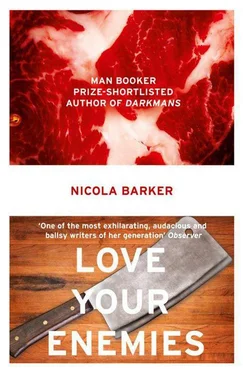

Nicola Barker

Love Your Enemies

Layla Carter was just about as happy as it was possible for a sixteen-year-old North London girl to be who possessed a nose at least two centimetres longer than any nose among those of her contemporaries. As with all subjects of a sensitive nature, the length of Layla’s nose was an issue of great topicality and contention. Common clichés such as ‘Don’t be nosy’ or ‘You’re getting up my nose’, even everyday phrases like ‘Who knows?’ — especially when uttered by an errant younger brother with a meaningful glance at the relevant part of Layla’s physiognomy — would cause an atmosphere of hysterical teenage uproar in the Carters’ semi-detached in the leafy suburbs of Winchmore Hill.

Layla sensed that the source of her problem was genetic, but neither of her parents, Rose and Larry Carter, possessed noses of any note. Her three siblings were blessed with lovely, truffling pink snouts with snub ends and tiny nostrils. They had nothing to complain about.

Her nose had always been big. On family occasions like Christmas or Easter when her grandparents and great aunts descended on the Carter household for a roast lunch and a glass of Safeways own-brand port, the family photo albums would be dragged out of the cabinet under the television and all tied by blood and name would pore over them and sigh.

No one sighed louder than Layla. Her odyssey of agony and self-consciousness began with her christening snaps and continued well after the visitors had gone home, the washing-up had been done and the living-room carpet hoovered.

As far as she could tell, her nose had always been disproportionate. She had often had recourse to see other people’s christening photographs, and in none of them that she could remember had so many profile shots been taken to so much ill effect. Her nose emerged like a shark’s fin from between the delicate folds of her fine, pearly-white shawl, and the sight of it cut into her stomach like a blade.

She struggled to remember a time when the size of her nose hadn’t been a full-time preoccupation. As a young child in her first weeks at school, after a particularly violent spate of playground jousting — little boys shouting ‘big nose’ at her for a period in excess of fifteen minutes — her class teacher had bustled her, howling, into the staff-room and had dried her eyes, saying softly, ‘When you grow older you’ll study the Romans. They were the people who built all the best, long, straight roads in Britain, many, many years ago. Now just you guess what all of the Romans had in common? They all had fine aquiline noses. Long, straight, proud noses like yours. One day you’ll learn to be proud of your nose too. You’ll learn that all the best people have strong, bold, expressive faces and strong, proud, dignified noses.’ She offered Layla a tissue and said, ‘Now go on, blow.’ Layla pushed her face forward and then felt a pang of intense misery as her nose poked a hole through the centre of the tissue; like a dog jumping through a paper hoop. Nothing could console her.

People are so cruel, children are so cruel. In the school playground as she grew older, worse humiliations were in store. Her nose became her central signifier. Whenever her best friend Marcy was deputized to approach a handsome young buck for whom Layla had developed a girlish passion, she would always see him turn to Marcy with a frown and say, ‘Layla? Who’s she?’

By way of explanation Marcy would invariably point her out as she stood skulking in the corner of the playground closest to the girls’ toilets and say, ‘That’s her there. You know, the one with the big nose.’

Marcy always apologized for her indiscretions. She was a sympathetic girl, but she came from a big family where sensitivity and tact often had to be abandoned in the arena of attention-grabbing. She would say to Layla, ‘I’d much rather have a big nose than no nose at all.’

Neither of them had ever seen anyone without a nose before, but as the years dragged by Layla regularly stood in front of her bedroom mirror with her hand covering this offending part of her face in an attempt to perceive herself, and her other features, without its overwhelming presence. The result was often quite gratifying. Whenever she tried moaning to her mother, Rose would say, ‘Just be grateful for what you have got. You’ve got pretty blue eyes and lovely soft, brown, curly hair. You’ve got a good figure too. Be grateful. Try not to be so negative.’ In return, Layla would grimace and shout, ‘God! It’s bad enough having a nose like Mount Everest — I’d hardly tolerate being fat as well. I have to make the best of myself, but that doesn’t make things any better. In some ways that makes things worse. If I was truly ugly, what would I care if I had a big nose?’

She wished she could chop it off. When she was twelve, a short burst of appointments with the school therapist brought more light to this preoccupation. The therapist told Rose and Larry that Layla’s regular association in her conscious and unconscious mind with chopping and removal implied a rather unusual and boyish adherence to what is commonly called the castration complex. He said, ‘Layla wants to be a man. She wants to rival her father, Larry, for Rose’s love and attention. Unfortunately she has no penis. This makes the penis a hate object. She wants to castrate Larry’s penis because she is jealous of it. She feels guilty about her aggressive impulses towards Larry and so turns these feelings of violence on to herself. To Layla, her nose is a penis. Her hatred of her nose is symbolic of her hatred of her own sexuality. When she comes to terms with that, she’ll be a happier and more complete person.’

After their appointment the Carters took Layla for a hamburger at the McDonald’s in Enfield’s town centre as a treat. She sipped her milkshake and frowned. She said, ‘What difference does all this make to me? Talking won’t change the size of my nose, will it? Why does everyone have to pretend that my nose isn’t the problem but that I am? It’s as if everyone who wants to help me is determined to believe that my nose isn’t all that big at all. But it is. It is!’

She had made her point. The family paid no heed to the therapist’s recommendations. Except Larry, who took to locking the bedroom and the bathroom doors whenever he happened to undress; especially when shaving. He must have felt guilty about something.

By the time that she was fifteen, Layla knew everything conceivable about dealing with an outsize nose. She knew how to react when boys got on to the school bus in the afternoons and laughed at her and gesticulated, she knew how to comb and style her hair in a way that helped to accentuate her better features as opposed to her worse, she knew how to avoid having her photograph taken on family occasions (on holiday and at home), she knew how to spend hours every morning with a make-up brush and facial foundation, shading the sides of her nose and lightening its centre in a way she’d seen depicted in hundreds of teenage girls’ magazines. Most of all she knew how to focus on this one, single thing. She made herself into a nose on legs.

She could not read a magazine without studying the nose of every model on its waxy, paper pages. If a model had a slightly larger nose than usual she would tear out the picture and put it into a scrapbook or stuff it in the drawer of her desk. At night she would list in her mind successful people who had big noses. She counted them like sheep in her pre-dream state; Chryssie Hynde, Margaret Thatcher, Barbra Streisand, Bette Midler, Dustin Hoffman, Rowan Atkinson, Cher. She thought about Cher quite a bit, because Cher had had her nose fixed.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу