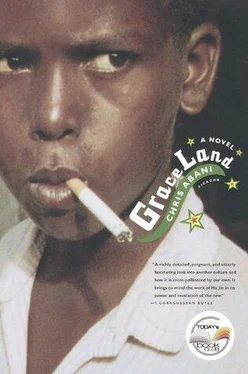

Elvis stubbed out his cigarette and settled back. Listening to the clack, clack of the palm fronds form a percussive background to the oboe throb of the sea, he dozed off. An hour later, he woke with a start and, standing up, dusted off the seat of his trousers. White sand, in fine glittering silicon chips, clung to him, catching the sun, turning him into a patchwork fabric of diamonds and ebony.

FRIED OKRA AND SWEET POTATO

INGREDIENTS

Sweet potatoes

Olive oil

Strips of beef

Okra (chopped)

Ose mkpi (fragrant yellow chilies)

Fresh plum tomatoes

Onions

Tomato puree

Maggi cubes

Salt

Ahunji

PREPARATION

Peel and slice the sweet potatoes thinly. Heat some olive oil. Salt the slices of sweet potato and drop into the oil when hot. Fry until crisp on the outside but soft and powdery on the inside.

Heat some oil in a wok and drop in the beef Sauté the meat for a while until brown and then add the rest of the ingredients. Fry until okra is a little brown around the edges, but still crunchy. Serving suggestion: arrange the slices of sweet potato in the shape of a flower; scoop the okra into the middle.

There is peril in this, and the loss of face is not only on the young neophyte, it is on his clan, as they have not taught him well.

Igbo clans comprise close kin who settled in clusters. All rights to land and ascendancy are determined by age, with the older males taking precedence. Likewise, the clan descended from the oldest relative in the cluster takes precedence over the others.

Lagos, 1983

Joshua Bandele-Thomas was measuring the barricades at one end of the street. He stopped, muttered something and made little notes in a worn leatherbound book. Counting off ten steps, he stood away from the barrier and set up his surveyor’s tripod. He bent and trained it on the barrier. Muttering even more, he made notes again.

Sunday watched him and shook his head. Crazy bastard, he thought.

Freedom and the boys had done a pretty good job. The barricades, made of broken furniture, old car skeletons, poles, building debris and other junk, were very secure. There was no way a small vehicle could get past them, much less a bulldozer. Besides, they were three deep. He turned round and watched Freedom directing the boys building the second set of barricades at the bottom of the street, arms waving, head bobbing like a conductor putting an orchestra through its paces. The children responded, laughing at Freedom’s high-pitched squeals and commands.

Sergeant Okoro walked over to Sunday.

“What do you think?” Sunday asked him, nodding in the direction of the barriers.

“I think dey are okay. Dey won’t keep dem out for long, though. Dey will bu’doze dese barricades in ten minutes.”

“Ever de optimist. We were considering placing ourselves between de barriers and de trucks.”

“Dat will only slow dem down. You cannot stop dem.”

“I don’t think any of us are being naive enough to believe we can stop dem. We are only hoping to delay dem for a while. Until de press can make a big story about it.”

“You call press?”

“No, but we dey hope say de story will attract dem.”

“Fine, because you cannot stop dem.”

“Yes, sure,” Sunday said, walking away.

Joshua Bandele-Thomas came over and stood beside Sunday. “De measurements do not compute.”

Sunday looked at him and shook his head. Joshua, his next-door neighbor, was an eccentric who modeled himself entirely on the classic Jeeves-and-Wooster English gentleman. He wore three-piece suits whatever the weather. For years he had worked as an accounts clerk for the Upanishad Tagore Company, eking out a sedentary and pedestrian existence. But he harbored a not-so-secret ambition: he wanted to go to England and study to be a surveyor. So he scrimped and saved, allowing himself only the luxury of elocution lessons. Unfortunately, the only teacher he could afford and still save enough to go to England was an old Spaniard who had come to Nigeria in the 1920s and stayed. Joshua was quite a character with his three-piece suits, bowler hats and Spanish-accented English.

Some years before, thieves had broken into his room and stolen his life savings, which were hidden inside his mattress. That marked a turning point in Joshua’s life. Instead of the mad ranting or raving Sunday had expected, he was quite calm about it. The only apparent difference was that he ate less and spoke only when spoken to. He had been stabbed in the eye during the attack, as he fought to keep his money, and his employer had graciously paid for a glass eye. Joshua accepted the gift gratefully and went back to work at the UTC a week later. Everyone thought he was fine. In fact the neighbors were admiring and spoke complimentarily of him in his absence.

Then one day someone saw him down at the marina on Lagos Island. He was wearing his three-piece suit, but he had substituted his bowler for a hard hat. He also had a surveyor’s level mounted on a tripod. He was causing a minor traffic jam as he went about carefully surveying the area, trailing an extra-long tape behind him. Sunday had caught a bus and gone down to bring Joshua home, and when he broached the subject of the surveying, Joshua responded merrily, “Why ju ask, Mr. Oke? Ju want a survey?”

Sunday had looked at him the same then as now, sadly. Madness was a terrible thing.

“The measurements do not compute,” Joshua repeated to Sunday, popping out his glass eye casually and rubbing the irritated socket.

Sunday nodded and looked away quickly. He knew what was coming next. Joshua cleaned the glass eye by sucking on it for a few minutes and popping it back in, still wet. Sighing, he went off down the street to measure the second set of barriers.

When the barriers were ready, Freedom sat on the floor by the last one with his exhausted troop of boys. Each one held a sweating cold bottle of Coca-Cola as they laughed and horsed around. Confidence, Okoro, Sunday and some other men from the neighboring tenements lounged on the steps drinking palm wine and chatting in somber tones. There had been some worry that the neighbors would not join them in the protest. The night before, however, employing the campaign tactics that hadn’t worked for him during the elections, Sunday had gone from tenement to tenement, home to home, across Maroko, speaking to the men and women he thought would have the most influence over their neighbors. Instead of the resistance or even apathy he had expected, nearly all had responded positively and had come out in force to help construct the barricades and assist in other ways.

“Gentlemen, Confidence has prepared de placards and banners,” Sunday announced.

The men crowded round as Confidence unrolled each one. There were twenty banners in all, and the four slogans had been repeated at random. WE OWN THIS LIFE; FREEDOM; RIGHTS TO EXPRESS; NO SA CRED cows. They were all done on old, stained brown-once-white sheets donated by the local clinic located a few blocks away. The doctor who ran the clinic was of dubious qualifications, and his nurse was his wife. After watching footage of the war-crime trials in Nuremberg in the cinema, everyone referred to him as Dr. Mengele. To ensure their plan did not leak, Sunday had asked Sergeant Okoro to stay back from work — not that he did not trust him, but one could never be sure what kind of pressure could be brought to bear on a man.

The police came at seven a.m., no doubt hoping to catch the street unawares. Everyone had been awake for hours, though, waiting tensely. Unsure how many policemen there were, Freedom instructed his boys to run from barricade to barricade, setting the first line alight.

Читать дальше