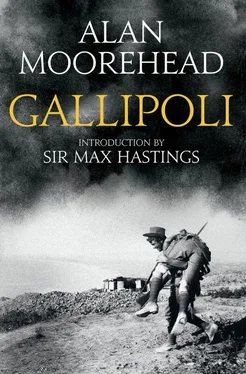

Then too very little information about the Gallipoli campaign reached the public during these early days. A full month went by before the Illustrated London News was able to publish photographs from the peninsula, and the official communiqués were not very helpful. From France a stream of soldiers, either wounded or on leave, returned to England, and their descriptions of the fighting in the trenches were in everybody’s mind. But Gallipoli was three thousand miles away and no soldier on leave ever got back as far as England, let alone Australia and New Zealand. To a great extent then it was left to the war correspondents to fill this gap.

Kitchener on principle was opposed to war correspondents, but he had, with some reluctance, permitted the English newspapers to send one man with the expedition, Mr. Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett. Ashmead-Bartlett was involved in difficulties from the moment of his arrival. Hamilton, though friendly, would allow him to send no messages until his own official cables had reached London, and this sometimes meant a delay of days. No criticism of the conduct of the operations was allowed by the censor. Nor could there be any indication of set-backs and delays. Ashmead-Bartlett’s lot seems really to have been a little too hard at times. He went ashore at Anzac Cove soon after the first assault wearing, for reasons best known to himself, a green hat, and was at once arrested as a spy. The Australians were about to shoot him when by chance a sailor whom he knew vouched for him. Soon afterwards he was nearly drowned when the ship in which he was travelling was torpedoed. The only other English correspondent at Gallipoli was a Renter man who was somewhat handicapped by being so short-sighted that he could only see a hundred yards.

Hamilton’s own despatches to Lord Kitchener tended at first to take an optimistic line. ‘Thanks to God who calmed the seas,’ he wrote on April 26, ‘and to the Royal Navy who rowed our fellows ashore as coolly as if at a regatta; thanks also to the dauntless spirit shown by all ranks of both Services, we have landed 29,000 upon six beaches in the face of desperate resistance.’ On April 27 he wrote again: ‘Thanks to the weather and the wonderfully fine spirit of our troops all continues to go well.’

Meanwhile a great deal had happened. On the night of the landing the destroyers on the Anzac front came in close and shone their searchlights on the cliffs to prevent the Turks from making a surprise raid in the darkness. Then in the morning the Queen Elizabeth and two other battleships each took a section of the enemy line and bombarded it so heavily that it seemed for a time that the hills were erupting like active volcanoes. Spotters went up in the kite balloons to a height whence they could see over the top of the peninsula, and with one lucky shot the Queen Elizabeth destroyed a freighter in the Narrows, seven miles away. The cruisers meanwhile came so near to the shore that the sailors could see the Turks running along the cliffs above, and the Turks in their turn sniped down on to the British officers standing on deck. There was very little the Turks could do to injure the warships, but they kept up an incessant artillery fire on the beach, and every boat that tried to reach the shore with stores and reinforcements was forced to run through a curtain of bursting shrapnel and machine-gun bullets. Under this barrage the Dominion soldiers fought out their battle for survival.

It was extremely savage fighting, for at this early stage neither side had any real idea of what they could or could not do, and consequently both commanders committed everything they had to the battle. Kemal was still convinced that he could drive the Allies into the sea before they had had time to dig in, and Birdwood was still determined to advance against him. Often the Turks charged directly into the Anzac line, and wild hand-to-hand fighting with the bayonet took place in the half-dug trenches. Three days of this went by before it became apparent to the opposing commanders that both their propositions were wrong: the Anzac soldiers could not be dislodged; equally they could not advance. Hardly a thousand square yards of territory had changed hands: and the bridgehead remained there, congested and confined, every part of it swept by fire from the heights above, but apparently immoveable. On the night of April 27, the fighting slackened, and both sides drew off to rest and gather their strength again.

Something of the same sort but on a wider front was happening at Cape Helles in the south. On the day after the landing the village of Sedd-el-Bahr fell, the scattered bridgeheads were joined together and the Turks drew back all along the line. Hamilton judged it to be absolutely vital to take Achi Baba before Liman von Sanders could bring reinforcements down to the toe of the peninsula, and on April 28, with the French on the right and the British on the left, a general forward movement began. It continued inland for a distance of about two miles against increasing opposition, and then came to a halt.

An extreme fatigue had now overtaken the soldiers. Many of them had been without sleep for two or even three nights, and their food, water and ammunition were running out. At Sedd-el-Bahr the River Clyde was firmly anchored to the shore, but the whole of the Allied position was under the fire of Turkish guns from across the straits and from the peninsula itself. The bulk of Hamilton’s forces was now on land, but the beaches still looked like the scene of a gigantic shipwreck with vast piles of stores and military equipment scattered about on every side, and until some order could be got out of this confusion — until the troops were rested and supplied — there was no possibility of renewing the advance. By April 28 all impetus was lost and the firing began to die away along the line.

Thus at the very outset the pattern of the Gallipoli campaign was established: the action, the reaction and the stalemate. The objective is set, the attempt is made, and it falls just short of success. Already Achi Baba had begun to dominate everybody’s mind. It loomed there on the skyline only a mile or two away, but as remote as Constantinople itself. It was not a spectacular hill in any way, for its height was only 709 feet and its sides sloped gently down to the Ægean through a pleasant countryside of olives and cypresses and scattered farms. But Hamilton was determined to take it. Once on the crest he believed that his guns would enfilade the straits as far as the Narrows, and the enemy line in the south would give way. On April 28 his position was particularly frustrating. He knew that time was running out. He saw the hill before him, and given another fresh division — perhaps even a brigade — he knew that he could have it. But there were no fresh divisions or brigades; everything he had was already committed to the battle, and for the time being the men were so worn out, so shocked and undermined by their casualties, that they could do no more. And so he returned to the questions which were destined to be endlessly repeated from this time onwards. Can he ask Kitchener for reinforcements? And even if Kitchener agrees to send them, will they arrive in time?

Even before the expedition had sailed there had been a misunderstanding about this matter of reinforcements. Kitchener’s attitude — and Hamilton was extremely conscious of it — seems to have been that he could spare so much and no more for Gallipoli, and Hamilton had better make the best of it. And so Hamilton’s modest requests had been rebuffed or had remained unanswered. Yet in the end Kitchener had relented. On April 6 he had sent a cable to Sir John Maxwell, the commander of the Egyptian garrison: ‘You should supply any troops in Egypt that can be spared or even selected officers or men that Sir Ian Hamilton may want for Gallipoli… This telegram should be communicated by you to Sir Ian Hamilton.’

Читать дальше