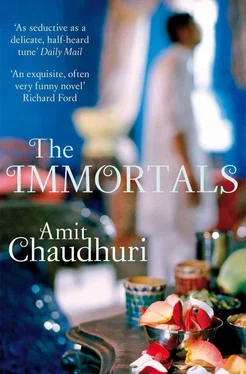

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One day he had chest pain and the next day he was dead. The doctor had said it was wind.

‘Isn’t it a shame. .’ said Mrs Sengupta, thinking of the warmth of that last meeting, a special intimacy which convinced them they knew him better than they did, ‘they live just opposite Breach Candy Hospital. If only. .’

No one was immune. Here was a man who belied that leaden word, ‘industrialist’. But he’d eluded them; he had only been forty-two.

‘The forties are a bad time,’ Mallika Sengupta said, looking up from a newspaper, compromised suddenly by fresh knowledge, and — she scared easily — a lurking fear. ‘Especially for businessmen.’ She went over her husband’s diet — though he was well past fifty — in her head.

Her own singing-practice was affected by the parties. She was being sucked into the vortex and extravaganza of the company Managing Directorship; swallowed, almost willingly, by its current. She couldn’t remember what she said at the parties; others’ remarks lodged themselves in her brain, but what she said herself she often didn’t know. At night, when she returned, she’d be seized by an obstreperous affection, and kiss her son several times where he lay sleeping, waking him up for a moment, although, in the mornings, he never had any memory of her swooping down on him so fiercely in her finery. And then she’d be too exhausted, after changing into her nightie, to take off her make-up, or even all the bangles on her arms; night after night, she’d fall asleep with her make-up on, the blush-on ruddying her fatigued expression, the kohl an outline against her closed eyelids. In the morning, when she sang, she had trouble with her voice; it wavered, weak with underwork, wreaking vengeance for the neglect. She grew impatient and thought, ‘I can’t sing any more. My voice has finally gone,’ although she knew this wasn’t true; that this was a justification, repeated to herself many times in the past, to escape a lifetime’s obsession and commitment and seemingly useless labour. And so she neglected it further.

Meanwhile, Nirmalya had plunged into the vocal exercises Shyamji had given him with the zeal of a convert, sitting on the durree-covered floor before the harmonium, pressing the key that gave him the sa with one finger, and chasing after perfection for about an hour. In a way, though he was a beginner, his situation was analogous to his mother’s — his voice wouldn’t obey him — but, unlike her, he had time and energy to spare. Because it could be like a battle; it required physical force to master the exercise. Afterwards, he felt, altogether, drained, satisfied, and defeated.

His transformation, noticed at first by the servants, had given him a mission. He exhorted his mother to get back to singing.

‘Ma, you’re not practising at all!’ he accused her as she slipped on a bangle. ‘You know what happens to the voice when you don’t practise!’ She, who had been singing for fifty years to his five months, looked at him with guilty eyes; she was nervous at the way he sprang upon her. ‘You’re spending too much time at these stupid parties.’

‘I hate going to them. Your father says they’re an important part of his job.’

She was torn, at these moments, between two influences: her husband, whose wisdom she was guided by, and who, in a way, shaped her life, even her life as an artist; and her son, who’d temporarily assume the role of a guru, always expecting more from her — not more maternal love, but devotion to her art — than she could give, and who seemed to have quite different ideas (he voiced them urgently) from his father about the role singing should play in her existence. There was no quarrel between Nirmalya and Apurva Sengupta about this; they wouldn’t even have been aware of the difference of opinion — but while one wished to always listen to his wife sing, and that she should be heard, somehow, by a few others, the other wanted her — it was never clear in what way — to be true to her talent. She, in the middle of this, could take neither Apurva Sengupta’s comfortable faith nor her son’s impatience seriously; compromise was necessary to lead a life even as unreal as this on an even keel — compromise, which engendered but also tempered disappointment.

Shyamji continued to give her bhajans: these songs that had been written by people whose lives had been wrecked, transformed, by hallucinations. Meera, who’d left her husband the Rana, without sensible justification, it seemed, for the blue god. For her, Krishna was as real as — more real than — the next person. Going through all those rituals of waiting; of shivering at the touch of the wind in expectation of him — it was a form of madness, which she herself at once admitted and refuted by singing, ‘Log kahe Meera bhai bawri’; ‘People say Meera’s mad’. And that remote, unreasoning anguish now entered the drawing room as recreation, and faintly moved the singer ventriloquising Meera’s implausible longing.

These songs were made sweet by Shyamji’s tunes; and the sound of his harmonium gave them a habitation and background. The tunes were simple, on the whole undemanding, and sometimes he had a formula which he used to make two or three of them.

Mallika Sengupta’s voice, for what reason she didn’t know, had the rare devotional timbre. She was not religious; she loved life; but when she sang, the true note of religion and renunciation sounded in her voice, as if from the memory of another existence she’d led in some other world. Even now, when she was quite out of practice from the socialising in the evenings, something of Meera’s illogical desire came to life in her rather guileless singing.

He was friends with his parents. When they went to the Taj for their cocktails and dinners, he went with them in high spirits. Of course, he wasn’t invited; he said goodbye to them in the lobby in which everything shone. He couldn’t help feeling at home in five-star hotels; he’d known them since he was a child. He wandered about, untidy but at ease, a paradoxical master of the terrain; no one challenged him.

After twenty minutes, he walked out and down the wide steps, past the Sikh doormen who’d not long ago deferentially opened the doors of the Mercedes. He first went down the promenade, where couples were leaning against the balustrade toward the water; sometimes there were groups of male friends in limp but apparently unshakeable postures of lassitude, ten- or eleven-year-old soft drink or peanut vendors hoarsely engaged in enterprise; the old and the new Taj looked down at Nirmalya. ‘Mata pita se toont gaya jo dhaga’: Meera’s words in the bhajan, ‘The thread that tied me to Mother and Father has snapped’, could never come true for Nirmalya. He would be lost without his parents. All he had were these snatched hours of solitude: his parents, now, might have been in another city.

There was no part of the by-lanes around the Taj that was not alive; the pavement around the Salvation Army guest house, around Barretto and Shepherd’s, tailors, where his father had his suits made, around the antique shop. This coughing, whispering life frightened him, but he went out searching for it. The cheap hotels behind the Taj, with old doors and ancient lifts; the beggars, in a huddle of amputated limbs and beedis, beneath the Gateway of India — from there he went back past the Eros cinema all the way to the Gothic building where classical music recitals took place, and easy-to-ignore exhibitions; it was not far from his college; the pavement here was empty but lit.

A woman was sitting on the steps of the building, before a locked door. She was dressed like a fisherwoman; a basket next to her contained clusters of bananas piled on top of one another.

‘Come here,’ she was saying. Her teeth were betel-stained; she smelled strongly of drink; it was like a gust — a soft, sour mist. Although he’d seen women drinking at parties, he couldn’t remember alcohol on a woman’s breath before; he was modestly shocked. She was smiling at him with a desolating expectation; she didn’t seem to recognise him for what he was, or at all care: his gentleness, his background, which she could never imagine, his upbringing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.