“But dere are too many entrances to Maroko.” Sunday said. “We cannot block dem all.”

“But dere is only four dat a bu’dozer can use,” the King said. “Your street here, which has two entrance, and Lawanson Street, which has two.”

As the King spoke, Elvis visualized the two streets. The King was right; they were the only two streets with outside access wide enough for any kind of vehicle except a bicycle or a motorcycle. He saw them spread out across Maroko in an uneven cross — a cross that would be held down at each end by human sacrifice, if they did what the King suggested. From the sky, he imagined, the streets must look like two straps straining to keep everything inside the bulky, unwieldy square of the ghetto.

“So simple it might work,” Okoro said doubtfully.

“But what if dey decide to drive through us?” Jagua Rigogo asked the question on everyone’s mind.

“They wouldn’t, would they?” Elvis asked.

“Whatever else dey may be,” Madam Caro reassured them, “dey are human.”

“I’m not so sure,” Sunday mused, looking at Okoro, who looked away guiltily.

They quickly ran through the plan. Confidence would paint placards using slogans devised by Jagua. Sunday, Madam Caro and Confidence’s wife, Agnes, would go and talk to people to try and mobilize enough of them to attend the street blocking the next day. And the King would lead them.

“I am sorry, but I cannot,” the King said.

“Why can’t you lead? It was your idea,” Confidence asked.

“I dey leave town dis evening with my band, de Joking Jaguars. We dey go tour and we no go return for at least two weeks,” the King replied.

There was a lot of loud dissension, but the King was adamant.

“Why you no lead?” the King asked Sunday.

“Me?”

“Yes, you,” everyone agreed, all desperate to have a leader that was not them.

“All right, if it is de will of de people,” Sunday said.

On the veranda, Elvis groaned to himself. What a fake old fart, he thought. But the conversation had moved on now that a leader had been identified. It was decided that the children would join their parents on the picket line as a guarantee that the police wouldn’t stampede them. Confidence did not like it. What if one of the children got hurt? He was prepared to let his children join, but he felt he could not ask the same of the other parents. He was outvoted and Freedom was put in charge of mobilizing the local children, as he was so good with them. They were to lug old tires, broken furniture, and empty petrol drums — anything they could find — and build an effective barrier that the police could not bridge. These, the King told them, could also be ignited to create a wall of flame to further frustrate the police assault that was bound to follow their resistance.

“Build dem three by three,” the King instructed.

“Three by three?” Freedom asked.

“Three walls, three feet apart, three feet thick.”

“Dat’s three by three by three. Ju don’t know your math,” Joshua said, looking up from his calculations.

Everybody glared at him.

“Sorry,” he mumbled.

Elvis had hung around wanting to talk his father out of leading what he was sure would be a suicide mission, but the insistent blaring of a car horn pulled his attention away from the meeting. Looking up, he saw it was Redemption, waiting for him in the Mercedes they had stolen from Ibare. As he ambled across the street, he saw that the King had beaten him to it and was talking to Redemption through the open driver’s window. As he got closer, he also noticed a soldier in full uniform sitting in the front passenger seat. It was Jimoh. The last time Elvis had seen him was the night the Colonel had almost killed him at the night club. He hesitated for a minute, but Redemption signaled him over frantically.

“Why you never come see me, Elvis?” Redemption asked as Elvis approached.

“I just woke up.”

“Dis Elvis, you are something, sleeping at a time like dis.”

The King had moved when Elvis came across, and now stood slightly to the left, watching.

“Why are you still driving this car?”

“Dat is small problem. Remember dis man?” he said, pointing at the uniformed soldier sitting next to him.

Elvis nodded. “It’s Jimoh.”

“De Colonel send him to tie up de loose ends.”

“What do you mean?”

“De Colonel send me to kill both of you,” Jimoh said.

Unconsciously, Elvis stepped back from the car. Overhearing, the King stepped forward, his hand on Elvis’s back, steadying him. Bending to look through the car window, the King spoke to Redemption.

“So what is de plan?”

“Me, I no get plan. I go dey dis town, I no fit run. In a few weeks de Colonel go forget us and everything go quench,” Redemption replied.

“But you get to live dat long first,” the King said.

“For me dat no be problem, but I worry for Elvis.”

“I fit help Elvis. My troupe dey leave town today to tour de country. He can follow me. By de time we return, everything go done cool down.”

“Dat’s good,” Redemption said. “Elvis, you dey hear?”

Elvis nodded. Redemption reached into his back pocket and pulled out an envelope, which he handed to Elvis.

“Elvis, dis na de money. You understand?”

“Yes,” Elvis replied, taking the envelope and shoving it into his back pocket.

“Chief,” Redemption said, turning to the King and handing him a handful of money. “Dis na for you.”

“Don’t insult me, Redemption. I no dey do dis for money.”

“I know. But I know as things hard for you. Take it.”

Reluctantly the King took the money and pocketed it.

“Elvis,” Redemption said.

“Redemption.”

With a hearty laugh, Redemption drove off and Elvis and the King crossed the street, headed back for the veranda.

“Listen, Elvis, we dey leave from in front of my place by six dis evening. Get your things and be ready.”

“Sure,” Elvis said. He stopped halfway across the street and turned to the bus stop.

“Where you dey go?” the King asked.

“To think.”

“My place at six. We no go wait,” he shouted after Elvis.

Elvis rode the bus down to Bar Beach. Getting off, he trekked across the sand, past the tourist beaches with pink expatriates baking slowly in the sun, past the mangy horses, the photographers with monkeys, the kebab, soft drink and food hawkers, through a coconut-palm thicket to a deserted beach. He sat, legs pulled to chin, gazing out at the ocean, watching giant waves crash against the shore. Elvis felt as if he were locked in a time warp, a suspended existence. The sea and the sky blended into one, and the background of sand, hardy grass and coconut palms sealed everything in completely, and the crashing sea became a dull throb in the background.

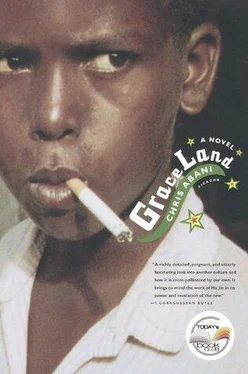

He chain-smoked, thinking about the children he had almost led to their deaths. He kept hearing Kemi’s voice, begging not to be killed. Watching the breeze playing through the leaves of the coconut palms, he wondered if Redemption had lied to him, if he had really known all along what the deal was. How could Redemption lead him down such a path? Now he had to flee from the Colonel, lay low for God knew how long.

It was kind of the King to offer to take him with his touring group, but things were happening here, and part of him wanted to stay and face the Colonel. Jimoh, however, had been clear: he had orders to tie up loose ends, which Redemption pointed out meant killing them. His own cowardice surprised him. He always thought when the moment came he would do the right thing. But going with the King also presented him with another opportunity to dance. The Joking Jaguars, the King’s performance troupe, was composed entirely of musicians and dancers. He missed dancing, and here was a chance to get back into it. The music would be highlife or jazz, he knew, and he probably wouldn’t get to do his Elvis impersonation, but he was still a good dancer regardless. And there would be an audience, one that had paid to see them perform. He had never had that, only bored and disgruntled passersby who felt his street performing was little more than begging, harassment even.

Читать дальше