Gallipoli by John Masefield

Literary Thoughts Edition presents

Gallipoli,

by John Masefield

Transscribed and Published by Jacson Keating (editor)

For more titles of the Literary Thoughts edition, visit our website: www.literarythoughts.com

All rights reserved. No part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, copied in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise transmitted without written permission from the publisher. You must not circulate this book in any format. For permission to reproduce any one part of this edition, contact us on our website: www.literarythoughts.com.

This edition is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. It may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Amazon and purchase your own copy of the ISBN edition available below. Thank you for respecting the efforts of this edition.

Oliver said ... "I have seen the Saracens: the valley and the mountains are covered with them; and the lowlands and all the plains; great are the hosts of that strange people; we have here a very little company."

Roland answered ... "My heart is the bigger for that. Please God and His holiest angels, France shall never lose her name through me."

The Song of Roland.

A little while ago, during a short visit to America, I was often questioned about the Dardanelles Campaign. People asked me why that attempt had been made, why it had been made in that particular manner, why other courses had not been taken, why this had been done and that either neglected or forgotten, and whether a little more persistence, here or there, would not have given us the victory.

These questions were often followed by criticism of various kinds, some of it plainly suggested by our enemies, some of it shrewd, and some the honest opinion of men and women happily ignorant of modern war. I answered questions and criticism as best I could, but in the next town they were repeated to me, and in the town beyond reiterated, until I felt the need of a leaflet printed for distribution, giving my views of the matter.

Later, when there was leisure, I began to consider the Dardanelles Campaign, not as a tragedy, nor as a mistake, but as a great human effort, which came, more than once, very near to triumph, achieved the impossible many times, and failed, in the end, as many great deeds of arms have failed, from something which had nothing to do with arms nor with the men who bore them. That the effort failed is not against it; much that is most splendid in military history failed, many great things and noble men have failed. To myself, this failure is the second grand event of the war; the first was Belgium's answer to the German ultimatum.

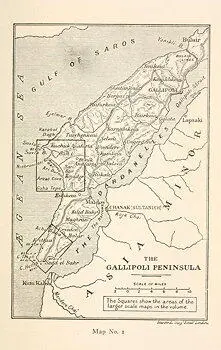

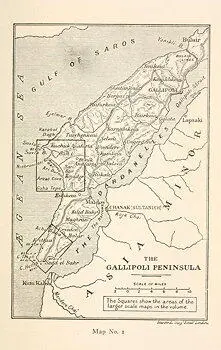

Map No. 1

The Peninsula of Gallipoli, or Thracian Chersonese, from its beginning in the Gulf of Xeros to its extremity at Cape Helles, is a tongue of hilly land about fifty-three miles long, between the Ægean Sea and the Straits of the Dardanelles. At its northeastern, Gulf of Xeros or European end it is four or five miles broad, then a little to the south of the town of Bulair, it narrows to three miles, in a contraction or neck which was fortified during the Crimean War by French and English soldiers. This fortification is known as the Lines of Bulair. Beyond these lines, to the southwest, the peninsula broadens in a westward direction, and attains its maximum breadth, of about twelve miles, some twenty-four miles from Bulair, between the two points of Cape Suvla, on the sea, and Cape Uzun, within the Straits. Beyond this broad part is a second contraction or neck, less than five miles across, and beyond this, pointing roughly west-southwesterly, is the final tongue or finger of the Peninsula, an isosceles triangle of land with a base of some seven miles, and two sides of thirteen miles each, converging in the blunt tip (perhaps a mile and a half across) between Cape Helles and Cape Tekke. There is no railway within the peninsula, but bad roads, possible for wheeled traffic, wind in the valleys, skirting the hills and linking up the principal villages. Most of the travelling and commerce of the peninsula is done by boat, along the Straits, between the little port of Maidos, near the Narrows, and the town of Gallipoli (the chief town) near the Sea of Marmora. From Gallipoli there is a fair road to Bulair and beyond. Some twenty other small towns or hamlets are scattered here and there in the well-watered valleys in the central broad portion of the Peninsula. The inhabitants are mostly small cultivators with olive and currant orchards, a few vineyards and patches of beans and grains; but not a hundredth part of the land is under cultivation.

The sea shore, like the Straits shore, is mainly steep-to, with abrupt sandy cliffs rising from the sea to a height of from one hundred to three hundred feet. At irregular and rare intervals these cliffs are broken by the ravines or gullies down which the autumnal and winter rains escape; at the sea mouth of these gullies are sometimes narrow strips of stony or sandy beach.

Viewed from the sea, the Peninsula is singularly beautiful. It rises and falls in gentle and stately hills between four hundred and eleven hundred feet high, the highest being at about the centre. In its colour (after the brief spring) in its gentle beauty, and the grace and austerity of its line, it resembles those parts of Cornwall to the north of Padstow from which one can see Brown Willie. Some Irish hills recall it. I know no American landscape like it.

In the brief spring the open ground is covered with flowers, but there is not much open ground; in the Cape Helles district it is mainly poor land growing heather and thyme; further north there is abundant scrub, low shrubs and brushwood, from two to four feet high, frequently very thick. The trees are mostly stunted firs, and very numerous in the south, where the fighting was, but more frequently north of Suvla. In one or two of the villages there are fruit trees; on some of the hills there are small clumps of pine. Viewed from the sea the Peninsula looks waterless and sun-smitten; the few water-courses are deep ravines showing no water. Outwardly, from a distance, it is a stately land of beautiful graceful hills rolling in suave yet austere lines and covered with a fleece of brushwood. In reality the suave and graceful hills are exceedingly steep, much broken and roughly indented with gullies, clefts and narrow irregular valleys. The soil is something between a sand and a marl, loose and apt to blow about in dry weather when not bound down by the roots of brushwood, but sticky when wet.

Those who look at the southwestern end of the Peninsula, between Cape Suvla and Cape Helles, will see three heights greater than the rolling wold or downland around them. Seven miles southeast from Cape Suvla is the great and beautiful peaked hill of Sari Bair, 970 feet high, very steep on its sea side and thickly fleeced with scrub. This hill commands the landing place at Suvla. Seven miles south from Sari Bair is the long dominating plateau of Kilid Bahr, which runs inland from the Straits, at heights varying between five and seven hundred feet, to within two miles of the sea. This plateau commands the Narrows of the Hellespont. Five miles further to the southwest and less than six miles from Cape Helles is the bare and lonely lump of Achi Baba, 590 feet high. This hill commands the landing place at Cape Helles. These hills and the ground commanded by them were the scenes of some of the noblest heroism which ever went far to atone for the infamy of war. Here the efforts of our men were made.

Читать дальше