Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

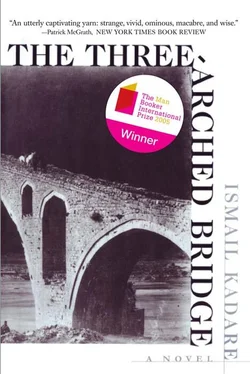

- Название:Three Arched Bridge

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Arched Bridge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Arched Bridge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Three Arched Bridge — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Arched Bridge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was the beginning of April The weather was fine, and work proceeded on the bridge more busily than ever before. The dead man seemed to spur the work forward. The second span was now completely finished, and the vault of the third was being raised. Last year’s filthy mud, which had dirtied everything round about, had gone. Now only a fine dust of noble whiteness fell from the carved stones and spread in all directions. It coated the two banks of the Ujana, and sometimes on nights of the full moon it shone and glittered in the distance.

On one of these moonlit April evenings I ran into the master-in-chief on the riverbank, quite by accident. I had not seen him for a long time, He seemed not to want to look me in the eye. The words we exchanged were quite meaningless and empty, like feathers that float randomly, lacking weight and reason. As we talked in our desultory way,1 suddenly felt a crazy desire to seize him by the collar of his cape, pin him against the bridge pier, and shout in his face: “That new world you told me about the other day, that new order with its banks and percentages, which is going to carry the world a thousand years forward, it is founded on blood too.”

In my mind I said all this to him, and even expected his reply: “Like all sorts of order, monk.” Meanwhile, as if he had sensed my inner outburst, he raised his head and for the first time looked me in the eye. They were the same eyes that I now knew well, with rays and cracks, but inflamed, as if about to burst, almost as if it was the fortieth day not for the dead man at the bridge but for himself….

41

SPRING WAS EXCEPTIONALLY CLEAR. The Ujana e Keqe brimmed with melted snow, Though full and renewed, the river mounted no attack on the bridge. It seemed not to notice it anymore. It foamed and roared around the stone piers and under the feet of the dead, but as it flowed on it spread out again, as if pacified by the sight of the victim. A wicked, mocking glint remained only in the cold crests of the waves.

All spring and at the beginning of summer, work continued busily. The third arch was almost finished, and work began on the right-hand approach arch,

Throughout its length the bridge echoed to the sounds of masons’ hammers, chisels, picks, and the creaking of the carts. Amid the constant din of the building work and the roaring of the river, Murrash Zenebisha stood, coated as ever with plaster, solitary, white, and alien. Whether the flesh of his face had decayed under his plaster mask, or whether it had hardened like mortar, nobody could tell

His family came as always, but gradually reduced the length of their visits. Some days after his immurement, stunned by everything that had happened, they remembered that they had not even managed to weep for him according to custom. They tried to do so later, but it was impossible. Their laments stuck in their throats, and the words that should have accompanied their weeping somehow would not come. Then they tried hiring professional mourners, but these women too, although practiced in weeping under all kinds of circumstances, could not mourn, try as they might. He does not want to be wept for, his parents said*

Some time had passed since his death, and at times it seemed a source of joy to his family that they would have his living form in front of their eyes, but sometimes this seemed the worst curse of all Now they no longer came together, His wife would come alone with her baby in her arms and, when she saw the others approaching, would leave, People said that they had quietly begun to quarrel over sharing the compensation,

The investigators also came less frequently. It seems that the count had other worries and would have liked to close the inquiry. However, this did not prevent the fame of Murrash Zenebisha from spreading farther every day* It was said that he had become the conversational topic of the day in large towns, and that the grand ladies of Dürres asked each other about him, as about the other novelties of the season.

Many people set off from distant parts with the sole object of seeing him. Sometimes they — came with their wives, or even made the journey a second time. This was no doubt why the Inn of the Two Roberts had recently doubled its business.

42

THE WEATHER DETERIORATED. The count, together with his family, returned from the mountain lodge where he had spent the summer. At the bridge, the left-hand approach arch was being finished.

One day at the beginning of September the count’s daughter came to see the immured victim. I had not seen her for some time. She had grown and was now a fine girl. I thought she would not be able to bear the sight of the dead man, but she endured it. As she left the sandbank, thin and somewhat woebegone, people turned their heads after her. They knew that the powerful Turkish pasha, whom ill fortune had recently made our neighbor, had quarreled with our liege lord because of this dainty girl.

Perhaps because she had spent her girlhood in such troubled times as recent seasons had been, no tales had been woven around her, such as those about knights crossing seven mountain ranges to meet a girl in secret, and the like, which are usually told about young countesses and the daughters of nobles in general. In place of such tales of love, there was only an alarming sobriquet attached to her, which, I do not know why, spread everywhere, They called her “the Turk’s bride.” I often racked my brains to explain such an irrational nickname. It was quite meaningless, because nothing like that had happened. It was the opposite of the truth, but the nickname clung to her. It could not conceivably have been created out of goodwill, or even malice, and so perhaps resembled a truth and a lie at the same time. The girl did not go to the Turks as a bride, but the nickname remained, as if it were unimportant whether the wedding took place or not, and the main thing was the proposal and not its acceptance. And so she was called “the Turk’s bride” simply because the Turks had asked for her, had cast their eyes this far, and had brandished from a distance that black veil with which they cover their women.

The nickname made my flesh creep. Why was it still used, and why did it not perish the moment the Turk’s proposal was rejected? What was this perpetual danger, this offer of marriage, that still floated on the wind? Sometimes I told myself that it was a chance nickname, more ridiculous than alarming, and not worth becoming upset about, but it was not long before my suspicions were aroused again. Did it all not extend beyond the fate of the noble young lady? Did popular imagination in some obscure, utterly vague way perhaps foresee a generally evil destiny for the girls of Arberia? This horrible nickname could not have arisen for nothing, still less have stuck to her like a burr.

I said these things to myself, and thought: If only that young girl knew what I was thinking as she walks along the bank with her nurse, her slight figure almost translucent!

43

HASTE WAS EVIDENT EVERYWHERE: in the works on the Ujana, in the pace of the heralds, and even in the flight of the storks, which, having pecked at the beams of the bridge for the last time, set off on their distant migrations that no rivers or bridges obstructed.

Even the news coming from the Orikum base was gathered in haste and was contradictory. It was said that the aged Komneni was dead but that his death was being kept secret because of the situation at Orikum. All kinds of other things were whispered. It was said that the great Turkish sultan had withdrawn into the interior of Asia to meditate in complete solitude about the general affairs of the world, and that this was the reason why the Turks seemed to have fallen asleep.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Arched Bridge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.