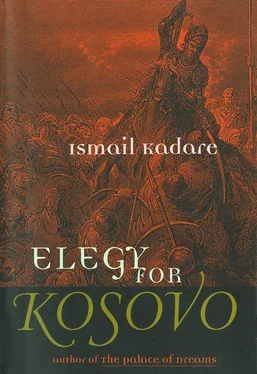

Ismail Kadare

Elegy for Kosovo

Never before had rumors of impending war been followed by rumors of peace. Quite the opposite — after hopes for peace, suddenly war would be declared, which was practically routine in the large peninsula.

There were times when the peninsula seemed truly large, with enough space for everyone: for different languages and faiths, for a dozen peoples, states, kingdoms, and principalities — even for three empires, two of which, the Serbian and the Bulgarian, were now in ruins, with the result that the third, the Byzantine Empire, was to its disgrace and that of all Christianity declared a Turkish vassal.

But times changed, and with them the ideas of the local people changed, and the peninsula began to seem quite constricting. This feeling of constriction was spawned more by the ancient memories of the people than by their lands and languages rubbing against each other. In their solitude the people hatched nightmares until one day they felt they could no longer bear it.

This usually happened in the spring, when, along with the whispers of war or peace, there was a feeling of inexplicable tension in the air. In fact, both the good and the bad prophecies never ebbed in the low-lying regions, particularly in the towns. But they tended to become a flood when they mingled with the anxiety of the mountain people. And this happened in the spring, right after the first signs of the snow melting. The explanation was simple enough: the predictions of the city people were based on information and rumors spread by itinerant merchants, consuls’ coachmen, spies, epileptics, and harbor prostitutes, and on the rate of exchange of Venetian ducats in the Durrës banks. Nonetheless, however reliable these sources of information might be, another dimension was necessary to authenticate such rumors, a dimension that was mysterious and intangible — in other words, irrational. This dimension was provided by the mountain people.

For the mountain people, everything from the Cursed Peaks of Albania and Montenegro to ancient Mount Olympus and the Carpathians was linked with snow. Just as the city people imagined a world that was basically flat, the people of the mountain pastures made the opposite mistake; they believed in the supremacy of the mountains. So even if somebody swore a solemn oath that he had seen with his own eyes an army ready for war, the mountain people would look up toward the snows and shake their heads. As long as the cherished snow still lay up there, no army was on the move, no war was about to begin.

In the spring this conviction was shattered, and with the melting snow thoughts changed.

This is what happened in that spring of 1389 when, right after the news that there would be a very special peace, there came other news that there would be war, and that this war would be very special indeed.

That spring the world was rife with rumors. No caravan transporting cheeses, no consul passing through could fill the emptiness — it filled itself spontaneously. People had also realized in recent years that where the roads were blocked by snow or plague, the whispers, instead of dying away, became even stronger. The reason seems to have been that the lack of fresh news made people turn to the past. The news of what had gone before, like old clothing, was easier to slip into.

In remote taverns they spoke of the Turks moving their capital from Bursa to Adrianople, as if the event had occurred the day before and not some twenty years earlier. And that the Turkish monarch was moving the capital, some said, in order to shift his empire to Europe. Others either refused to believe this or shook their heads in horror. Can one move an empire as if it were a house? Not to mention: Where would poor Europe find enough space for such a huge empire? The Turk doesn’t give a damn if it fits or not. “Move over!” he says. “Make room for me, or I’ll kick you out!”

Others, who did not want to believe that this calamity could come about, said that if the sultan was moving the capital nearer, it was perhaps so that it would be easier for him to keep an eye on the quarrels of the peninsula’s princes. “To keep an eye on our wrangling?” others objected incredulously. “Our wrangling is so deafening that there is no need to come closer — in fact you can hear it better from afar!”

The discussion about the quarrels of the native princes turned spontaneously to their secret alliances, particularly their bondage to the Turk. Of all the rumors, these were the most unsubstantiated. No sooner did word go around that King Tvrtko of the Bosnians had bowed down to the sultan, than other news came that it wasn’t King Tvrtko, nor Mirçea of Rumania, but Sisman, czar of the Bulgarians, who had knelt before the sultan. “I am not surprised about the Bulgarian czar,” an unknown man said, “but my soul aches when I call to mind Emperor John V!”

“Ah, Byzantium!” others sighed. “Byzantium, my friend! You have sinned and now you must pay the price.”

The news that people were wrangling not only here in this godforsaken part of the world but everywhere, even among the Turks themselves, was a consolation. Everyone was talking about the affair of the two princes, the Turk Cuntuz, son of Sultan Murad, and Andronicus, the heir of John V. While the fathers had formed an alliance and were busy waging war in Asia, the sons were conspiring to overthrow them. The fathers clapped them in irons, and Sultan Murad, in order to reaffirm his friendship with his Christian ally, had his treacherous son punished with the official Byzantine torture — blinding. And, needless to say, the Christian monarch reciprocated with his son.

Talking about the savagery of these two fathers reminded people of their evils and caprices. Many of these monarchs’ actions, which seemed to defy reason, were beyond understanding not because they were inscrutable but because of their inherent madness. The idea of moving the capital, for instance, might well have had a sound motive but was more likely the outcome of one of the sultan’s whims. With an empire of such boundless proportions, such whims were to be expected. Too often the great are permitted what lesser men are not. The Montenegrins might have liked to move their capital, Cetinje, but where would they have put it? Two miles over, and the wretched city would have landed in the talons of the Albanian eagle. The same goes for Skopje, and as for Sofia, God knows where it would have ended up! In Russia, probably, or in the Black Sea!

Twilight fell, and before the taverns closed and everyone wished each other a good night, the conversation turned to the latest piece of news — the Turkish monarch’s change of title. Until recently, he had been called “Emir,” but now he was going to be called “Sultan,” This was definitely a bad sign. The last time there had been a change was on the threshold of a war. Besides which, the title “Emir” sounded tender to all ears — in the languages of the southern Slavs the word mir means peace, while in the language of the Albanians it sounds like i mirë, good man, or e mirë, good woman.

“And yet, did he not slash us all to pieces under that title at the battle of Maricë?” someone asked as he put on a skullcap. “Slashed us to pieces, by God!” said another, scratching his head. “And not only the Serbs and the Hungarians, but also we Albanians who had rushed off to help them, and even the French king, Louis d’Anjou. It is where my lord Count Muzaka fell, may he rest in peace!”

“Sultan.” The people muttered the new title to themselves as if they were trying to fathom its secret.

Читать дальше