You open your eyes to see yourself dreamed.

No, you have only said an ancient, unknown, Arabic word: orange tree. The survivors left through the walls of Numantia and could no longer speak. By saving themselves, they died. They were animals without language. That was their defeat, their death. And you, Scipio Aemilianus, you don’t know, now that you’ve died, what you already knew when you were a boy filled with hopes about the future of your life. Weren’t you going to be the one to reconcile and harmonize the power of your body by giving reasons to the sentiment that translated your animal power: to honor Rome? And how did you intend to do it if not through language? Isn’t this your most profound reason for living, young Scipio, old Scipio, dead Scipio? Use language well, the gift of the gods and of men. Reach poetry through public speech. Turn your life into an epic poem. Sing to Numantia, restore it to life with language. That which destroys the material thing constructs the work of art: light, wind, seasons, the passing of time. Save stone from stone and make it into words, Scipio, so that the very thing that eats away the stone — storm, time, sun — confers life — poetry, language, time.

You are dying, but you know at last that you will always be the master of language, which is the foundation of life and death on earth. Burn the earth there, the residence of language and death. For you, on the other hand, the world has died.

* * *

HE dreamed himself being dreamed. Cicero dreamed him, the greatest creator in the Latin language, seventy-five years after the mysterious death of Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, who won for himself the title of his grandfather, Africanus, and added to his dynasty a new title, Numantinus. Cicero honored him by dreaming him. By dreaming himself the day of his death, but also by seeing himself as a boy who dreams about heaven and eternal life. Such was the verbal monument Cicero erected to the man who best incarnated the qualities of the statesman and the philosopher in ancient Rome. Posterity’s monument to the ancient hero was to show him from the divine realm the composition of the universe: God made him see stars never seen from earth. Scipio recognized the five concentric spheres that, united, maintain the universe: Saturn, a hungry star; luminous Jupiter; red and terrible Mars; accommodating Venus and Mercury; Moon of reflections. Heaven embracing it all, in the center the Sun like a great orange in flames, and under everything a minuscule sphere and within it an even smaller empire, its scars invisible from on high, its wars and conquests whimpering with a voice of dust, its frontiers wiped out by waves of blood …

“What is that noise, so strong and so sweet, that fills my ears?”

Fame. It isn’t fame the hero hears from heaven. The universe is very large. There are distant regions of the earth itself where no one has heard the name of Scipio. The floods and conflagrations of the earth — natural, human — set about doing away with any personal glory. Who cares what those yet to be born say about us? Did the millions who preceded us say anything about us? Do you think that noise is fame, glory, war?

“If it isn’t,” asked the young Scipio, “is it the noise of reincarnation? Can we return to earth one day, transformed? Is Pythagoras right when he asserts that the soul is a fallen divinity, imprisoned in our bodies and condemned to repeat endlessly, circularly, a cycle of reincarnations?”

What ambition men have! God laughed on high. If they have neither glory nor fame, if they don’t have immortality, then they want to go through reincarnation. Why aren’t they content with living in heaven? Why don’t they listen to the celestial music? You have lost the ability to listen. Do you think that the vast movements of the heavens can be accomplished in silence? Men’s hearing has atrophied. Too concerned about what is said about them, they’ve stopped listening to the movement of the heavens. Look up, Scipio Aemilianus: learn now to look and to listen far off and outside yourself so you can finally reach yourself. Abandon glory, fame, and military triumph. Look up. You are rather better than the best you thought you were. YOU ARE GOD. You have what I have. Alert liveliness, sensation and memory, foresight as well, language and the divine power to govern and direct your body, which is your servant, in the same way God directs the universe. Dominate your weak body with the strength of your immortal soul.

And he, Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, listened then to the music of the spheres.

* * *

WE saw the fall of Carthage and the destruction of Numantia. They were glorious visions. But they only postponed our own defeat.

* * *

YOU will remember this story. The rest I leave to antiquarians.

