"You've sinned, brother Yefimych," said the Cossack captain. "So there's nothing you can do but give yourself up!"

"I won't!" replied the Cossack.

"You should fear God's anger! You are not a heathen Chechen, you're an honest Christian. You've gone astray and it can't be helped. You can't escape your fate!"

"I won't give myself up!" the Cossack shouted menacingly, and we could hear the click of the pistol as he cocked it.

"Hey, missus!" the Cossack captain said to the old woman. "You speak to your son-maybe he'll listen to you... After all, this sort of thing is only defying God. Look, the gentlemen have been waiting for two hours now."

The old woman looked at him intently and shook her head.

"Vasiliy Petrovich," said the Cossack captain, walking over to the major, "he won't give himself up-I know him. And if we break in the door, he'll kill many of our men. Wouldn't it be better if you ordered him to be shot? There is a wide crack in the shutter."

At that moment, a strange thought flashed through my mind; like Vulić, I thought of putting fate to a test.

"Wait," I said to the major, "I'll take him alive." Telling the Cossack captain to keep him talking and stationing three Cossacks at the entrance with instructions to break in the door and to rush to help me as soon as the signal was given, I walked around the hut and approached the fateful window, my heart pounding.

"Hey there, you donkey!" shouted the Cossack captain. "Are you making fun of us or what? Or maybe you think we won't be able to capture you?" He began hammering at the door with all his strength, while I, pressing my eye to the hole, followed the movements of the Cossack inside, who did not expect an attack from this side. Then I suddenly broke off the shutter and threw myself through the window, head first. The pistol went off next to my ear and the bullet tore off an epaulet. The smoke that filled the room, however, prevented my adversary from finding his saber, which lay beside him. I hugged him in my arms – the Cossacks broke in, and in less than three minutes the criminal was tied up and led off under guard. The people left for home and the officers congratulated me-and indeed they had reason to do so.

After all this, one might think, how could one help becoming a fatalist? But who knows for certain whether he is convinced of anything or not? And how often we mistake a deception of the senses or an error of reason for conviction!

I prefer to doubt everything. Such a disposition does not preclude a resolute character. On the contrary, as far as I am concerned, I always advance more boldly when I don't know what is waiting me for me. After all, nothing worse than death can happen-and death you can't escape!

After returning to the fort, I told Maksim Maksimich everything I had seen and experienced, and wanted to hear his opinion about predestination. At first he didn't understand the word, but I explained it to him as best I could, whereupon he said, wisely shaking his head: "Yes, sir! It's a funny business that! By the way, these Asiatic pistol cocks often miss fire if they are poorly oiled, or if you don't press hard enough with your finger. I must admit I don't like those Circassian rifles either. They are a bit inconvenient for the likes of us-the butt is so small that unless you watch out you can get your nose scorched... Their sabers, now, are a different matter-I take my cap off to them!"

Then he added after thinking a little more: "Yes, I'm sorry for that poor man... Why the hell did he stop to talk to a drunk at night! I suppose, though, that all that happened to him was already written in that big book [113] we've added "big book" here – it's our predestined fate, the mythical story that the author God has already assigned every detail to our mortal lives, and supposedly written it in a book available for consultation in heaven. Note the parallel to a similar expression at the start of this novel.

when he was born!"

I could get nothing more out of him. In general he doesn't like metaphysical talk.

1837-9 [114] Another online edition of this work can be found at the University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center . That English translation, entitled "The Heart of a Russian," by J. H. Wisdom Marr Murray, N.Y.: Knopf, 1916, has a different order to the chapters and has heavy Victorian prose and sketchy footnotes. However, the edition, by Judy Boss, Carolyn Fay, and David Seaman, does have page numbers and a few color illustrations. We did not refer to it when doing this edition. A text-only version of that translation was released in Project Gutenberg in May, 1997. For further references, please see the books by Cornwell and Nabokov previously cited, as they contain notes, a map, chronologies, excerpts from critical material, and everything you need.

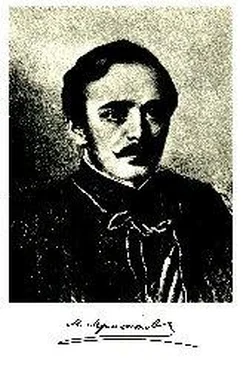

(accent on first syllable) was a great poet and not a bad landscape painter either. He was exiled to the front line of the colonial war that the Russians carried on against the Caucasian tribesmen in the first part of the 19th century – twice. He had visited the area as a boy a couple of times. After attending Moscow University and graduating from military school he became friends with some of those who played a part in the failed Decembrist uprising. He greatly admired the Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin and was upset by his death in a duel in January 1837, so he wrote a eulogy – that caused his first political exile. There he fought bravely, studied and translated some Caucasian literature, and met some revolutionary exiles. As well as doing some painting he picked up the ideas for this book and some great poems. After his return to Moscow, he again got into trouble and was exiled to the Caucasus a second time. He was killed in a duel, much like the one in this book, at the age of 26. Nabokov translates a wonderful recursive poem he wrote just before that duel.The reported reaction by Czar Nicholas I was "a dog's death for a dog."

Lermontov's title in manuscript was One of the Heroes of the Beginning of the Century, although the book as printed is supposed to take place starting in the fall of 1837. In English, the novel has been variously entitled A Hero of our Own Time, The Hero of Our Days, A Hero of Our Times, and The Heart of a Russian. We employ the most common and traditional title.

Written 1837 to 1839, the book was first printed April 1840, after three of the chapters had been published as stories in a magazine. The preface was added for the second edition, 1841 – it was at that time printed at the beginning of volume (part) 2. (Some translations put the preface at the end of the book.) This book comes at the end of the Romantic period and many critics feel it makes a transition to Realism. Some point out its striking modern aspects of existential irony and innovative narrative discourse.

We also referred to but did not literally copy from the interpretation in the 1958 translation by Vladimir and Dmitri Nabokov, Doubleday Anchor Books. (We draw attention especially to the authoritative introduction and notes of this book, even though they did not have access to the early editions – and the Edward Gorey cover hits the nail on the head for modern readers.) Referred to hereafter as "Nabokov."

how to interpret the irony in this book is the subject of a raft of books and articles listed in the Everyman edition, ranging from early Russian critics to Soviet Marxist-Leninist to Formalist to modernist and post-modernist and psychoanalytic. But why not just read the book here and decide for yourself?

slang American term for rural, provincial, i.e., not St. Petersburg or Moscow.

Читать дальше

![Михаил Лермонтов - A Hero of Our Time [New Translation]](/books/27671/mihail-lermontov-a-hero-of-our-time-new-translati-thumb.webp)