MIKHAIL BULGAKOV - THE WHITE GUARD

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «MIKHAIL BULGAKOV - THE WHITE GUARD» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Русская классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:THE WHITE GUARD

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

THE WHITE GUARD: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «THE WHITE GUARD»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Copyright © 1971 by McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 70-140252 08844

Printed in Great Britain

THE WHITE GUARD — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «THE WHITE GUARD», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What about the Turbins? Where did they live? Until this year (to be precise, until April of this year, when I read The White Guard again for the second time in thirty years), I only remembered that they lived on St Alexei's Hill. There is no such street in Kiev, but there is a St Andrew's Hill. For some reason known only to Bulgakov, he, the author, having kept the real names of all the other streets and parks in Kiev, changed the names of the two streets most intimately linked with the Turbins themselves: he changed St Andrew's to St Alexei's Hill, and he changed Malo-Podvalnaya (where Julia saves the wounded Alexei) to Malo-Provalnaya Street. Why he did this remains a mystery, but it was nevertheless not very difficult to deduce that the Turbins lived on St Andrew's Hill. I also remembered that they lived near the bottom of the hill in a two-storey house, on the second floor, whilst Vasilisa their landlord lived on the first floor. That was all I remembered.

St Andrew's Hill is one of the most typically 'Kievan' streets in the city. Very steep, paved with cobblestones (where else will you find them nowadays?), twisting in the shape of a big letter 'S', it runs down from the Old City to the lower part - Podol. At the top is the church of St Andrew - built by Rastrelli in the eighteenth Century - and at the bottom is Kontraktovaya Square (so-called after the fair - the 'Kontrakty' - that used to be held there in the spring; I can still remember the macerated apples, the freshly-baked wafer biscuits, the crowds of people). The whole street is lined with small, cosy houses, and only two or three large apartment houses. One of these I know well from my childhood. We called it 'Richard the Lionheart's Castle': a seven-storey neo-Gothic house built in yellow Kiev brick, with a sharp-pointed turret on one corner. It is visible from many distant parts of the city. If you pass under the rather oppressively low porte-cochere, you find yourself in a small stone-flagged courtyard which we, as children, found quite breathtaking. It was a place straight out of the Middle Ages. Vaulted Gothic arches, buttressed walls, stone staircases recessed into the thickness of the walls, suspended cast-iron walkways, huge balconies, crenellated parapets . . . All that was missing were the sentries, their halberds piled in a corner, and playing dice somewhere on an upturned cask. But that was not all. If you climb up the stone-built embrasured staircase you come out on to a hilltop, a glorious hilltop overgrown with wild acacia, a hilltop where there is such a view over Podol, the Dnieper and the countryside beyond the Dnieper that when you take people up there for the first time it is difficult to drag them away again. And below, clustered around the bottom of that steep hill are dozens of little houses, little backyards with sheds, with dovecots and strings of washing hung out to dry. I really don't know what's wrong with all the artists in Kiev: if I were them I would spend all my time up on that hill . . .

So that is what St Andrew's Hill is like. And it has not changed: there is not one new house in the whole street, it still has its big cobblestones, its wild acacia bushes and occasional gnarled American maples bending right out over the street; it was exactly like that ten, twenty, thirty years ago, and it was like that in the winter of 1918 when 'the City lived a strange unnatural life which is unlikely to be repeated in the twentieth century'.

Whereabouts on St Andrew's Hill did the Turbins live? I don't quite know why, but I convinced myself, and then I also started to convince my friends when I used to take them up on to that hilltop, that the Turbins lived in the little house next door to Richard the Lionheart's Castle. It had a verandah, a charming gateway in a high fence, a little garden and one of those twisted maples in front of the door. Of course they must have lived there! And that, as far as I was concerned, was where they had lived.

It turned out, however, that I was quite, quite wrong.

Now begins the most interesting part. What I have written so far has been, as it were, the prologue: I now come to the story proper.

It was 1965.

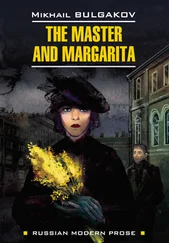

I need hardly describe the delight which we all experienced when Bulgakov's Theatrical Novel first appeared in print that year, 1and a year later The Master and Margarita? Twenty-five

1. Published in English translation in 1967 under the title Black Snow: A Theatrical Novel (London: Hodder and Stoughton; New York: Simon and Schuster).

2. Published in English in 1967 (London: Collins/Harvill; New York: Harper and P.ow).

years after the author's death came our first introduction to those hitherto unknown works of Bulgakov. And we were amazed and delighted, though this is not the place to enlarge on it. But I at least was even more amazed and delighted to find The White Guard again. Nothing in it had faded, nothing had aged, as if those forty years had never been. I found it difficult to tear myself away from the novel and I had to force myself to do so, in order to prolong the pleasure. Something like a miracle had happened before our eyes, something which happens very rarely in literature and which by no means every author can pull off - a book had been born again.

With the dramatised version of the story, The Days of the Turbins, this had not happened. No one found the post-war revival of the production at the Stanislavsky Theater particularly thrilling. Perhaps because after such actors as Khmelyov, Dobronravov and Kudryavtsev (to think that not one of them is still alive), after the original Lariosik played by Yanshin when he was young and thin, after Tarasova and Yelanskaya, it would have been extremely hard to mount a revival that said anything new. Perhaps, too, because not all works of art can be copied and it is none too easy to create something original. I await the new M.A.T. production with alarm (with hope, too, but with rather more alarm than hope). Shall I go and see it? I don't know. I'm afraid . . . afraid of so much: youthful memories, comparisons, parallels . . . Yes, I'm afraid for the Turbins, afraid for the play.

But the republished novel has completely disarmed me. It is as fresh and alive as when I first read it - not a wrinkle, not a gray hair. It has survived and conquered.

But I am getting carried away. To return to our topography: where did the Turbins live?

It transpires that the author made no secret of it. The exact address is given, literally on the second page of the novel: No. 13 St Alexei's Hill (for 'St Alexei's' read 'St Andrew's').

'For many years before her [their mother's] death, in the house at No. 13 St Alexei's Hill, little Elena, Alexei the eldest and baby Nikolka had grown up in the warmth of the tiled stove that burned in the dining-room.' Clear and precise. How was it that I didn't remember it? Somehow I just didn't.

So, to No. 13 St Andrew's Hill.

The really funny thing is that it turns out I even have a photograph of that house, although when I took it I had no idea of its significance or of its place in Russian literature. I had simply taken a liking to that little corner of Kiev (I used to be keen on photography and was particularly fond of certain parts of Kiev), and the vantage point from which I had taken the photograph, by climbing up to the top of one of Kiev's many hills, was extremely well chosen. St Andrew's Church, Richard the Lionheart's Castle, the hill, the gardens, the Dnieper in the background, and down below - the steep curve of St Andrew's Hill with the Turbins' house slap in the middle. Incidentally from the hill that I have just mentioned, the courtyard behind No. 13 can be clearly seen. It is most attractive, with its dovecot and its little balcony - I must have pointed it out hundreds of times to my friends when proudly showing them the charm and beauty of Kiev.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «THE WHITE GUARD»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «THE WHITE GUARD» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «THE WHITE GUARD» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.