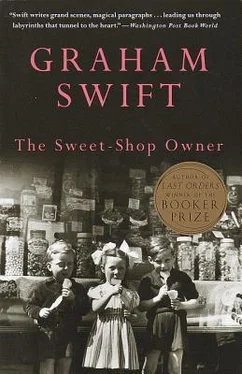

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She was bored. She’d give anything for something new. She’d go to the disco tonight, as she went every Friday, with Judy Bates and Linda Steele, looking for something new. But you could predict it all. Someone would start pawing her. Yes, because (unlike Judy Bates and Linda Steele) she had something to offer. And she’d calculate in return his assets and give, or not give (though, usually, she gave) the appropriate favour. But all this had become a kind of business. All predictable; nothing new. She’d try anything (even tempting an old man like Mr Chapman). But it seemed she’d already tried everything. Begun early. Behind the fence, near the allotments, at fifteen. Walking home with the blood between her legs.

She looked along the counter and caught Mrs Cooper’s sour gaze. Now there was something predictable. Still fuming with jealousy because Mr Chapman hadn’t been angry, had spoken softly when she was late, then helped her with the birthday cards. Mrs Cooper’s little game was obvious. ‘Yes Mr Chapman, let me Mr Chapman, I’ll do it.’ But Mr Chapman wasn’t interested. That was hardly surprising, was it? One day she’d have it out with that old bag. She’d say: ‘You’ll never have him!’ That would provide some excitement.

She served a man with cigarettes, who called her ‘darling’ and eyed her unbuttoned T-shirt as she leant forward with the change.

How hot it was getting! Across the road, up the street, they were sitting outside the Prince William, on the little wall by the pavement, glasses of beer in their hands, shirts off. The little half naked plastic dolls which hung in the Briar Street window looked as if they’d stripped for the heat. If only Mr Chapman would let her do the ice-cream. That was the best job in the hot weather. Lifting the black lid and putting your arm down into the cold, vapoury box. And you served mostly kids. Kids were best. They never seemed absurd, like these men and their eternal cigarettes.

But Mr Chapman was at the fridge. Relishing it. A small girl had come in asking for two cones, and she watched him plant the wafer cups in his left hand, push up the sleeve from his right, plunge down the metal scoop and with a stylish gesture top each cone and present them to the girl. The girl held out her money, smiling. Mr Chapman didn’t smile. He seldom did. Not actually. And yet somehow you felt he did. That’s why she liked him. He wasn’t obvious. How she’d hated at first that changeless expression, that everlasting blue or dark-grey suit, and how important it had become suddenly for her to change it, challenge it. Why not? An old man — it was something different. But he hadn’t reacted, no. He’d noticed, but his face had remained unmoved. She’d gone on trying to ruffle him; and it was only after a fortnight that she’d realized she did so because she wanted Mr Chapman to like her. She wanted to be liked by this unobvious, red-faced man of sixty.

And perhaps he did like her; for he’d given her, just now, twenty-five pounds, as a gift.

She watched him stooping, rearranging the contents of the fridge. His wife had died, not long before she’d started at the shop. What must she have been like?

‘Here!’ he suddenly said, producing two choc-ices from the fridge, tossing one, without further warning, to her and making to toss the other, like a juggler, across the full length of the shop to Mrs Cooper. ‘Cool off with these!’

‘Oh no Mr Chapman,’ Mrs Cooper protested, staying the throw. ‘Not while I’m busy at the counter.’ And she looked with virtue at Mr Chapman, and with malice at Sandra.

Sandra returned the stare. She’d never have him. One day she’d tell her.

Mr Chapman leant back on his stool by the fridge so that he looked along the counter. His face was heavy and weary. He was watching her eat her ice-cream. She bit off a mouthful. Twenty-five pounds, as a gift. Then he turned, suddenly, away. The thin coating of the choc-ice broke up beneath her fingers and slipped awkwardly. A piece fell on her skirt. She didn’t enjoy it.

‘Twenty Seniors, darling.’

She licked her fingers and dabbed at her skirt.

A new dress he’d said. Yes, she’d buy a new dress. She knew the very one. Deep red, with a black pattern. She’d seen it in Slik-Chiks. Yes, she’d go at lunch-time. It would suit her perfectly. Sexy, they’d say. She’d wear it to the disco tonight, get all the looks, and pretend all the time it was giving her pleasure.

She’d give anything for something new.

17

The stained-glass window in St Stephen’s church was bright with afternoon light. John the Baptist, in brown furs, and Christ, by a blue river Jordan. It shed little quivering patches of colour on the stone floor and the backs of the pews.

‘… except he be regenerate and born anew of water …’

He wore a pale grey suit with a white rose in the button-hole, and beside him he heard, in the silences of the service, her long, husky breaths. How accustomed would he get to that labouring sound?

Mrs Harrison was not there. Too ill, she said, replying to their dutiful invitation, to make the journey. But Aunt Madeleine was there, in a brown hat with black sequins, a conciliatory ambassador visiting under truce. ‘Will Paul be here?’ she said inquisitively, ‘I’d hoped Paul would be here.’ But no one heard from Paul. He didn’t write or phone. Aunt Madeleine said he was living in the North. Smithy stood beside Aunt Madeleine, in a sagging coat. For who else could he ask? Hancock? ‘Good God, no,’ she said, as they discussed arrangements. But it was difficult to deter him. ‘Hear you’re christening the little one,’ he’d said, casting his quick eye round the shop. And how could one say, ‘Don’t come’? So Smithy was there — he gave little looks of concern for Irene’s ragged breathing, and he was the one who opened doors for her, hastened to assist, as if the occasion were one of bereavement — and Hancock was there, sucking his teeth as the vicar spoke. Smithy brought his sister, Grace, thin, delicate and quiet; and Hancock brought — they’d never seen her before — the future Mrs Hancock.

‘Irene, Willy, meet my fiancée Helen.’

He gave Irene a little quick glance.

She was young, that Helen. No more than twenty-two. And Hancock, then, was thirty-six. She had blonde hair, waved like Lana Turner’s, and prominent breasts.

‘Let us pray,’ said the vicar.

Why St Stephen’s? ‘It’s the local church,’ she’d answered. ‘But they’ll never come,’ (and he meant, without saying, the marble plaque which glimmered, even now, on the far wall, beyond the pulpit; that, and the grave outside). ‘They’ll never come there.’ ‘It’s the best place — we will have it there.’ As if there were some logic. ‘We’d better put flowers on Father’s grave.’ ‘No,’ she said.

And so they stood, around the carved font, while the colours quivered on the floor, and the vicar spoke, who had spoken over Mr Harrison’s coffin.

‘I baptize thee in the name of the Father …’

(You didn’t cry, Dorry, or flail your arms when I dipped you quickly in the water.)

‘Congratulations Mrs Chapman.’ The vicar’s large and black-haired hand was extended. ‘And a very obliging little girl.’ Smithy stepped forward from the church porch holding his hat in one hand and dabbled a plump finger, as in a bowl, over the face wrapped in its white wool, then kissed Irene warily on the cheek. Hancock edged in, stood for a moment looking squarely at Irene, not regarding the baby between them, then laughed suddenly as if at his own joke, bent down and kissed the child. That rough moustache against that soft cheek.

There had been rain, but the sun gleamed on the pavement and on the wet laurels in the churchyard. The gravel made sucking noises as they walked over it. Helen giggled, holding her hat, picking her way round the puddles. Little orange spots of mud flecked her stockings. The wind was fresh, through the thin laburnums, making the sunlight clean and chill.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.