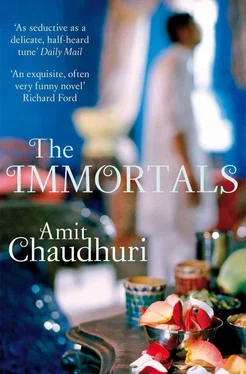

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Other pictures were purchased after they moved to this flat — and the cost put down to the ‘soft furnishings’ account. ‘Soft furnishings’ and ‘entertainment allowance’ — these were the two ways in which the company made up for what it couldn’t give its directors through the heavily taxed income, cocooning them from the brunt of the non-company world, making it, somehow, less urgent and real. Yet ‘soft’ — as if the fixtures, in a state of semi-fluidity, resisted the solidity of the Midas touch.

His mother went to the Cottage Industries, wandering aimlessly and liberally on its three levels amidst handicrafts and handlooms, children’s playthings made in remote regions of the nation scattered here and there like debris, the dolls limp with concealed life, the horses fished out of some imaginary battlefield and left stranded; she noticed some Moghul miniatures — figures on a white surface.

‘Madam, this is ivory,’ said the saleswoman apologetically.

Ivory! But wasn’t ivory illegal — Mrs Sengupta hardly saw it these days; it was like going down the tunnel of time and glimpsing something decadent and vanished. No, not illegal; but rare. Mrs Sengupta stared for a couple of moments at the figures: the woman in the brocaded top, the man in an ornate cap, the ageing man holding a rose, the small meeting inside a durbar.

The four miniatures were put down to ‘soft furnishings’.

The miniatures were hung up on one of the walls of the drawing room, not far from a wooden cabinet that housed the music system with its frozen turntable and the muscular wires at the back. Nirmalya guessed that one was Jehangir, the other figure Noor Jehan. The middle-aged person, his whole figure, from top to bottom, in profile, was clearly the Emperor Akbar; or so Nirmalya presumed from the man’s appearance. He seemed content, standing in the void of a clearing, pausing for a moment in what looked to Nirmalya like wintry daylight.

Standing alone in the half-empty flat, Nirmalya wondered if the nearest one could come to that kingly world was to be someone like his father — a Managing Director. He saw before him, in his mind’s eye, his father in his black suit, going out to the office. Did he feel some of Akbar’s poised contentment? Because Akbar, in that painting, standing indecisively, seemed not only to be looking, but listening to something. Did his father, too, secretly, listen to the world?

A woman called Shalini Mathur came to tinker with and reorganise the flowers in the vases twice every week. She was an expert flower arranger — she had a diploma in flower arrangement — and the company had hired her to do something pretty and slightly different with the flowers every few days in the Chief Executive’s flat; to involve these inert, fragrant objects in a delicately changing composition. Shalini came in at about ten thirty in the morning, and began to work; she smiled sweetly at no one in particular, and hardly said anything. She sheared the stalks, trimmed leaves; the vases were always surrounded, while she bent over them, by an autumnal precipitation of disposable plant-life. Pleasant but unremarkable to look at, with thin hair and the efficient but somewhat provisional air of a working woman, always in light chiffon saris that fell upon her like a rag, and rather unexpectedly large-breasted. When she spoke, she spoke to Nirmalya’s mother, briefly, and almost out of earshot. Nirmalya couldn’t remember having heard her voice.

She leaned forward to place the vases according to some tangible geometry of space, tangible only to her, like a web. The effect was a sort of Japanese calm. When she leaned, the dwarfed aanchal of her sari fell from place; her breasts were full and large.

