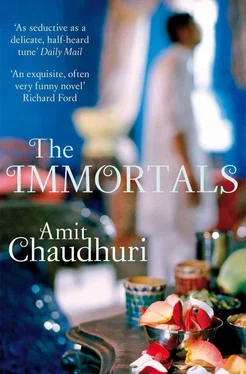

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Nirmalya had formed all kinds of ideas about art, about artists; although he could see that Shyamji was a great artist, he was trying to reconcile him to what his own idea of an artist was. Here was a man in a loose white kurta and pyjamas; a man who put oil in his hair. And, although his music sometimes sounded inspired to Nirmalya, a man who seemed to have no idea of, or time for, inspiration. A man who undertook his teaching, his singing, almost as — a job.

At sixteen, having recently entered Junior College, Nirmalya knew what he wanted to do. He had bought a copy of Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy ; he carried it with him on buses, occasionally reading or rereading a passage. He also possessed a copy of Being and Nothingness ; he’d never read beyond three pages in the introduction — they had taken him a week to read, the dense paragraphs were at once numbing and vertiginous — but the words in the title — ‘being’ and ‘nothingness’ — echoed in his head; they seeped into his thoughts. He’d recently become aware of the fact that he existed; and he wanted to get to the bottom of the fathomless puzzle of this new, undeniable truth.

Shyamji fitted neither the model of the Eastern artist, nor that of the Western musician. The Eastern artist was part religious figure, the Western part rebel; and Shyamji seemed to be neither. Shyamji wanted to embrace Bombay. He wanted to partake, it seemed to Nirmalya, of the good things of life; what he wanted was not very unlike what his father or his friends’ fathers wanted. Nirmalya couldn’t fit this in with the kind of person he thought Shyamji should be.

It was at this time he’d become interested in music; now, when he was poised between wanting to study philosophy, or economics (as his father and his relatives would have preferred him to). ‘Indian classical music’ — the rash of winter concerts in the city was where he’d discovered it; the oboe-like sound of the sarod, a musician in kurta and pyjamas crested upon his instrument; society ladies, saris dipping at the pelvis, the navel peering out with such a gaze of intimacy that he returned it in public; the husbands in silk kurtas, businessmen and executives, wearing ritual fancy dress: the mandatory pretence at being musical. Here, at these concerts, in the midst of this display, he went through the slow, private, educative process, full of humiliation and excitement, of identifying ragas; of mistaking one for another, of being moved by a melody he didn’t know. He stirred with recognition at the unmistakable ones, the ones with infallible preambles, Jaijaiwanti and Des; then, ragas like Puriya Dhanashree, with their seemingly antique inaccessibility — his ear began to domesticate them too; they remained mysterious, but became part of his life in the evening. Another discovery came to him with these — that very few people in the audience could tell one raga from another. In fact, the audience constantly threatened to come between him and the music; however sublime the music was, it was as if he couldn’t entirely enter its doorway because of his alienated awareness of other people. And yet, everyone, himself included, had, in one way or another, an air of proprietory wisdom about the proceedings. He sat there, appearing to look at no one, but actually noticing more than you’d have thought he had. Once, he’d spotted one of his father’s executive friends, whom he’d seen twice at a party at home, a head of a company, in a bright yellow kurta, quite unrecognisable. The man hadn’t seen Nirmalya. He went in a torn white cotton kurta and jeans whose bottoms were frayed and hung with threads; he glowered at the audience as he sat by himself.

Sometimes, he’d ask his mother to accompany him. ‘Ma, come on! I’m going to listen to Kishori Amonkar.’

‘Oh, all right!’ she’d say; secretly pleased. This honour he’d bestowed on her — his attention — was a recent development, a volte-face from the years of attention he’d demanded as a child. It was music that had brought about the change; a willingness now to share with her, whom he’d promoted without warning to the status of an equal, the phase of discovery.

He’d ignore her during the performance, hardly speaking to her. Sometimes, she’d fall asleep, tired after a bad night, calmed suddenly by the music. But they were united by the contempt they felt for the audience.

‘Look at these fools!’ she’d say.

She had the unimpeachable superiority, the spiritual unimpeachability, of one who was deeply gifted but whose gift was a secret. She pretended to be a chief executive’s wife, no more. She whispered in his ear, ‘This music is besura,’ when the sitar player hit a false note. And when she fell asleep — and this happened only when the music was at its most spontaneous and transporting — Nirmalya, although a little embarrassed, preferred his mother’s regression into this childlike, unconscious simplicity to the strenuous exhibition of appreciation by the people in the audience.

Later, after the performance and the applause, there was the long procession outward of smiling, redolent couples, the Deshpandes, Boses, Nanavatis, milling gently behind each other, readying themselves to return to appointed bedtimes and dinners, their pleased stupefaction at the music merging into their general air of contentment. Nirmalya and his mother — hardly aware, as she mingled with the people approaching the exit, of her own short slumber — might run into someone on the way out. ‘Ah, Mrs Sengupta!’ The tone was familiar, friendly, a little condescending.

The boy brooded in the background as the hall finally emptied, recognising neither the interlocutor nor his mother.

At first, he couldn’t understand the singing; the human voice was at once too intimate and foreign to listen to. But he found ‘instrumental music’ pleasant. At the same time, he was slightly repulsed by it. The sweet plucked and pulled notes of the sitar, the liquid rush of sound and excitement the tabla created: all these were already familiar to him — like a line from a poem taught in school that’s all but lost its meaning through study and repetition — from bucolic scenes in Hindi films, from government documentaries about road- and dam-building, even from close-up pictures of Mrs Gandhi cutting ribbons or welcoming foreign dignitaries. These images never quite left him, even when he thought he was wholly absorbed, attentive, listening.

The hall itself — whichever it happened to be — was a strange place; a part of the city, yet with its own weather, seasons, and an eternal daylight in which the audience, once the doors opened, trooped in and took their seats. It was this, perhaps, that made it possible, one day, for Ali Akbar Khan to play Lalit in the evening. The ageing ustad on the stage, struggling with his instrument, his bald pate almost like a sitar’s gourd, perfect; producing the notes of Lalit at six o’clock in the evening. A few people stirred uneasily. Nirmalya wasn’t unduly troubled; he knew, in an academic way, that Lalit was a morning raga, but he still couldn’t quite recognise it, and certainly hadn’t internalised it; he still didn’t associate Lalit with the first rays of daylight and a certain birdsong. Anyway, he couldn’t recall when he’d seen the first rays of daylight, and he didn’t care. A few people in the audience leaned over to each other and murmured, ‘Has the Ustad gone senile?’ The morning raga unfolded. The ustad’s face was calm like a Buddha’s, and stubborn as a child’s.

For two days afterwards, he carried this experience of Lalit in the evening inside him like something undigested. Is anything possible in 1980? he asked himself. After a few days, he told Shyamji what Ali Akbar Khan had done. Shyamji shook his head.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.