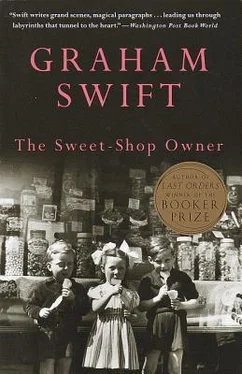

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

15

‘It will keep,’ she said, ‘It must keep.’

And so it had. Though along the High Street there were the little pits in walls where the fragments had struck, and here and there a window missing, and in Briar Street, not far from the infants’ school, sudden gaps of flattened rubble; so that you seemed to walk (but perhaps you always had) through a world in which holes might open, surfaces prove unsolid — like the paving-stones over which the children picked their way, returning to re-opened classrooms, dodging the fatal cracks. Yet it had kept. Intact. He had only to remove the boarding from the windows, retouch the paint-work, clear away the dust, and then — that was the most difficult part in that time of scarcity — refill the shelves with stock. And yet she knew all about that (it was almost as if she’d planned it), having worked all those months in the Food Office.

It must keep. Though things were scarce. Fewer coupons for clothes; units for bread; and those who said the ration books would go after a year or two were wrong. Prices rose. Half a crown for the cigarettes that in ’39 cost a shilling. And trailing round the streets of London in grey demob suits, trailing with them, like their former kit bags, the bundled stock of what they called their ‘experiences’, were thousands, looking for jobs and homes. There was much trading in ‘experiences’ but very little in homes. Little to buy, little to spend. And yet they’d said, Victory was ours, ours the reward, and some had spoken cheerily of the Fruits of Peace. And now they’d invented a new term to cloak the facts with an air of virtue: Austerity. But at least those children there, treading gingerly over the paving-stones, were assured of schooling, and of milk and orange juice. They were all numbered in a new system so they shouldn’t want. Smithy, who was childless, said that was a good thing. And you could count your blessings, with the news the servicemen brought home on Christmas leave from Germany: ‘They’re starving over there.’

He took down the ‘Closed’ notice, which five years had faded, from the door; sent off his forms to the Ministry and renewed his tobacco licence. Old Smithy, crossing the road, his barber’s jacket frayed and stained (you needed coupons for new ones), greeted his return. ‘So, come to mind your own store.’ There was a fondness in his eyes. His red and white barber’s pole twisted upward again, like a twirl of sea-side rock. And, see, along the damaged High Street they were returning again, like birds to their roosts, resuming their old ploys as if history could be circumvented and the war (what war?) veiled by the allurements of their windows: the thin assistant in Simpson’s replacing the tall flasks of coloured water high on their shelf; Hancock, in his office, scratching with a pencil that fraudulent moustache; and Powell — but they whispered, respectfully, about Powell. There were burn marks all down his back and his left arm — which is why he wore that grey, greasy cardigan and had acquired an ogreish expression. Yet he put out the vivid fruit, such as you could get then, doggedly enough.

Someone had to mind the store. Thrift was what victory cast up, after the cheering ebbed. And he saw what things would be needed, in this time of peace and parsi-mony. Sweets, cigarettes. Useless things.

Half-forgotten customers from before the war would shut the noise of the street behind them and linger, pick up old threads. The stories would be told — the bombs, the deeds of neighbours, the good or ill luck of husbands and sons — moments captured, sifted out of the actual long privations which did not seem to have ended with the war — stories which grew more unreal, more pensive, the nearer the teller got to the end of them, till he or she would stop, slip onto the counter the coupons and ask, as six years before, for a quarter of mints, a bag of rum and butters. ‘And you, Mr Chapman? What about your experiences?’

Experiences? But he had no experiences. Only the 81,000 packs and the 39,000 helmets.

In the evenings they counted the fiddly sweet coupons, threading them on strings at the dining table. And, more than once, he was tempted to sweep aside the carefully collected squares, like some card game that has proved inane.

‘We don’t have to make money,’ he said, losing count. ‘We have money — now — don’t we? So the shop —’

He eyed her over the green baize table-cloth.

‘Exactly,’ she said in a lucid tone. ‘Exactly. Don’t you see?’

She held her gaze on him. Her face, fretted already by her illnesses, was as frail as paper. It might crumble away completely.

And he knew: the shop was useless; its contents as flimsy as these interminable coupons they were counting. He was the shop-keeper.

The laughter leapt suddenly from her throat and skipped round the room. Then stopped, like something flung away and lost.

Would he hear her laugh again? Never so freely, or so wildly. But she didn’t break her bargain. She finished work at the Food Office. She went out on little necessary errands with shopping bag and ration book, or on more secret, private excursions, to bankers, brokers, dealers — though never (what were the traps awaiting her there?) to the High Street. But mostly she lurked, like some shy animal hidden in undergrowth, at Leigh Drive. At night he parted the leaves. Her body glimmered, received but did not yield. In the morning it was only a bedroom with pale green curtains. And yet she was preparing something. Down at the shop where she wouldn’t venture, he twisted up the little bags of sweets, rang the till, counted change, folded the newspapers (they spoke of the air lift to Berlin), and presented more expertly to his customers his shop-keeper’s camouflage. They didn’t realize (they only took their purchases and gave their money) how he’d perfected it; how it was only a disguise that faced them over the counter. Nor how she too sheltered behind that same disguise. For he saw how her preparations exposed her. She was less hidden, perhaps, by that undergrowth, than threatened by its rampancy, its sticky scents of growth; and only his own daily performance reassured her. He waited. In the evening he tended the garden while she watched from the window. Once, when he came home he found her unpacking cases of china. Pastel bowls and vases with white scrolls and tendrils and scenes from mythology on the side. ‘Wedgwood,’ she explained, without saying where she’d bought them. ‘Things like this will go up in value.’ And after examining them she packed them away again. ‘It wouldn’t do to break them.’

He felt afraid when she said, ‘I am going to have a child.’ Her own voice trembled slightly, though her eyes were bright with the knowledge of a promise fulfilled. As if she had proved a point, and now could be left alone.

That was November, 1948. The blue-rimmed tea cups had rattled on the kitchen table, the kettle hissed. For it was at breakfast she announced the news. So as to give no time, perhaps, for excessive reactions. She eyed the clock. She even led him, in her usual way, into the hall, taking his hat from the peg, ignoring his protest that for such a reason the shop might open late. Those unvarying habits had already formed — the keys, the briefcase by the umbrella stand, the dark grey suit for working — and that day was no exception. ‘Your hat Willy.’ Yet she let him kiss her and clasp her tight — was he afraid now she might slip away? — before she opened the front door.

A child. Something to rejoice over. Yet was it pure joy that made his steps seem light on that crisp November morning? Along Leigh Drive, down Brooke Close, over the common, past the swings and the paddling pool with its flotsam of dead leaves. As if the world slid heedlessly under his feet rather than submitted to his tread.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.