Jumna, revealing her mauve gums, said, ‘She has very big “ball”. Look, look at Arthur — dekho isko, baba. He keeps leaving the kitchen and going into the drawing room.’ It was true. Arthur would shuffle out into the drawing room, look blankly about him for a few seconds, while Shalini, in the distance, a mixture of professional seriousness and divine obliviousness, hovered behind the flowers, and go back to the kitchen. ‘“Baap re, what big ball, what big ball!” he keeps saying,’ reported Jumna. And, having heard this report, Nirmalya too found himself gravitating towards the drawing room once or twice, casual and anonymous in kurta and pyjamas, with an air of high-minded absentness that recently-turned voyeurs have. Shalini neither acknowledged nor ignored him; her eyes remained downcast but weren’t steely or unfriendly. She didn’t bristle; she just stiffened slightly, almost imperceptibly as a plant might — partly out of respect for the fact that the ghostly passer-by lurking past was the Managing Director’s son; and partly. . it was something else that was never quite brought to light.

Arthur, with quick small hands (he was a tiny man, well below five feet), made food common in storybooks — cottage pie, pancakes, honey roast ham. But, because the Senguptas didn’t eat this kind of food regularly, he found himself with nothing to do. So he became a savant in the kitchen, and browbeat the other servants. ‘Don’t throw them away!’ he ordered Jumna, after the flowers Shalini had arranged had shrivelled up, and were gathered funereally from the vases. He fried the petals diligently in masala and oil, and sometimes the servants had no other lunch. ‘Do you know what he gave us to eat today?’ complained Jumna to Mrs Sengupta one afternoon. ‘Flowers. Phool. I can’t eat them,’ she said glumly, and stuck out a bit of pink tongue. ‘They’re bitter.’ ‘Flowers?’ asked Mrs Sengupta, astonished. ‘Why?’ ‘He says they’re good for you.’ ‘But you can’t give them flowers, Arthur,’ said Mrs Sengupta gently; the old man nodded, his graven, bespectacled face, whose features were quite perfect, expressionless. It was true he was remarkably agile at seventy-four. He believed in the virtues of flower and root.

He knew some English; this made him comic and grand in everyone’s eyes, and almost incredible, like a member of the British royalty. One day, when Nirmalya had gone to the Dyers’, Matthew had told him, ‘Arthur’s made a chocolate cake for Tina’s birthday.’ ‘Really?’ said Nirmalya. ‘Yes, I’ll show it to you.’ He took the boy to the kitchen. He opened the fridge and showed Nirmalya a large cake on the second rack, spotlit briefly by the fridge’s light, chilled and sealed by its weather. In white, stylish icing, it had inscribed upon it ‘Happy Birthday Dina’. ‘But. .’ said Nirmalya. His mouth opened in an o. Matthew put a finger to his lips; he closed the fridge judiciously. Arthur called Dyer’s daughter ‘Dina’, and that was who she would be, for all purposes, this birthday.

Shyamji had no real interest in objets d’art; pictures of saints or gods or film stars he might take a second look at, but of art for its own sake he didn’t have a strong conception. But he was staring at the small durbar scene with interest: not necessarily because it was beautiful, but as if he recognised the people in it.

‘Did didi get this?’ he asked. ‘It is new, na?’

Nirmalya nodded.

‘Didi really has an eye for things,’ said Shyamji, looking about him, seeming to take in all the decorations in a glance. Then he became absent-minded, as if he were considering some distant object, something that wasn’t in the room. He waited for Mrs Sengupta to come out into the hall.

Nirmalya had become interested in this man: Shyamji. He still couldn’t quite make him out: he’d been observing him from a distance — and listening to him sing, of course. He came almost every other day to the flat; a man who was obviously a master of his craft, and who knew he was one. But not ill-at-ease among the furniture, the mirrors, the accessories to luxury; quite in his element, almost unconscious of his surroundings. Nirmalya was moved by his singing: it was like a spray of rainwater. The phrases were delicate and transient, and almost never, he noticed, sung in the same way twice. Shyamji’s ability to spin these beautiful musical phrases out of nothing, thoughtlessly — even, at times, callously, glancing quickly at his wristwatch — was, to Nirmalya, at once wonderful and perplexing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.