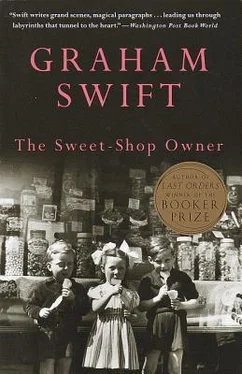

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Smithy would be the first to know. Smithy who had neither wife nor child. When the barber came in for his tobacco, he said, tilting his head confidentially: ‘I am going to be a father.’ Solemn, monumental words which didn’t hide the quiver in his voice. Smithy’s doughy face had creased. ‘Boy or girl?’ And he said — only realizing then he’d never assumed it would be otherwise — ‘Girl.’

November 10th, 1948. There was a red poppy in Smithy’s barber’s jacket and red poppies on the lapels of customers. Hancock would be wearing his Air Force tie and would comb with extra care his tawny moustache. And round the white memorial by the school railings, solemn, pink faces would reverently assemble. He bought a poppy from the seller outside the Post Office, but kept it in his pocket. Better rejoice. While there is time. Real flowers, not paper poppies. Red roses which he bought at the florist’s and carried home as a token.

But she didn’t seem glad. Her face showed only the pinched looks of someone labouring to pay a debt. So that he felt, through that lean winter of ’48, while her womb swelled, that he’d inflicted some penalty upon her for which he, in turn, must make amends by never showing gladness; taking her hint, leaving the house at six, standing obediently behind his counter: counting, counting the endless change so as to pay his own debt.

She took the roses and placed them, meticulously, in a vase, kissing him coolly on the forehead.

Yet her womb did swell. He put his hand on it and felt it, alive, inside. How palpable, how undeniable. But none of his pride suffused her. As if she were saying, as he laid his podgy, shop-stained fingers on her bigness, ‘Enough, don’t touch, don’t touch any more.’ ‘I can manage,’ she insisted, forcing a grin, as he rushed, playing to perfection his own part of anxious father-to-be, to take the shopping bag, the coal scuttle; ‘I’m not an invalid.’ But she carried around that weight inside her like something crippling, longing for but dreading the moment of release. March, April, May 1949. Visits to the doctor. With every month she seemed more the victim. So that when the moment came, precipitately — pink on the sheets, and him sitting on the edge of the bed, summoning the nerve to call a car — not even the words which he was forbidden to speak, which broke the terms of the bargain, could stop that drowning expression or the silent cry on her lips — Save me, save me.

‘I love you — keep still — I love you.’

It was her he looked at first; her and not the baby. Though he knew, as he stood there holding the flowers, that that little thing in a shawl in what looked like a wicker basket on a trolley beside the bed was their child. But he barely took in the fact, to look first at her. Expecting, perhaps, to see her changed, irrecoverable — or else restored completely. For this surely would be the moment: her or the child. But she was neither lost nor, it seemed, redeemed. She lay sleepily in the bed. Her face was soft, tired, but the lips firm. And there was that look, as she became aware of his presence: See, I have done it. See, I am a woman after all. That is my side of the bargain.

How warm it was. But should that window be open? A bee had flown in and was buzzing and tapping on the glass. With all those babies. Had nobody noticed? Sunlight was streaming in between the half-drawn curtains. There were pools of it on the parquet floor and on the white sheets of unoccupied beds. And, in between, wobbling with little unseen movements, these wicker baskets, like the fruits of some bizarre shopping trip.

‘The flowers. Give the flowers to the nurse.’

He stooped to kiss her but her eyes directed him to the baby. Before his lips could touch hers she had turned herself to where the rim of the wicker basket lay level with the bed, moved her mouth into a smile — it seemed she’d rehearsed with care that melting, motherly expression — and blown a kiss towards the little head in the shawl.

‘There. Look.’ She sank back.

A squashed-up, wrinkled face. Strands of dark, wet-looking hair. A mouth and tiny hands that seemed to protest feebly at some unpardonable imposition. But the eyes, when they opened, clear, grey-blue, were her eyes.

How simple to be the delirious father. To tickle the little body through the shawl, to chortle unlearnt baby-talk: ‘Hello. Goo, goo. Yes, yes.’ He didn’t look up at her — hadn’t her eyes said ‘The baby, not me’ — but he was aware of her, as she watched his antics, settling more firmly on the pillow, relieved, perhaps, by his simple glee, his compliancy, so that she could turn at last, having acquitted herself, to her old pose. She gripped the bed-clothes. Was she counting the violations of that pose? June 1949, in a delivery ward. June ’37 in a honeymoon hotel. Captured moments. And did she know to what she turned, there, in the hospital bed, steeling herself to the way the world looked from in there? Yes, I have made my forfeit, paid my price. But I will take the responsibility. And you will see, you will see it is for the best in the end.

Dorothy, you thought she didn’t have a heart. You never loved her. You merely suffered each other. And you thought I was her slave; she made a fool of me. But you never saw that look she gave me. How could you? And you never knew how I understood, then, how much she’d done for me. You were a little pink thing in a shawl. I was clicking my tongue at you and making absurd faces, and the nurse was smiling by the window, holding the flowers. There was a board clipped to your basket and a piece of paper with entries which read: Mother’s Name, Sex, Weight at Birth. Five pounds, twelve ounces. Pre-mature; but numbered, listed. When you grew up you wouldn’t go without milk and orange juice. The sun was shining outside on sycamore trees and railings, and a bee was buzzing at a window. You couldn’t have seen how she lay on that bed looking through both you and me as though she could see further than the two of us. But you will see.

They let me pick you up in your shawl. See, you can touch, take hold, after all. But the nurse looked mindful. ‘Your wife should rest now.’

Four days later they let you both come home. And that same month her asthma began again.

16

Sandra counted out change and shut the till.

‘Thirty, forty, fifty — one pound.’

It was approaching lunch-time and customers were multiplying. Outside, the shadows were heavy. Car-drivers leant against open windows in the slowly moving traffic. The pedestrians walking the hot pavement, jackets slung over shoulders, looked parched, in search of relief.

What absurdity. This endless succession of customers each after his little titbit. Papers, chocolates, cigarettes. You could remember faces by the things they bought. He was Gold Leaf; he was Hi-Fi News ; she was Brazil Nut. Mr Chapman was better at it than she, but then he had had more practice.

‘Two, three, four and one makes five pounds.’

What fools! Sometimes she felt like denying them what they asked and making them beg. Every day at the same time the same faces. And every day the same cravings. Morning papers, evening papers, early, late editions, weeklies, cigarettes, chocolates.

Sandra chewed gum and tapped her red nails against the side of the till. If it was Sunday she could be at the open-air swimming pool. The Lido. In her new orange bikini. Sun-bathing and being ogled, on the tickly grass. Or at the coast with Dave Mitchell. Dave had a car, and he’d promised. But then — she let out an audible sigh which made Mrs Cooper, along the counter, turn her head — Dave didn’t have much else in his favour apart from his car. It would all lead up to the necessary routine of parking out of sight by some field on the way home. Service rendered; reward given. Things were all rather predictable with Dave Mitchell. Besides — the sea. All those rusty railings and pebbles.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.