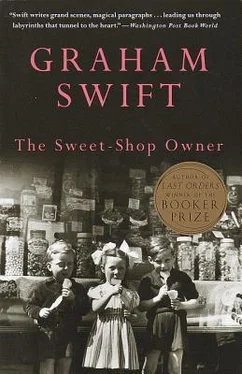

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Figures danced, silhouetted by flame. Composing, recomposing, round and round the fire. Yes, better dance, better rejoice. The war is won: that is something to rejoice over. But he had a lame leg (No, no, not a wound, he explained) and that was his excuse, and hers, for not dancing.

More fuel for the fire: don’t let it die. More fuel to make the sparks leap and the dancers whirl. Bring anything. Those old duck-boards from the shelter, those old out of date coupons, those letters stamped with the military franking from Cairo and Rome. Burn it all. Burn away the memories of five years, the ‘sacrifice’ and ‘endeavour’, the headlines, the photographs, the odour of barrack huts, the names of foreign battlefields, the 39,000 helmets, the 81,000 packs. But it wouldn’t burn. For, look, behind the flames, objects immune to fire, heroes of bronze and stone, too rigid and fixed ever to dance, and black names on marble, gold names on bronze, ‘undying memory’, ‘their name liveth’; and one of the names under the chestnut trees by the railings, on the white school memorial, where boys born after the war would be herded on Remembrance Day, was Harrison. No, it doesn’t burn, it doesn’t perish. Undying memories.

‘Irene!’

Who was that? It was Hancock. Stepping out of the shadows, in an Air Force uniform, with a beaker of beer in his hand, and a darkish, slightly curled moustache, grown since the war had started, to give the impression he was a pilot, not a ground officer.

‘Well I never. Come for the fun? Hello Willy old man.’

‘Hello Frank.’

‘Hello, helloh. Wangled some leave too?’

He rocked to and fro. Only his feet seemed to hold him to the ground, as if they were clamped with weights. One hand held his beer and the other was extended, palm forward, behind Irene’s back.

‘Fancy —’ He stood, open-mouthed, for a moment, as though embarrassed for something to say. ‘Well — there goes the war.’ He looked at the fire. He raised his beaker and brought his mouth to it by leaning his whole body.

‘Look —’ Irene said. She shifted forward.

‘Soon be out of this, eh Willy?’ Hancock tugged at his uniform. ‘Back to the shop?’ He winked, bobbed his head sideways, then stood, swaying, looking at the fire. Burning planks shifted in the blaze. He looked like a man in a train corridor watching scenes go by. ‘There it goes, there it goes. All over. Forgive and forget eh?’ When the train lurched his hand touched Irene’s waist.

‘Willy, let’s go.’

Dancers jostled by so they were hemmed in.

‘Hey, come on Irene!’

Hancock spread his arms and went springy like a tennis player.

‘Give us a dance.’ He held out a hand. ‘Don’t mind, do you, old man? Don’t dance — with that leg of yours — do you?’

Irene stepped back. For a moment Hancock waltzed gaily with the air.

‘You’ve got a nerve,’ Irene said.

‘Come on now, don’t be like that.’

‘You’ve had too much of that beer.’

Hancock looked at him. Strands of his moustache were wet and frothy. Irene seemed to look at something between them. She bit her lip. He didn’t understand any of this. They were standing in a row with people dancing round them, as in some game.

‘What’s the matter with you two?’ Hancock said. ‘The bloody war’s over you know.’

Better rejoice.

He said to Hancock: ‘It’s Irene’s father, he’s —’

‘No, that’s all right, Willy.’ Why was she scared?

‘One dance.’

Hancock looked spruce and forlorn in his uniform. He swung on his feet. Irene stood still. Her face was lit up like a statue’s. The piano played ‘Yours’.

‘All right,’ Hancock said. He shrugged ruefully, then looked swiftly at him as if he’d proved a point. Over the roof-tops searchlights were projecting great swaying Vs. ‘Just as you like.’

He finished the rest of his beer.

‘Be seeing you then.’

He made off through the swirl of dancers, palms extended, smiling now and then at other couples, his tall, agile body moving to the music, seeming to melt into the scene.

‘Let’s go, Willy.’

Across the common, figures were flitting in and out of the light of yet more fires. The searchlights weaved in the sky like diagrams. Why did they walk that way? Past the paddling pool, the children’s playground — the slide and swings had been salvaged in ’41, but it was the same playground — and up, not by the quickest route but by the path by the allotments, by the houses facing the sports ground. Because they’d walked that way before? When he worked at Ellis’s, in those lunch-times, when it was all yet to come. The same but not the same. There was an orchard of apple trees adjoining the back gardens. She had said once: ‘Did you know, that belongs to one of Father’s friends?’ But the fence was broken now, the rows of trees had not been pruned since the beginning of the war.

Victory, victory. But not for her. Along the path by the privet hedges and blossoming trees her face had tensed, as if to a vigil still to be maintained. Hancock? Was it Hancock? With his false fighter-pilot’s moustache. ‘Watch him,’ old Jones had said. But when he asked, ‘What was all that about?’ she only said, ‘That nonsense? Some day I’ll tell you.’

Later, up in the bedroom, she said suddenly, spreading her legs: ‘All right.’

Victory. But not for Mr Harrison, sinking slowly, surely in his coma, till he died in the small hours the following morning. ‘Peacefully,’ said the hospital. ‘Peace’, said the gravestone in St Stephen’s churchyard. That was Irene’s word: Peace. And had he found it, old Harrison, while his daughter stood, on the eve of victory, by his deathbed? For he’d leave the house to Mrs Harrison (she wouldn’t want it — a month after the funeral she’d go to live with Aunt Mad) and the flagging laundry to Paul (far away, in the Far East, where victory was yet to come); but the money, most of the money would be hers.

The searchlight Vs waved over the apple boughs. And what was that, from behind the fence? Voices in the grass.

II

14

As the clock showed half-past ten she opened the shop door. She stood for a moment in her white T-shirt, with buttons at the front, and blue skirt that barely hid her bottom, flipping back her brown hair, glancing at them with that look that said (in answer to everything): ‘So what?’

Well now we would see, thought Mrs Cooper, looking along the counter, whether he’d give her what she deserved or not.

Though she knew, of course, he wouldn’t. He indulged her, this brazen little seventeen-year-old. Pretended not to notice her idleness and impudence; treated her cheek almost with kindness, while her own long devotion he met merely with civility. ‘Thank you Mrs Cooper. That’s kind Mrs Cooper.’ ‘Mrs Cooper’ indeed! And he’d called that child ‘Sandra’ after only a week.

She watched him. He was counting out change but he had one eye on the girl.

‘Sorry I’m late.’ The girl grinned, unapologetically, and spoke in that slack, rubbery way which seemed to go with the chewing gum she continually worked and tugged around her mouth, making little sticky noises. ‘Got held up.’

She lifted the flap in the counter and passed through the gap, holding her stomach in and making small, sideways movements with her feet — an unnecessary performance, only designed to demonstrate her slimness.

‘You’ll get held up one of these days,’ Mrs Cooper said.

‘Yeh?’

Then she went into the stock room, slipping off her shoulder bag, to fetch her shop coat. Which she hardly needed, of course. Hers was pink, in contrast to Mrs Cooper’s dark blue. When she’d first got it she’d taken it home and raised the hem six inches. And once — it was a hot day three weeks ago, just like today — she’d stripped to her underwear to wear only the shop coat on top. Mrs Cooper had gone into the stock room and there she was in her knickers. It might have been Mr Chapman who’d walked in.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.