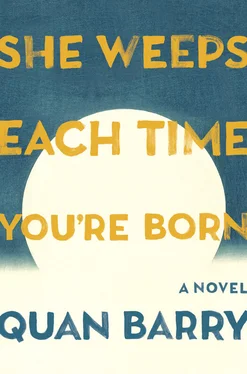

Quan Barry

She Weeps Each Time You're Born

And then She saw them — burn! burn!

and simply the water was made as glass.

And She is the way when there is no way.

She weeps each time you’re born.

Glossary of Foreign Terms

Bà—grandmother

Ba — father

Em — a form of direct address used for children

Ong — grandfather

non la —a conical straw hat

ao dai —a traditional Vietnamese dress

She Weeps Each Time You're Born

THE SAMPAN RIDE BACK DOWN THE SWALLOW BIRD RIVER IS uneventful, everywhere the dragonflies floating fat and red in the late-afternoon sun. The same oarswoman who rowed us out to the Mountain of the Fragrant Traces now methodically bears us away. We’re all tired — even crazy Hung, his sunglasses firmly in place, seems to slump in his seat, a cigarette burning down between his fingers. The water is calm, the landscape lush and meditative, and when it comes time to leave the boat, the three of us remain sitting for a moment as if stunned, hardly believing the day is almost over.

On the back of Than’s motorcycle I pass the same sights we saw on the way out. Everything looks familiar, like scenes from a previous life — the harvest still drying in the middle of the road, the people doubled over in the paddies in the fading light. I have spent the last week touring around the northern countryside with Hung and Than as my guides; after only a few days I trust them completely. Then Hung pulls up alongside one more time, his motorcycle splashed with mud. He looks at Than and makes a hand signal before taking off up the road. There one thing more, Than shouts over the roar of the engine. Because you are lucky, Amy Quan, yells Than, Hung thinks maybe she see us.

Ten minutes later we pull up out front. The simple wooden house is a perfect square, the boards splintery and gray, a ragged cloth hanging in the window in lieu of glass. In the yard, a handful of chickens and pigs cluster in the shade of a tree, this late in the day the heat still invasive, all smothering. I can tell something is different this time, something in the way Hung and Than keep glancing over their shoulders. Neither of them has lit up a cigarette. This not the house, whispers Than, we just park here. Up close a black crack weaves across one of his front teeth like a piece of string waiting to unravel. Than nods to Hung. Go with him, he says. For a moment he seems like he’s about to say more, but he leaves it at that.

For the first time all day, Hung has taken off his sunglasses. Pale rings circle his eyes where the sun rarely touches his skin. Already there is a newfound earnestness in his demeanor. Hung the merry prankster. Hung who pretended to try to flip the sampan while we were gliding down the Swallow Bird River. I had caught a glimpse of this other Hung earlier at the Perfume Pagoda. The way he didn’t know which of the two entrances to walk through, the Gate to Heaven or the Gate to Hell, and when he followed Than through the Gate to Heaven, how even with his sunglasses on, I could see the relief flooding his face.

The house is a quarter mile down the road. There are only four other houses in the area, each one also small and wooden, a rusty sheet of corrugated tin on the roof. Firelight flickers in the windows. As we walk, Hung keeps taking deep breaths in through his mouth. He moves with an air of quiet contemplation, head bowed as he leads me to this place he thinks I of all people need to be. In the silence his eyes glisten. Despite his constant clowning, at times I have sensed a deep sadness in him, as if his frequent jesting is keeping an inner darkness at bay. Beside me he treads like a man without hope. If I didn’t know any better, I might think he is afraid of where we are going.

