‘Nothing much, I guess: I’ll watch the ski jumping and the waltz competition on TV, and get fat with no regrets.’

‘I was thinking you could come round for dinner. Matías has brought some of that cod you like so much from his hometown.’

‘Cod on New Year’s Day? What about turkey and rice? The tradition that made our cuisine so great?’

‘You couldn’t be more old-fashioned!’

The door opened and an intern walked in, wearing gloves and surgical mask at a crooked angle.

‘Montse, we need you.’

Doctor Cambra stood up and left her coffee on the table without having even sipped from it.

‘All right,’ she said before leaving, ‘tomorrow at yours. If you like I’ll tape the ski jumps.’

‘No thanks. I’ll watch them live. My son loves them.’

Between eleven and twelve-thirty, the Casualty Ward was particularly quiet. A few staff members went over to the cafeteria for a bite to eat; others preferred to share home dishes in the staff room. It was the worst period of the night for Doctor Cambra.

The girl’s parents appeared a little before the clock struck twelve, harrowed by their daughter’s accident. Doctor Montserrat Cambra took special care of them. Against hospital regulations, she even allowed them to go in and see their daughter for a few minutes.

‘She’s been very lucky,’ she told the parents, who wept in front of the badly injured girl. ‘Don’t be scared by the intubation and all the bandages. It’s only saline solution and pain killers. Her head is absolutely fine. She’s broken a collarbone and a tibia. The worst thing, though, are the injuries to her hand, but with surgery and proper physical therapy there’ll be no serious consequences.’

The mother burst into tears as soon as she finished the report.

‘But she’s fine, trust me. In a month she’ll be nearly back to normal.’

Doctor Cambra was doing her best to lift the parents’ spirits, but she herself was sinking deeper into the terrifying hole. As soon as she could, she excused herself and walked away. Back in the staff room, the doctors and nurses on duty were toasting the new year in with plastic cups and making confetti out of old spreadsheets. The new century had crept in. A doctor from traumatology kissed her and wished her a happy new year. He was nervous and particularly clumsy, and nearly spilled coffee all over her.

‘You haven’t called me all week,’ he said, trying not to sound reproachful.

‘I didn’t get a chance, Pere, honestly. I had a million things to do here.’

‘Well, if that’s the only reason…’

‘Of course it is. You’re a great guy, honestly.’

The doctor walked off, wary of prying eyes. Belén approached her friend from behind and whispered in her ear:

‘You haven’t called me all week, Montse.’

She blushed so much she thought everyone would see.

‘You’re a great guy, honestly,’ continued the anaesthetist, imitating Montse’s affected tone.

‘Will you shut up! Don’t you realise he’s listening?’

‘Who, Pere? He’s deaf in one ear, as I’m sure you know. I myself anaesthetised him for the operation.’

‘You’re a witch.’

‘And you’re a bit jumpy today. Didn’t you know Pere is the hospital’s most eligible bachelor?’

‘And did you know that the most eligible bachelor falls short where it matters?’

Belén covered her mouth in a exaggerated gesture of surprise.

‘Really!’

‘You heard me.’

‘Well, nobody’s perfect, darling.’

The rest of the shift went as everyone expected: people coming and going up and down corridors, opening and closing doors, pushing gurneys in and out of rooms. It would have ended like any other shift Doctor Cambra had worked in her long career, had it not been for a series of coincidences that took place in the first hours of the new century.

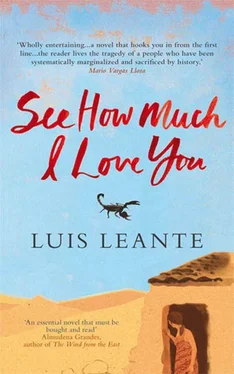

At three-fifteen in the morning, an ambulance from the Casualty Ward of the Hospital de Barcelona picked up a twenty-five-year-old Arabic pregnant woman, who had been run over at the airport. First coincidence: the ambulance, which was speeding at over ninety kilometres an hour along Gran Via de Les Cort Catalanes, encountered a traffic jam when it reached Carrer de Badal; three cars had crashed and were on fire. That was the shortest way to the Hospital de Barcelona, but it was now impossible to pass through the fire engines and police cars gathering in the area, and so the driver carried on along the main road looking for the nearest hospital. Second coincidence: when the driver radioed the Hospital Clinic i Provincial, who told him they were expecting four people with severe burns, and advised him to proceed to his initial destination. Third coincidence: when the ambulance was about to take a turn at Plaça de les Glóries Catalanes in order to go back up Diagonal towards the Hospital, the driver made a mistake while turning a sharp corner and ended up on the wrong road. Fourth coincidence: as the driver was trying to orientate himself, he chanced on the main façade of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i de Sant Pau, and before he knew where he was, he saw the red lights of the Casualty Ward. The moment the stretcher crossed the threshold, the woman lost all her vitals, and presently a nurse realised she was dead. Fifth coincidence: just when doctor Cambra was seeing an old man who’d been admitted with an asthma attack, an orderly and an intern left the gurney with the body of the pregnant woman next to her. A certain something made Doctor Cambra take notice of that woman: perhaps the beauty of her features, the colourful piece of cloth wrapped around her, or her advanced pregnancy. Though no one asked her to, Doctor Cambra took her pulse at the throat; then she lifted her eyelids and found the pupils dilated and non-reactive, which confirmed that the woman was dead. Her features were placid, as if she’d died with a smile on her face. At reception, meanwhile, there was a bit of a commotion, and a discussion started between the administrative and ambulance staff. Doctor Cambra, without really meaning to, learned all the details. The victim’s husband, who had not been allowed on the ambulance, had taken a taxi to the Hospital de Barcelona, where he was no doubt asking about his wife at that very moment. Also, all the woman’s papers, passport and documents were in Arabic, so no one knew who to contact about the death. Doctor Cambra stepped in and tried to make some sense of it all.

‘Call the other casualty department, explain what’s happened, and tell them to send the husband over as soon as he gets there.’

They looked at each other, with all the tiredness one feels at half three in the morning.

‘And don’t mention she’s dead.’

Doctor Cambra looked again at the woman’s disquietingly peaceful face. In other circumstances, it would have looked contented. As two assistants put what the woman carried in her pockets and purse on a little table, Montse picked up a form and examined her injuries, trying to figure out how the accident had happened. In the form she entered the estimated age of the victim: twenty-five. It made her shiver. For a moment she saw herself at that age, walking arm in arm with Alberto, or dancing with him at Caldaqués, pregnant and envied by the resentful girls from Barcelona also on holiday at the seaside. Then, another coincidence, she leaned on the small table to write more comfortably, and the woman’s personal effects fell off. This wouldn’t have mattered much in itself if, on bending down to pick them up, Montserat Cambra hadn’t seen three or four photographs, one of which strongly attracted her attention.

It was in black and white. Two men appeared in the centre, shown from the knees up. They were the same height. Both smiled at the camera, as though they were the happiest people in the world. Behind them was the front of a Land Rover with a spare wheel on the bonnet. Further back there were countless Bedouin tents, lined up all the way to the horizon. Among the tents there were groups of goats lying on the ground. The two men had their arms around each other’s shoulders, in a gesture of comradeship. They were very close to one another, their faces nearly touching. One of them had Arab features: he was wearing military clothes and making the V sign with his hand. The other was clearly a Westerner, in spite of his attire. He was dressed like Laurence of Arabia, with a long white tunic and a dark turban, undone and hanging loose over his shoulders. He had very short hair and an old-fashioned moustache. In his right hand he was holding a gun in a very cinematographic gesture. What most attracted the viewer’s attention were the men’s smiles.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)