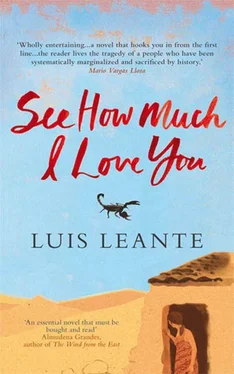

Luis Leante

See How Much I Love You

When I’m on foreign land,

And recognise your colours,

And think of your exploits,

See how much I love you…

Little flag you’re red,

Little flag you’re golden

Full of blood and full of riches

At the bottom of your soul.

Las Corsarias, Music and lyrics by Franciso Alonso

SHE SLEEPS THROUGH THE MORNING, INTO THE EVENING, she sleeps through most of the day. Then she stays awake for the best part of the night: it is an intermittent wakefulness, with moments of brief lucidity and others of delirium or abandon; she often faints. She is like this, day in, day out, for weeks. She is completely oblivious to the passing of time. Whenever she is able to stay conscious, she tries to open her eyes, but soon falls back into the depths of sleep, a heavy sleep from which she finds it hard to come round.

For days now she’s been hearing voices in her moments of lucidity. They sound distant, as though they were coming from another room or the deepest end of her sleep. Only occasionally does she hear them near her, by her side. She cannot say for sure, but it sounds as if the unknown voices are speaking in Arabic. They talk in whispers. She doesn’t understand a thing they’re saying, but the sound of those voices, far from being disquieting, is comforting to her.

She finds it hard, very hard to think straight. When she makes an effort to understand where she is, she feels a great tiredness, and very soon falls back into her dreaded sleep. She struggles to stay awake, because hallucinations torment her. Over and over she is seized by the same image: the nightmare of the scorpion. Even when she’s awake she fears opening her eyes in case the arachnid has survived the dream. But however hard she tries, her eyelids remain sealed.

The first time she manages to open her eyes she cannot see a thing. The dazzling light of the room blinds her, as if she’d been in a dungeon all along. Her eyelids grow heavy and give in. But now, for the first time, she is able to tell reality from reverie.

‘Skifak? Esmak ?’ says somebody, very softly.

It is a soft, woman’s voice. Although she doesn’t understand the words, the tone is clearly friendly. She recognises the voice as the one she’s been hearing over the past few days or weeks, sometimes very close to her ear and at others, in the distance, as if coming from another room. Yet she has no strength to reply.

Still conscious, she cannot rid her mind of the image of the scorpion, which is more troubling than an ordinary nightmare. She can even feel its carapace and legs creeping up her calf. She tries to convince herself that it is not really happening. She tries to move, but has no strength. In reality the sting was short and quick, like the prick of a needle. If it had not been for that woman’s shouts of warning; ‘ Señorita, señorita , careful, señorita !’ she wouldn’t have seen it at all. But she turned to look as she was slipping her arm into the burnous,1 saw the scorpion hanging from the lining and knew that it had stung her. She had to cover her mouth so as not to shout, and was distressed by the voices of the women who, sitting or crouching down, stared at her in horror.

She’s never sure what posture she fell asleep in. Sometimes she wakes lying face up and sometimes face down. And so she realises that someone must be moving her, no doubt so that she won’t get bed sores. The first thing she sees are the shadows in the ceiling where the plaster is coming off. Dim light comes in through a small window situated high up on the wall. She doesn’t know whether it’s dawn or dusk. No noises can be heard that might indicate life outside the room. Against the opposite wall, she discovers an old rusty bed. Her heart jumps when she realises it is a hospital bed. There’s no mattress on it. The bedsprings openly display signs of neglect. Between the two beds is a metal night table, which must once have been white but is now tainted by decay. For the first time she feels cold. She strains to hear a familiar sound. No use; there’s nothing. She tries to speak, to ask for help, but cannot utter a word. She spends what little strength she has trying to attract someone, anyone’s attention. Suddenly the door opens and a woman she has never seen before comes in. She realises that the newcomer is either a doctor or a nurse. A brightly coloured melfa2 covers her from head to toe, and over it the woman wears a green gown with all the buttons done up. On seeing that she is awake, the nurse flails her arms in surprise, but takes a moment to react.

‘ Skifak? Skifak ?’ the nurse blurts out.

Although she doesn’t understand the words, she assumes she’s being asked how she’s feeling. But she cannot move a single throat muscle to reply. She follows the nurse with her eyes, trying to recognise her features underneath the melfa covering her hair. The nurse leaves the room calling out for help, and presently returns with a man and another woman. They talk between themselves hurriedly, though without raising their voices. All three are wearing medical gowns, the women over the top of their melfas . The man takes the patient’s wrist and feels her pulse. He asks the women to keep quiet. He lifts her eyelids and meticulously examines her pupils. He listens to her chest with a stethoscope. The metal feels flaming hot against her chest. The doctor’s face shows he is perplexed. The nurse, who had left the room a moment ago, returns with a glass of water. The two women help her to sit up and drink. Her lips barely open. Water runs over the corners of her mouth and down her neck. When they lay her back down, they see her eyes turn white and she falls fast asleep, just as she has been for nearly four weeks now, since the day she was brought in and everyone thought she was going to die.

‘ Señorita, señorita , careful, señorita !’ She’s heard the voice in her dreams so many times that by now it is utterly familiar. ‘Careful, señorita !’ But at first she didn’t know what all the shouting was about — until she saw the scorpion hanging from the lining of the burnous. At once she knew she’d been stung. The shouting spread amongst the women, and they covered their faces and uttered laments as if a terrible tragedy had taken place. ‘ Allez, allez ,’ she shouted for her part, trying to make herself heard above the screams. ‘Come with me, don’t just sit there. Allez .’ But the women either couldn’t, or were refusing to understand her. They covered their faces with neck scarves and would not stop moaning. In the end she lost patience and started insulting them. ‘You’re a bunch of ignorant idiots. If we don’t get out of here they’ll rape us. It’s outrageous that you let them treat you like this. This is worse than slavery, this is… this…’

Discouraged, she fell silent, because she saw that they did not understand her. At least they weren’t shouting any more. She stood still and quiet in front of the twenty women who, frozen with fear, avoided her gaze. She waited for a reaction, but no-one took a step forward. On the contrary, they huddled together like pigeons at the back of the cell, seeking comfort in each other, praying and covering their faces. For the first time she thought about the scorpion. She knew that of the one thousand five hundred living species only twenty-five are poisonous. She quickly swept the thought aside.

There was no time to lose. Now it seemed certain that if no one had responded to the shouts it was because they’d been left alone, unguarded. She finished wrapping the

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)