Valdemorillo — Formentor, Summer 1992

NOTES

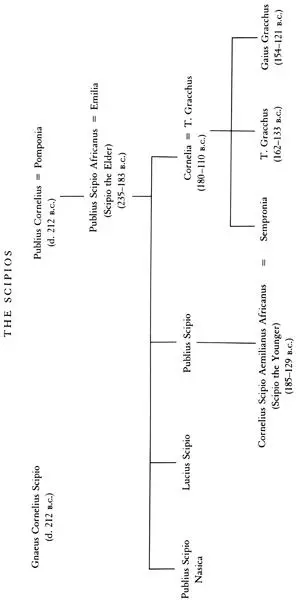

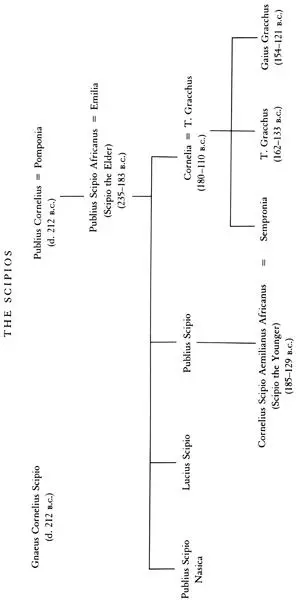

1. Genealogy: The brothers Publius Cornelius Scipio and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio fought against Hannibal in Spain and perished in the year 212 B.C. With his wife Pomponia, Publius Cornelius had a son, Publius Scipio, called Africanus because he defeated the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War (the battle of Zama, 202 B.C.). With his wife Emilia, Scipio Africanus had four children: Cornelia, Publius Scipio Nasica (consul in 162 B.C.), Lucius Scipio (praetor in 174 B.C.), and Publius Scipio, whose poor health kept him from taking up a political career. However, Publius Scipio adopted the younger son of Lucius Aemilius Paulus and his wife, Papiria, who were divorced shortly after the birth of the child, our protagonist, which took place in 185 or 184 B.C. He entered the Scipio family under the name Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus. His older brother, Quintus Fabius Maximus Aemilianus, was adopted by another family. Scipio Aemilianus captured and destroyed Carthage in 146 B.C. and conquered Numantia in 133 B.C. These two triumphs won him the titles “Africanus” and “Numantinus.” Thus there are two Scipio Africanuses: the Elder, the adoptive grandfather, and the Younger. Cornelia, the sister of Scipio’s adoptive father, was the mother of the Gracchi, leaders of the social reform movement of the year 133 B.C., which was opposed by their cousin Scipio Aemilianus, who died in 129 B.C. under mysterious circumstances. Rumor had it that he was assassinated by the followers of the Gracchi. Scipio Aemilianus was married to Sempronia, his cousin, the daughter of Cornelia and sister to the Gracchi. Did they have any children?

2. Bibliography: My principal sources regarding the life of Scipio Aemilianus and the siege of Numantia are: Appian, Iberica, book six of his History of Rome; Polybius, Histories; Cicero, “Scipio’s Dream,” in his Republic; and, of course, Miguel de Cervantes’s play The Siege of Numantia.

TO CARLOS PAYÁN AND FEDERICO REYES HEROLES, COMPANIONS ON AN INNOCENT TRIP

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you, And loved the sorrows of your changing face …

— W. B. YEATS, “When You Are Old”

Et le temps m’engloutit minute par minute …

— BAUDELAIRE, “Le Goût du Néant”

17:45

AS the Delta DC-9 begins its descent into the Acapulco airport, the instructions are announced by a voice so peaceful and polite that it seems hypocritical. Why don’t they tell us this is the most dangerous part of the flight — the landing? Up above, there are never any accidents. Unless the increasing congestion ends up multiplying midair collisions. I’m from California, so I know that Ronald Reagan cut off aid to the mentally ill, who then wound up in jails, as they did during the Middle Ages. He also devastated the air traffic controllers’ union. Maybe we’ll go back to traveling in caravels, while the planes smash into each other in the skies.

Читать дальше