‘Violence is no solution, Medve,’ he tells me (thereby violating every punitive penalty I am currently labouring under) ‘to this fine mess you’ve got us into.’

‘Wanna bet ?’ I bellow, and then I pause for a second. ‘Hang on. Who the hell do you think you are ? Oliver fucking Hardy ? The fine mess who got us into, anyway?’

He shakes his finger at me. ‘I think you probably heard me the first time, young lady.’ (Young lady ? What a dweeb. )

And do you think the fat brat is grateful for his muscular intervention? Is she heck ! Not a jot of it! ‘I can fight my own bloody battles,’ she yells, then marches off brazenly.

Is it just me, or has Poodle gone and soured everything ?

When supper is over (a monosyllabic occasion — La Roux and Feely staring, as if hypnotized, at Poodle’s sweet-scented and expensively encased bazookas, Poodle wincing at La Roux’s eating habits, Big inquiring constantly about Mo and Bob Ranger, Poodle evading him fairly ineffectually… ‘Yeah, they’re working very hard together…’, Patch and me still both sulking competitively: and guess who’s winning ?) Poodle comes downstairs to help me with the washing-up.

As soon as she thinks everyone is out of earshot, she throws in the towel and pulls out a chair. ‘Okay, Medve,’ she tells me, ‘we’ve got to get the South African out of here. And I mean yesterday.’

I turn and glare at her. ‘Why?’

‘It’s nothing personal, but his father’s sending Mo money and that’s the only reason she can currently afford to stay in America. The way I see it, we really need her home again.’

‘But I thought she was doing pretty well out there?’

Poodle growls exasperatedly. ‘She’s this fucking close, you moron,’ she flashes me an inch gap between her pretty fingers, ‘to leaving him.’

I blink. ‘Leaving who ?’

Her huge eyes widen. ‘Our poor father , stupid! Why the hell else would I decide to come back here? You honestly think I don’t have other places I’d much rather be?

‘And anyway ,’ she continues, ‘Big could get into serious trouble if he’s found guilty of giving shelter to an illegal immigrant. He’s the last person in the world who needs visa problems at the moment. Something like this could be a major black mark against him…’

I think she’s exaggerating, but before I can say anything I hear gentle steps on the stairway, so tip my head and shush her.

Five seconds later Big appears, and he’s beaming.

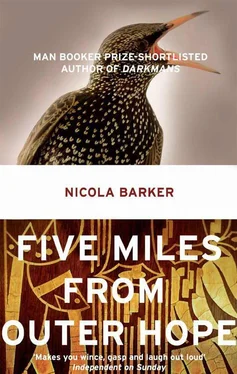

‘I’ve been speaking to Jack,’ he tells us, ‘and he was saying he’d had this great idea of taking us as a family to see a parliament of starlings. He’s borrowing a friend’s Land Rover tomorrow evening. It’s a very kind offer. Are the two of you interested?’

Poodle shrugs (she’s not much of a nature lover) and I nod.

‘Great. Then I’ll go and tell him.’ He prances off again.

‘I still can’t believe you got your breasts done,’ I snipe, returning to my washing-up duties (still in quite a tizzy about the South African dilemma). ‘How much did they cost you? I bet that ancient, leather-faced travel agent put his hand to his pocket.’

‘You know what?’ she oozes back at me. ‘I really can’t believe you’re still growing. Just a couple more months and that huge, fat head of yours will be scraping the ceiling.’

Oh God , how I hate her.

Big loves this girl so dearly that it is literally sickening to watch him around her. She makes him happy. He finds her funny. They go on special little walks together. They talk about the progress he’s making in the shrubberies and with his pathetic Yank crochet wall-hanging.

She confides in him about her surgery and how much having it done meant to her. And he tells her how he thinks it’s the person inside that really matters, so in his book she’s always been perfect anyway .

Can you believe all this clap-trap?

Yeah. So I won’t bother denying how hard it is having my beautiful older sister back home again. (I’m feeling like the outcast crow who never receives an invite to the fox’s cheese dinner.)

Suddenly, Poodle ’s the one Feely wants to read him a bedtime story. And Black Jack turns and stares after her when she totters past him in her expensive lizardskin heels and flying jacket (like she’s a gentle thief who’s stolen his eyes away). Even La Roux. Even he jumps on the bandwagon.

Over breakfast (on the morning after her arrival), he asks her courteously whether he can pour her more coffee (yes, we’re all drinking coffee now because this is Poodle’s brand-new beverage of preference). He’s stopped wearing his balaclava. His hair is oiled and shiny. His nails are clean. He’s even stopped smelling , temporarily.

It’s just too much disappointment for a single, ugly, gangly, envious girl giant to handle. So I spend the morning fishing, on my own. Thinking.

I mean, perhaps La Roux would be better off leaving. And perhaps Mo should come home again. And maybe Barge is a talented painter. And perhaps Big isn’t as small as he seems…

And maybe Feely should stop burping. And perhaps I really ought to start considering acting my age instead of my shoe-size (although the two — strictly speaking — are virtually identical).

Surprise surprise . The damn fish aren’t biting. I don’t catch a thing. But I do overhear an extraordinary conversation — on my return home for lunch — strolling through the foyer. Voices from the Ganges Room.

Poodle and La Roux. And she’s quietly and calmly asking him to go .

‘I don’t expect you to understand,’ she tells him, ‘but there are certain personal, family problems which only your leaving can rectify.’

La Roux doesn’t speak a word.

‘Big could get into trouble if the authorities find out you’re here. And the situation with Medve at the moment isn’t ideal, either. Anyhow,’ she wheedles in that awfully sweet but horribly direct way she’s perfected to an art form over the years, ‘I’m sure there must be people back in South Africa who are missing you terribly.’

‘The thing with Medve,’ La Roux intervenes, ‘just got a little out of hand…’

Poodle ignores him. ‘Big was telling me that you were a medic in the army,’ she slithers, ‘which I thought was wonderful .’

La Roux is silent again.

‘And the point is,’ she continues, ‘if you really didn’t want to go back for some reason, with the political situation as it is out there, I’m sure you could say you had moral objections to fighting in the war. Or that you were actively opposed to apartheid or something. I’m certain they’d buy it if you were sufficiently convincing…’

When La Roux next speaks, it is in a strange, dark voice. ‘I could never ,’ he whispers hoarsely, ‘I could never do that. It would be wrong. It would be cowardly. It would be cheap and weak and underhand .’

Oh dear. This is turning nasty. And I’m seriously thinking about sticking out my small chest and sticking in my big beak, when I suddenly hear footsteps, behind me, coming my way, so I turn on my tail and scarper, determining to corner Poodle later and have my bloody say.

After lunch — a sedate affair in the dining-room, with Poodle presiding — La Roux passes me on the stairs. We’re heading in opposite directions. ‘I have nowhere else to go,’ he whispers. Then he slowly continues descending, as if he hasn’t even spoken.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу