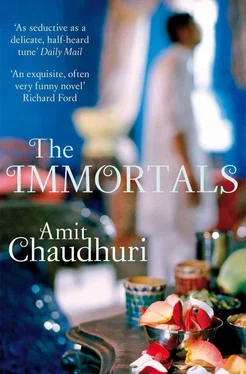

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

His own relationship with Shyamji was neither here nor there; he still hadn’t started taking regular lessons from him. For one thing, it wasn’t a traditional guru — shishya relationship; and this by mutual consent. When Mrs Sengupta had asked Shyamji, ‘Should you both go through the ritual?’ which would have meant the guru tying the nada, the thread, round the shishya’s wrist, and the shishya giving his teacher guru-dakshina, maybe a couple of hundred rupees and a box of sweets, Shyamji said, ‘There’s no need to tie the nada.’ Shyamji lived in the real world, not in some imagined idea of antiquity.

The boy was slightly disappointed, but relieved.

* * *

NIRMALYA HAD a maroon kurta, a dark blue kurta, and a deep green one; handwoven cloth from the spinning wheel. He wore them repeatedly. He wore them with white churidars or blue jeans — the simple clothes a complex uniform, denoting his emergence from the life he’d grown up in. He would have been nothing without them; they were as white or saffron robes are to a holy man — a sign of being removed from the world while being in it, and of allegiance to some order that gave him the vantage point from which to view the ways of ordinary people with distance and tolerance. His appearance exasperated his father, made a certain kind of person wary, and encouraged another sort of person. For instance, although he didn’t smoke, he was sometimes offered LSD by a whispering man (at once dropout and visionary) in a corridor when he went inside the college. Oddly, he actually still didn’t have a single vice, he wasn’t interested in smoking or drinking; but he had the unmistakable air of one who was drifting, of one who’d probably lost his bearings.

Meanwhile, his parents looked better and better — they were in their mid-fifties; they didn’t look older than forty. Nirmalya laboured on the meaning of life; he wondered sometimes about the point of existence, the purpose of the universe’s inscrutable journey; the universe seemed to him like a variety show on whose no single facet he could focus. He’d discovered a hollowness in the pit of his stomach; it made him feel exceptionally ancient, as if he’d been travelling for centuries. He was consoled by the sight of his parents; as they embraced life, and the company lifestyle, they grew visibly younger. ‘Life’s begun late for your father,’ said Mrs Sengupta to Nirmalya. Becoming director, then chief executive, had given Apurva Sengupta a new energy and youth; it wasn’t only that his hair had become magically black overnight, or that he was even more handsome than before; he viewed the future, every morning, with a renewed sense of responsibility. Nirmalya felt jaded; the world — the flat; the view from the balcony; Cuffe Parade — caused him pain. He looked unkempt, out of joint, next to his parents.

But, just occasionally, his father fell ill from hard work. He fell ill from sitting too much in the same position. He sat in his suit on the swivel chair, hands on the desk before him. Mr Sengupta glanced at the files, signed memos, held interviews, had ‘meetings’, and, intermittently, gave dictation. Through all this, he — although his mind was in many places at once — remained mostly immobile. One day, a sharp pain pierced his right arm. Gradually, at work and at home, he found he couldn’t move the arm; Nirmalya, who was eleven then, had stared engrossed at the expression on his father’s face as he tried to lift it. It was diagnosed as spondylitis; the executive’s bane, hours of sitting causing the vertebrae to bear down on a nerve, resulting in excruciating pain. It had happened a long time ago, but Nirmalya could remember it well: his father’s stunned look as he was divested of his suit and then his shirt, down to the vest in which Nirmalya often saw him at night. Two weeks of enforced rest at the Breach Candy Hospital, traction weighted down his neck; the executive’s bane — hard work, the business of making a company run and earn profits, frozen into the body’s prolonged immobility — quite different from an athlete’s exhaustion. Dyer came to see his Head of Finance lying on his back; Nirmalya’s father smiled at him, teeth gritted because of the traction. ‘It was the only way to get you to get some rest, A.B.,’ said the Englishman, his eyes sparkling. ‘But we need you back soon.’

‘Sedentary lifestyle’: it was at this time that these words permanently became part of Mallika Sengupta’s vocabulary. ‘Sedentary’ — no activity at all, it had seemed, but as dangerous, it was revealed, as the most risk-laden act, like mountain-climbing: a brush with mortality, even, while sitting unmindfully upon a chair. She could no longer feel safe or content simply because her husband was seated; death hovered by the seated man as much as, if not more than, it did swimmers at high tide or those who leapt out of aeroplanes for sport. To be seated was to be seeking danger.

Some of Mr Sengupta’s colleagues played golf; a dignified, slow, comradely way of deferring the end of life. Apurva Sengupta almost took it up himself; but could never summon enough enthusiasm, in the end, to see his initiation through, to arrive at dawn before an open space somewhere in the middle of a congested city and discover his companions growing more familiar, less interesting, as it became light. He seldom exercised; the company preoccupied him almost completely. But he was unscarred, as yet, by ‘the sedentary lifestyle’.

Soon after the regime of traction, and the disappearance of the pain, the freeing of his right arm, Mr Sengupta was up again, off to the office in his black suit in the morning. In the evening, he and Mallika Sengupta went out to parties as they used to; and their acquaintanceship with people who were extremely rich but had a wan, slightly deprived air, who owned roads and factories but whose houses were sparsely furnished, with barely a painting on the wall, whose names were a form of capital but who were themselves unprepossessing and anonymous, the immense diamond earrings on their wives’ earlobes always as much a surprise as the weathered walls of their sea-facing apartments — the Senguptas’ acquaintanceship with these vintage business families increased.

They went to the Poddars’ place, the famous family that built schools and hospitals and named everything after themselves. They found them deceptively ordinary, phantom-like, unremarkable.

‘Did you see the glasses in which they gave us sharbat?’ murmured Mallika Sengupta. ‘Beautiful silver glasses — they must be heirlooms.’ She spoke in a scandalised and disarmed tone, as if people who had so much money had no right to possess beautiful things.

The Breach Candy Hospital intruded upon their lives again. They thought of it as just another benign, well-oiled institution, strangely and courteously obedient to their needs as everything seemed to be to the top-drawer executive; another constituent of a generally friendly environment, from which patients and visitors alike returned like happy churchgoers. It hadn’t occurred to them it might be recalcitrant or unpredictable; that it might be witness to a small disruption to afternoons of burgeoning and leisure.

Chandu Prakash Mansukhani, well known everywhere in the nation for CP Tyres. A dashing new type, with a degree from Stanford; modest, confident, quite unlike the clumsy scions and elders of the old business families; someone you could have a brief conversation with at a party and discover that a smile lingered on your lips later — an aftertaste of rightness. It was that combination of things — affluence and taste, money and culture — that seemed destined for one another but were so rarely wedded. He, of all people, had had a chest pain in the afternoon. They — Apurva and Mallika Sengupta — had been to his house several times; two weekends ago, in fact, they’d come into contact with that measured, understated persona again, and marvelled at the rightness of its proportions without saying as much.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.