Patch has quite lost her glow. I don’t know how or why exactly, but she’s suddenly awfully pale of face and full of lethargy. Later that afternoon, when we’re all preparing to head off and see the starlings, she says she feels under the weather and asks to stay at home instead.

La Roux — he’s back wearing his balaclava again, which I presume must be a good sign — kindly offers to stay with her, but she shakes her head and mutters how she’d much rather be alone. At which point Poodle steps in and won’t take no for an answer.

She pulls off her coat and says she’s not particularly interested in seeing a pack of noisy, greasy starlings flying around anyway. So that is that , then.

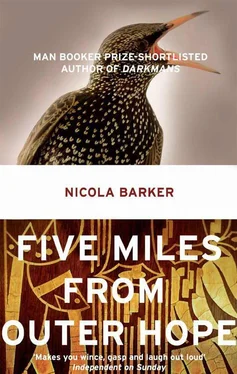

Much as I expected, the starlings are further away than Black Jack anticipated. We drive for fifty minutes, Feely, Big and me crammed on to the front seat, La Roux sitting alone in the open back, his balaclava off, his hair flying in the slipstream, and he’s sneaking the odd opportunity — when the impulse takes him — of hanging his head over the side and howling like an uptight, ill-trained, overexcitable puppy.

When we finally reach our location — a strangely flat, isolated and marshy area with extensive reedbeds concealing angry coots who yell from their hidden corners when we first arrive like irritable feathered fire alarms — the sky is grey and dusky. It’s also pretty damn empty .

Black Jack parks the car and we all clamber out. Nobody says anything. Silence. The odd coot shouts. Silence again. After fifteen minutes Big starts getting impatient. Are we in the right place? Is it the proper season?

‘Hang on a minute,’ La Roux says, spinning on the spot, ‘can’t you hear something?’

We all hold our breath and listen. At first I hear nothing. And then, a kind of windy noise, a swishing. Wings. Beating.

They’ve come . In their thousands. Like a hurricane. But silent, and ghostly. Not a stray tweet or an angry twitter among them. They arrive like a plague of feathers. Like a glossy, black whirlwind. A tornado of starlings, darting and spinning and turning and spiralling. Making shapes in the sky. Flying in formation. But madly. And randomly.

A million birds. One huge, great organism. One cloud. Then they divide. And join up again. They draw tigers in the air, and steam trains and pythons. They annex the sky in a single, stealthy, inky occupation of rapturous beak and shiny claw and piercing eye. Turning one way, then the other.

I glance at La Roux. He’s just to the right of me. His face is turned to the heavens, his mouth is open. He is crying .

When the sun has flown and the birds have set, La Roux takes a deep breath, then stands tall and turns and faces the assembled company.

‘I thought you should know,’ he says, clumsily pulling his balaclava back on again, ‘I’m so very grateful for all the things you’ve done for me, and I’m leaving in the morning.’

Then we drive home, darkly .

It’s a long night. Jack Henry spends the best part of it scurrying around inside my head catching cockroaches and devouring them ‘for the protein’. When he pauses for a moment, he tells me this story about how he once used his regulation Bible to make a club during a long run in solitary — he used water from the lavatory and constructed it out of papier maché — then when one of the guards popped his head in to check up on him, he bludgeoned him soundly with it. Cut him quite badly.

The man had been systematically tormenting him, he tells me, like you are, he says, like you are .

He seems to think this story is terribly funny for some reason. But when he laughs his stomach starts hurting. Bile . So he stops laughing and quietly starts hunting for bugs again.

I am awoken by Black Jack, banging heavily on the front door, and calling. It’s too early. Everything’s still dazy. I crawl out of bed to answer him. He’s breathless. He’s panting. He just got a call from the mainland, he says. Some people from the immigration service have asked for a quick lift over.

‘I’ve got to go,’ he tells me. ‘I delayed enough already.’

Big’s coming downstairs, rubbing his eyes, but I sprint up past him. Top floor, dark corridor, aquamarine door. I burst in.

La Roux is standing by the window. It is five-thirty a.m.

‘You’ve got to get out of here,’ I tell him, ‘the immigration people are coming. Maybe wait until they’re off the tractor and heading up here, then run around the back way and try crossing the water. It won’t be too deep. We’ll keep them busy in the meantime.’

He doesn’t say anything. He doesn’t say anything .

It’s bleak and bad and quiet and grey. It feels like we are dreaming.

The Immigration People, when they arrive, are the Immigration Person. One woman. Called Sandy. Skinny. Polite. Hails originally from Saffron Walden. Owns a pug, called Maudsley, she tells Big pleasantly over a quick cup of tea. A pedigree.

Believe it or not, she’s in no particular hurry.

He was never going to make it over. Can’t swim. Too risky. And the tide’s still strong. They pick him up, later, in a rowing boat. He’s wandering around aimlessly, waist-high in the water. The whole thing isn’t even scary or frightening. Just sad, and strange and a little embarrassing.

They tell us to pack the rest of his stuff together. So I go and I do it. The stupid white clay pipe, the cushion cover his mother made him, the picture of Spookie, his army pyjamas. His pony sweater.

On my way downstairs Big calls out my name and scurries up and — almost apologetically — shoves two spare crochet needles and two balls of wool into my hands. Then he scuttles off again.

Downstairs, in the kitchen, Patch is still lying face-down on the pine table, sobbing uncontrollably. Feely is sitting on his bean-bag, just next to her, like a clucky hen, staring up at the ceiling where the fan’s revolving.

I’m tearless, at this point, and resolving coldly to stay that way. But then something awful happens. On my way over to the mainland — the sea is gone, the sand is back, the beach is dry — Black Jack comes running down after me.

‘If you’re seeing him,’ he says, panting…

‘I’m not seeing him. I’m just dropping his stuff off at the Post Office. They’re picking it up later.

‘Well, anyway…’

He puts his hands into his pockets and pulls out three slightly battered packets of Iced Gems, and a fully illustrated colour book of British birdlife. ‘I thought he might like these,’ he shrugs, ‘as something small to remember me by.’

And that’s what finally gets me. The tears start welling and before I know it I’m bawling like a baby. And once I start, it’s difficult to think about stopping again. Because then, when I do, I know it will all truly be over. And he’ll be gone for ever. Back to South Africa. And military prison or wherever the hell they take people like him. And I know I’ll never see the skinny, self-centred, stupid, impolitic mother-fucker again.

On my miserable trudge back home to the hotel, I glance up and see Poodle sitting on the wall at the edge of the balcony, swinging her legs and staring blankly out to sea. I walk over and stand in front of her, seething. She smiles down at me, unfocused, almost dreamy. ‘I can see Outer Hope quite clearly from here,’ she tells me idly, ‘it’s such a clear day.’

‘Christabel,’ I snap back at her, my voice as tight as a skinny-rib-sweater, ‘I will never, never forgive you for the thing you did today.’

And I’m sixteen years old. And my nose is running. But I mean it. And I stand by it. I never will forgive her. Not ever.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу