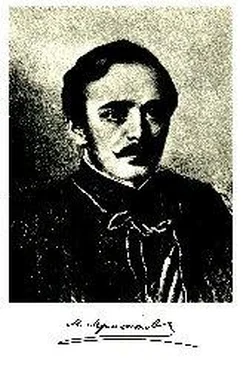

A Hero of Our Time

By Mikhail Lermontov

The Author's Preface (to the 2nd edition)

Bela

Maksim Maksimich

Introduction to Pechorin's Journal

Taman

Princess Mary

The Fatalist

[Notes]

The preface is the first and at the same time the last thing in any book. It serves either to explain the purpose of the work or to defend the author from his critics. Ordinarily, however, readers are concerned with neither the moral nor the journalistic attacks on the author – as a result they don't read prefaces. Well, that's too bad, especially in our country. Our public is still so immature and simple-hearted that it doesn't understand a fable unless it finds the moral at the end. It fails to grasp a joke or sense an irony [5] how to interpret the irony in this book is the subject of a raft of books and articles listed in the Everyman edition, ranging from early Russian critics to Soviet Marxist-Leninist to Formalist to modernist and post-modernist and psychoanalytic. But why not just read the book here and decide for yourself?

– it simply hasn't been brought up properly. It's as yet unaware that obvious violent abuse has no place in respectable society and respectable books, that education nowadays has worked out a sharper, almost invisible, but nevertheless deadly weapon, which behind the curtain of flattery cuts with a stab against which there is no defense. Our public is like the person from the sticks [6] slang American term for rural, provincial, i.e., not St. Petersburg or Moscow.

who, overhearing a conversation between two diplomats belonging to hostile courts, becomes convinced that each is being false to his government for the sake of a tender mutual friendship.

This book recently had the misfortune of being taken literally by some readers and even some reviewers. Some were seriously shocked at being given a man as amoral as the Hero of Our Time for a model. Others delicately hinted that the author had drawn portraits of himself and his acquaintances... What an old, weak joke! But apparently Russia is made up so that however she may progress in every other respect, she is unable to get rid of foolish ideas like this. With us the most fantastic of fairy tales has hardly a chance of escaping criticism as an attempt to hurt our feelings!

A Hero of Our Time, my dear readers, is indeed a portrait, but not of one man. It is a portrait built up of all our generation's [7] actually, the Romantic excesses were incurred by the generation that was just ending, with the Byronic hero as the exemplar, while Lermontov's contemporaries such as those portrayed by Turgenev and Dostoeyevsky went on to new vices and virtues. However, the personality of this type of hero or criminal has fascinated a lot of writers and even readers of detective or spy novels in many cultures.

vices in full bloom. you will again tell me that a human being cannot be so wicked, and I will reply that if you can believe in the existence of all the villains of tragedy and romance, why wouldn't believe that there was a Pechorin [8] the name is derived from that of a Siberian river, as is Onegin by Pushkin. Of course, there are endless speculations about the character of Pechorin. What do you think? Have you known anyone like him?

? if you could admire far more terrifying and repulsive types, why aren't you more merciful to this character, even if it is fictitious? Isn't it because there's more truth in it than you might wish?

You say that morality will gain nothing by it. Excuse me. People have been fed so much candy they are sick to their stomachs. Now bitter medicine and acid truths are needed. But don't ever think that the author of this book was ever ambitious enough to dream about reforming human vices. May God preserve him from such foolishness! It simply amused him to picture the modern man as he sees him and as he so often-to his own and your own misfortune-has found him to be. It's enough that the disease has been diagnosed – how to cure it only the Lord knows!

Part I [9] the division into parts this way makes no sense (Nabokov called it "purely fortuitous") and seems to have been an invention of the clumsy editor of the second edition. Russian literature did not yet have a tradition of the prose novel, while European printers at the time usually divided novels into separate volumes for convenience and sales. If one wanted to read the book in chronological order of the fictional events, it would be this way: Taman, Princess Mary, Bela (The Fatalist comes in the middle of this), Maksim Maksimich, and the Preface. However, the order Lermontov uses does spiral in on Pechorin's character effectively. By the way, there are references in the book to "a long chain of tales" and teases about "a fat notebook" of remaining material, but, sorry, this is all we've got.

I was traveling along the military road [10] The Georgian (and Ossetian) north-south military highways built by the Russians over the middle part of the Caucasus Mountains are still the main routes. The track from Tibilisi (Tiflis) to Vladikavkaz follows the Aragva River, over the 8,000-ft. Pass of the Cross, the Koyshaur Canyon, and down through Kazbek and Lars along the Terek River, which flows to the Caspian Sea. The road is more than 120 miles long. The area is called "Asiatic" by European Russians.

back from Tiflis [11] now called T'bilisi, capital of the now independent nation of Georgia. Georgia has had a long relationship with Russia, notably between the Treaty of Georgievsk, 1783, and 1878, when the Russians drove to the Black Sea in a war against the Turks. In 1837 Georgia was peacefully run by the Russians. However, the mountain people to the north were involved in bitter resistance to the Russian takeover of their territory, and political rebels were sent to this front by the Czar's government just as they were to Siberia.

. the only luggage in the little cart [12] telezhka , crude springless horse-drawn carriage.

was one small suitcase half full of travel notes about Georgia. Fortunately for you most of them have been lost since then, though luckily for me the case and the rest of the things in it have survived.

The sun was already slipping behind a snow-capped ridge when I drove into Koishaur Valley. The Ossetian coachman, singing at the top of his voice, tirelessly urged his horses on in order to reach the summit of Koishaur Mountain before nightfall. What a glorious spot this valley is! All around it tower awesome mountains, reddish crags draped with hanging ivy and crowned with clusters of plane trees, yellow cliffs grooved by torrents, with a gilded fringe of snow high above, while down below the Aragva River embraces a nameless stream that noisily bursts forth from a black, gloom-filled gorge and then stretches in a silvery ribbon into the distance, its surface shimmering like the scaly back of a snake.

On reaching the foot of the Koishaur Mountain we stopped outside a tavern where some twenty Georgians and mountaineers made up a noisy assembly. Nearby a camel caravan had halted for the night. I saw I would need oxen to haul my carriage to the top of the confounded mountain, for it was already fall and a thin layer of ice covered the ground, and the climb was a mile and a half long.

So I had no choice but to rent six oxen and several Ossetians. One of them lifted up my suitcase and the others started helping the oxen along-though they did little more than shout.

Behind my carriage came another pulled by four oxen with no visible effort, though the vehicle was piled high with baggage. This rather surprised me. In the wake of the carriage walked its owner, puffing at a small silver-inlaid Kabardian [13] people (Cherkes) in the northwest Caucasus Mountains (Abkhazia, Kabardia) fought the Russians from 1815 to about 1839, when they were mostly subdued. In 1864 the entire nation of about 400,000 people emigrated to Ottoman territory rather than live under the Russians. They have an ancient origin evidently absorbing Greek, Roman and possibly Crusader elements, and because they were tall, handsome, and intelligent were favored slaves, mercenaries, and managers.

Читать дальше

![Михаил Лермонтов - A Hero of Our Time [New Translation]](/books/27671/mihail-lermontov-a-hero-of-our-time-new-translati-thumb.webp)