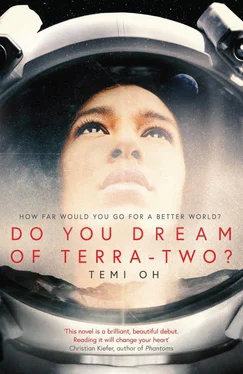

Temi Oh

DO YOU DREAM OF TERRA-TWO?

This book is dedicated to my Grandmother

and my Grand Mother

And – lovingly, loyally, gratefully –

to Benedict Douglas-Scott

Senior Astronauts

Commander Solomon Sheppard – Commander and Pilot

Igor Bovarin – Flight Engineer

Dr Margret ‘Maggie’ Millburrow – Flight Surgeon

Dr Cai Tsang – Botanist and Hydroponics Expert

The Beta

Harrison ‘Harry’ Bellgrave – Pilot/Commander-in-Training

Poppy Lane – Head of Communications/In-flight Correspondent

Juno Juma – Trainee Medical Officer

Astrid Juma – Junior Astrobiologist

Eliot Liston – Junior Flight Engineer

Ara Shah – Junior Botanist

Other

Jesse Solloway – First Alternate Beta

Dr Friederike ‘Fae’ Golinsky – Lead medical officer

‘We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for the journey and waved goodbye and “slipped the surly bonds of Earth” to “touch the face of God”.’

Peggy Noonan for Ronald Reagan

It is just like Earth, Terra-Two. It has turned in silence for millennia on the same spiralled arm of the galaxy. It is enveloped in temperate air, oxygen, nitrogen, noble gases, dark oceans licking empty shores. It’s luxuriant with life. Trees burst from the dirt. Electric-blue fish slalom through coral reefs and the wind is heavy with spores that germinate in shadows. Wild, everything, the land and the flowers.

But there is nobody on it.

When we ask ‘Why?’, they say ‘Because we haven’t sent anyone yet’, although really they’re saying, ‘Because there is nobody else out there. Not on any of the worlds.’ We are the only thinking heads in the universe.

We were taught that, for a while, the universe existed and not one person knew. Stars exploded, nebulae collapsed, atoms crashed together and formed planets, then quiet oceans where single-celled organisms swallowed light and learned to flourish, then more complex life, plants, then creatures dragged their heavy bodies from primordial seas, shook off fins, feathers, opened eyes, but not one of them was capable of awe. Not one of them wondered at the lines on their palm and asked ‘How?’, or shouted at the stars as we did – for a time – searching for fellow travellers.

We know now that consciousness is rare. It’s wretched and magnificent and lonely. It allowed humans to conquer the empty moon, the mountains of Mars, then Europa, Callisto and the rings of Saturn.

They planned the journey to Terra-Two and when they named the six of us how could we say no? We were young. They had hauled us from obscurity to hurl us at the stars, and we were dizzied by shallow fantasies of being the first, of leaving our footprints on the land, pushing our flag down into the dirt, giving it a name, dividing and taming it.

Did we forget about the darkness? Did we shrug off the loneliness and the labour? Did we regret? Of course we did.

We have been told that Terra-Two is waiting for us, and perhaps it still is. Perhaps the sand has washed up on the shores in quiet anticipation of the day we set our soles dancing across it.

Some nights we ask ourselves why we chose to leave everything behind. We used to think we had many reasons, but – really – there is only one.

2004–2012

HE HAD DEVELOPED THE habit of tapping his thumb against the tips of his fingers. The index first, three, four, five again and again, perfected to a quick, quiet art. He had read online that it was a test of neurological agility. When the neurons in his brain began to pop out like lightbulbs he would no longer be able to perform this minor feat. Nor would he be able to roll a two pence coin over his knuckles forward and then back in one fluid motion so the penny slid across his lissom hands – another skill mastered over years of staring out the window during tutorials, watching blossoms fall and thinking about death.

Jesse thought about death a lot, in the beginning, with the same detached curiosity roused by the sight of a car accident. He had been told that he would die before he turned twenty.

During a trip to Indonesia, a medicine man had taken his sister’s hand and told her she would fall sick but not leave this Earth, and then stared down at the lines of Jesse’s own palm and said that in nine years he would .

It was only after his sister’s preternatural recovery from cerebral malaria that Jesse began to give some thought to how he might die. He’d been eleven, then. Young and relatively healthy, it was unlikely to be an accident of genetics or something insidious and tragic like leukaemia. He hoped that, when death came, it would be quick as a knife. Something as dramatic as a car accident or gunshot wound seemed, to him, romantic but unlikely. Jesse believed that if anything was going to kill him it would be his brain. A tumour, an aneurysm, a sudden unexplained blow to the back of the head.

Whenever his mother or the family paediatrician intervened – promising that he was healthy and unlikely to die – he would remember the sight of his sister’s green eyes flying open in that humid hospital room just after the doctors had told his parents there was nothing more they could do.

Jesse sat in class, tapping his fingers and imagining the build-up of intracranial pressure. His anxious, overactive brain swelling like a sponge against the cage of his skull. By the time his family left Indonesia and returned to London, life was like a fickle lover, leaving him guessing and sick and wanting more time.

A few more years was not enough. He might never go to Argentina, never have sex, never ride in an open-top convertible along the California coastline with the wind in his hair and shadows at his back. All these things had never been his and yet he felt as if they’d been taken from him. The future, the freedom to hope for it.

His suffering – made ineffably worse by the fact that no one believed him – grew so bad that by age thirteen he was a morbid recluse. He spun away from his classmates like a satellite in a doomed orbit. Lay in bed, tallying all the time he had already lost, too tired to get up, to cut his nails, to get dressed. His older sister would stand over his bed in her crumpled school uniform and shout, ‘Some people have real problems, you know.’

But when applications to the Off-World Colonization Project opened up, Jesse saw his salvation.

Like most people his age, he had grown up with dreams of Terra-Two. Built papier-mâché models of the habitable exoplanet in kindergarten. He had been seven or eight when the Search for Life on Terra-Two had started, with unmanned satellites landing on alien shores and sending back images of the verdant earth, clean-water lakes, a thriving ecosystem and no humans. By the end of the twentieth century, many countries had mastered interplanetary travel and set their sights on neighbouring stars. When the grainy footage of this new and beautiful planet was broadcast across the globe, Terra-Two ignited the imagination of every child Jesse’s age.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)