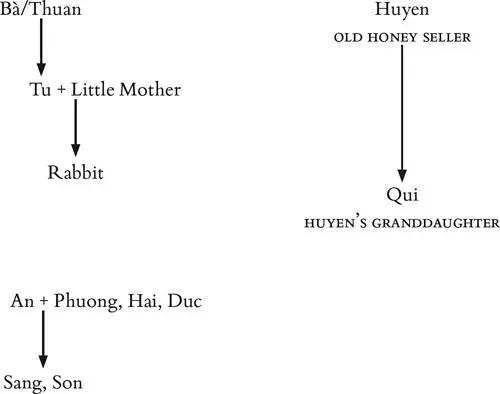

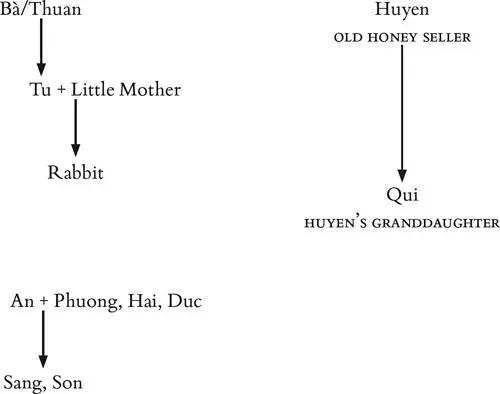

The moon teeters low on the horizon. I can hear crickets and frogs starting to call. Than and me, our families come from Saigon, Hung says in a low voice. The government doesn’t trust southern people. No Hanoi business will hire us. So we’re guides. He looks at me and I nod. Her name’s Thỏ, he says. Rabbit. For Vietnam she gives up everything. His voice is barely a whisper as if he is really talking to himself. She will stay until every little one is heard. The northern and southern dead. Hung takes one more deep breath. He puts his hand on the gate. Now she’s in house arrest, he whispers. No one is allowed, but out here … He nods around at the isolation of the landscape. A seedpod from a nearby tamarind falls on the metal roof, the clang echoing like a bell.

The gate swings open on its rusty hinges, the sound almost painful to the ears. Silently we enter the yard in the shadows as the full moon rises behind us with its long grayed face, and then someone opens the door and waves at the ground and I hear a voice which doesn’t sound fully human calling xin chao, xin chao . Welcome. Welcome.

Later, back outside, the moon burns bright, the lights of Hanoi visible in the distance. Than turns the motorcycle off the rural road and onto the highway where we wait our turn to pay a toll. Around both wrists he wears a bracelet of prayer beads, each one inscribed with a tiny image of Quan Am, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, who Than says keeps him in Her sight as he wanders far from home. Now the street will turn to asphalt, the way smooth and clear. As we wait, I notice a young boy walking barefoot by the side of the road, a dirty piece of cloth wrapped around his waist. In the years to come I will make three more trips to Vietnam, the country of my birth, piecing together the story of Rabbit, of how she was born in the dirt and the sorrows to follow. I have spent the past six weeks touring Vietnam, this place where I was born in the same year as her, our lives diametrically opposite. I have seen everything the guide books speak of — Reunification Palace, the endless rubber plantations, tunnels running hundreds of miles under the earth. This is not a story of what is missing. Some things just have yet to be found.

As we wait in line to pay the toll, I watch the young boy walking barefoot along the shoulder. The highway before us is a long treeless strip of concrete miles from anywhere. Even now as I write this a decade later I wonder where the boy came from. I can still see him smiling to himself, holding something close to his chest that wriggles and flashes in the growing moonlight, the boy’s ribs like a lattice. I stare harder. Slowly the cars inch forward, the drivers impatient, the bills ready in their hands, Than revving his engine. Then I see it — the boy is holding a live fish, the thing more than a foot long, his right hand lovingly stroking its pale iridescent belly, and he is walking down the side of a highway at night in Vietnam as though he has all the time in the world.

On this we do not agree. Some of us say she was made manifest in a muddy ditch on the way to the pineapple plantation. Others say it happened hunkered down in a piggery, the little ones with their wet snouts full of wonder at the strange bristleless being wriggling among them for milk. Either way we bow to you. Believe us when we say life is a wheel. There was no beginning. There is no end. But we will tell you the story as she believes it occurred under the full rabbit moon six feet below ground in a wooden box, her mother’s hands cold as ice, overhead the bats of good fortune flitting through the dark .

Читать дальше